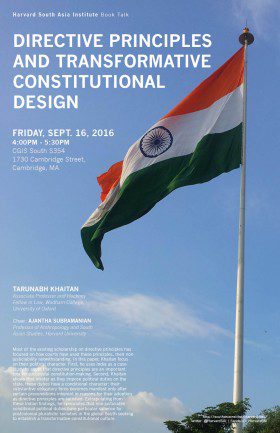

Book Talk

Tarunabh Khaitan, Associate Professor and Hackney Fellow in Law, Wadham College, University of Oxford

Chair: Ajantha Subramanian, Professor of Anthropology and South Asian Studies, Harvard University

Borrowing and developing the concept from Ireland, framers of India’s Constitution inserted a chapter titled ‘directive principles of state policy’ in the founding document. They were a mix of principles aimed at securing what they called an ‘economic democracy’, some guarantees we now call ‘social rights’ and some other curiosities like an exhortation for prohibition and a ban on cow slaughter. These were directed at the political organs of the state and made expressly non-justiciable. Despite being derided by scholars and lawyers as ‘mere pious wishes’ and ‘design flaws’, and (largely) rejected by post-Apartheid South Africa after due consideration, they have been adopted by at least 24 constitutions in Asia and Africa, including very recently by the latest Nepalese Constitution of 2015. India’s cultural influence on these jurisdictions, mostly in the global South, does not seem to provide sufficient explanation for their continued popularity with constitution makers.

Most of the existing scholarship on directive principles has focused on how courts have used these principles, their non-justiciability notwithstanding. In this paper, Khaitan focus on their political character. First, he uses India as a case-study to argue that directive principles are an important tool for successful constitution-making. He identifies the reasons why they became attractive to the framers of the Indian Constitution, and far from being mere pious wishes, they performed important and distinct political functions for the framers. Second, Khaitan shows that insofar as they impose political duties on the state, these duties have a conditional character: their substantive obligatory force becomes manifest only after certain preconditions inherent in reasons for their adoption as directive principles are satisfied. Extrapolating from these Indian findings, he speculates that non-justiciable conditional political duties have particular salience for postcolonial pluralistic societies in the global South seeking to establish a transformative constitutional culture.