The 2020–2021 Visiting Artist Fellowship Virtual Gallery

Welcome to the 2020–2021 Visiting Artist Fellowship Virtual Gallery

Our 2020-2021 Visiting Artist Fellowship cycle was reimagined to take place in the virtual world, inviting 13 Visiting Artist Fellows — including photographers, sculptors, videographers, and mixed media artists from India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal — to attend a series of online seminars curated to support their long-term art practice.

Below, you can view a virtual gallery of their artwork and learn more about each of their inspirations and insights into the world of art in South Asia.

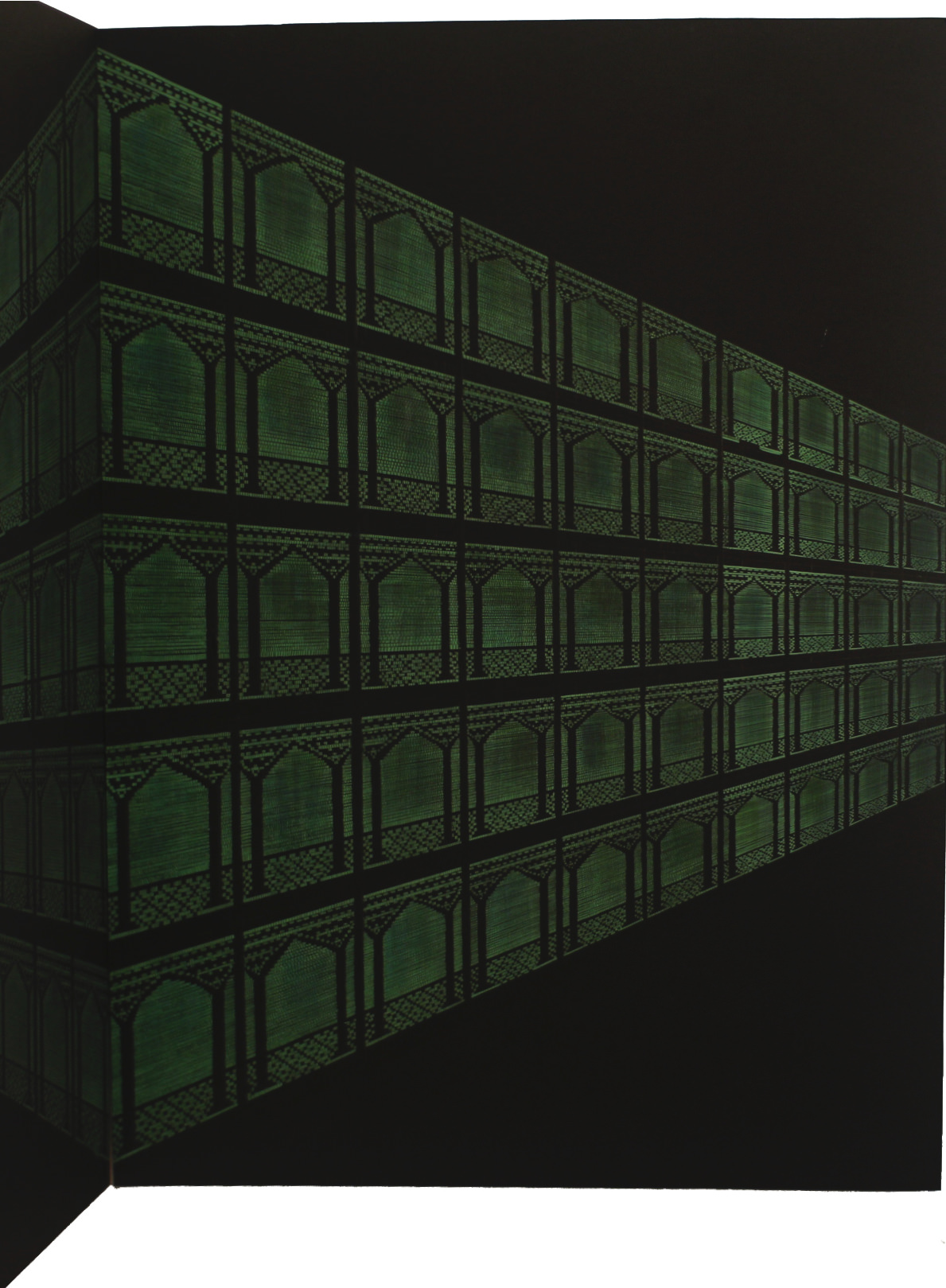

J A V A R I A A H M A D

PAKISTAN, MIXED MEDIA

Javaria Ahmad

Through her multidisciplinary art practice using ceramics as a major medium of her work, Javaria Ahmad explores the ambivalent relation of everyday utilitarian objects and practices with memories of constricted domesticity and womanhood in a patriarchal society. Storytelling and puns, often layered, pervade her work.

At a young age, numerous factors kickstarted my interest in art. My very first inspirations were my elder sister’s sketchbooks full of colored pencil cartoons and botanical drawings. Unfortunately, I was never allowed to touch them. I remember the feeling of unrelenting boredom in the monotonous school routine where art was the only class I enjoyed, and “playing house” with my cousins — spending entire afternoons making mud pots and engraving our imaginary houses in the earth. I’ll never forget the chalk drawings I used to make on my father’s steel cupboard, which I quickly erased before he entered the house every evening.

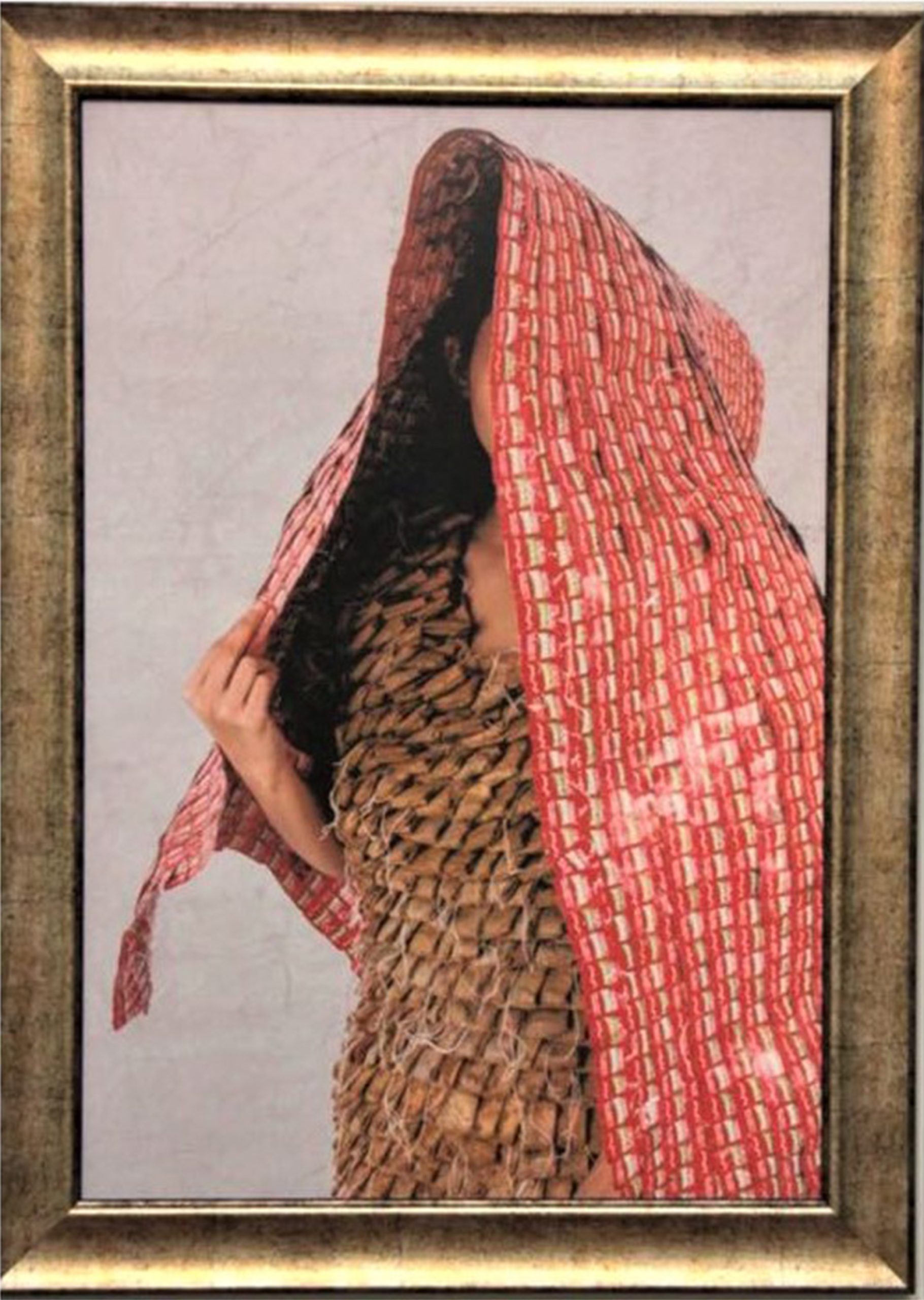

For you, a thousand times over

“This traditional wedding dress made out of used tea bags is a comment upon the match-making tea ceremony tradition. Unfortunately, many girls have to practice this tradition multiple times before finally getting approved for a marriage. Every tea a girl serves that gets rejected becomes demeaning baggage on her personality.”

You are more than a story

“The photograph of a girl wearing the wedding dress made of used tea bags comments upon the inglorious journey of a bride. The melancholy of this mirthless journey from match-making tea ceremony to marriage is felt only by the girl who has been through it.”

R I C H I B H A T I A

INDIA, PHOTOGRAPHY

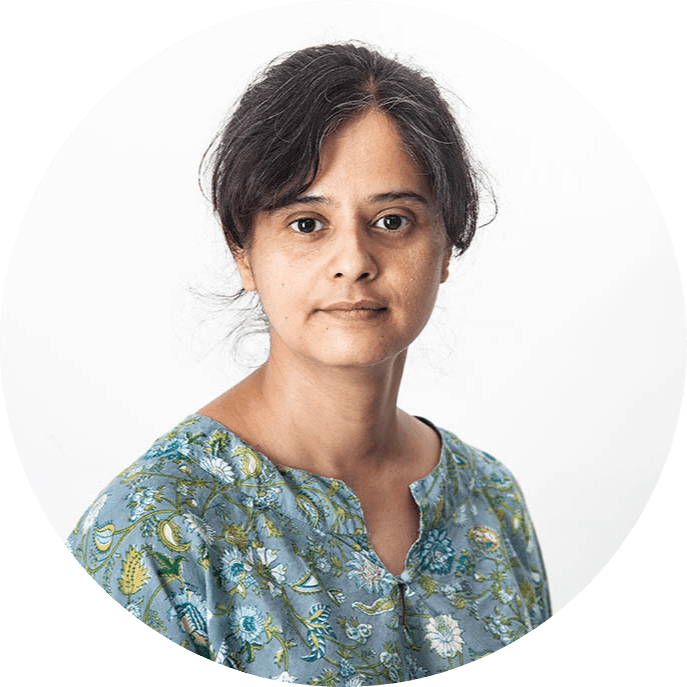

Richi Bhatia’s work traverses from extreme intuitive practices to prolonged processes. She creates an assemblage of metaphoric materials using fish scales, hair, and found laboratory equipment, to name a few, wherein they partially find root in an autobiographical context.

My works evolve in their form and approach during the process of making. As I create, I do not visualize in my mind the end result. The process is equally as important as the outcome, since every work evolves through an intuitive spirit deeply invested within my thoughts. My artwork addresses the similar ideas of body, identity, and personal history, and how they exist in a constant flux in relation to their surroundings.

Richi Bhatia

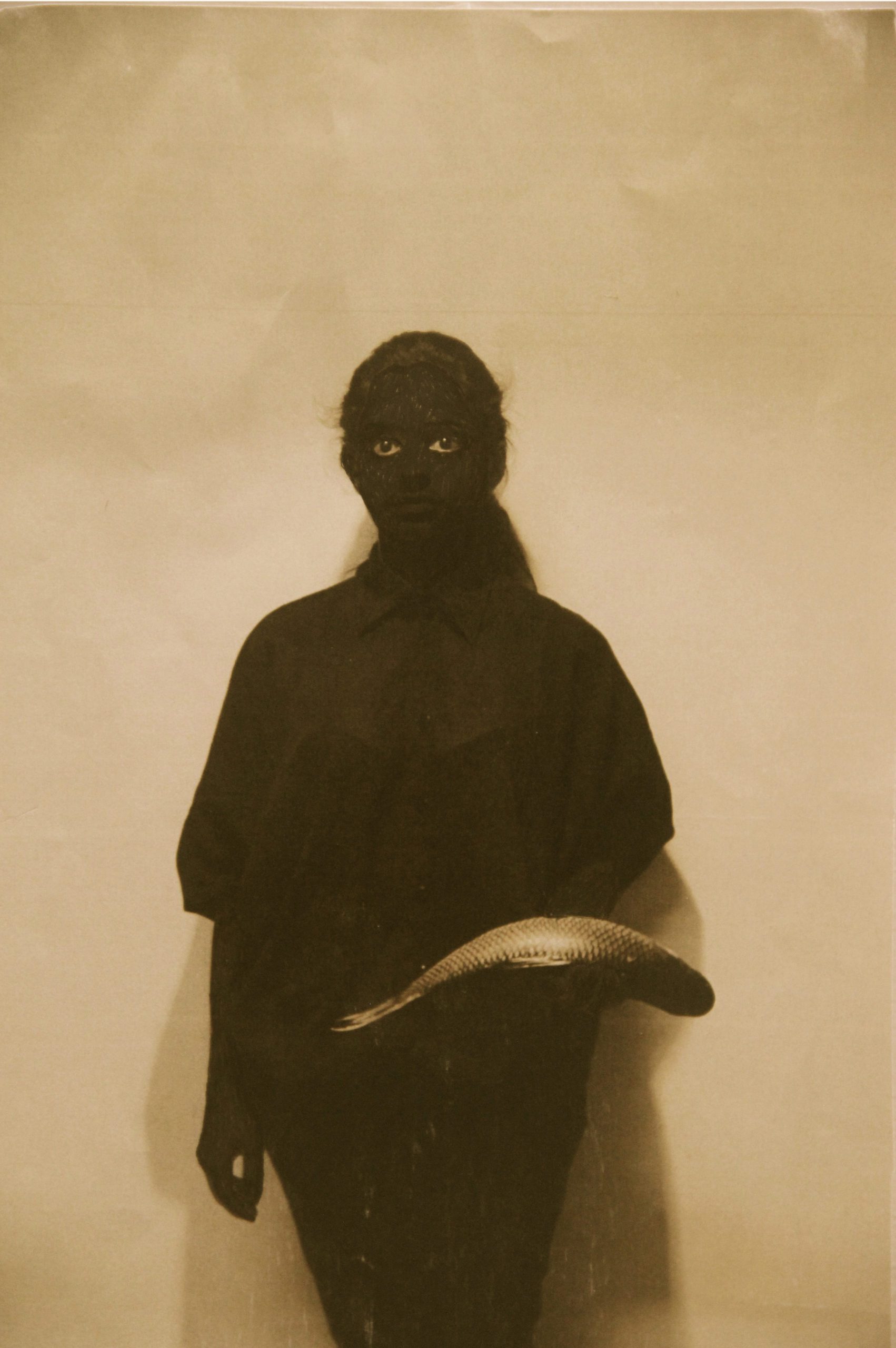

All good work is done the way ants do things little by little

“This work extensively explored the material of fish scales gathered from fishermen and fish sellers to serve as fictional material for some autobiographical concerns.”

Hamlet Without the Prince

“This work plays with the interpretations of gender politics and questions the notions and crises that gradually become synonymous to a person’s identity at large; for example: “The girl with curly hair” or “The girl with a skin disease.” Do these descriptions become the essence of a being?”

I S H I T A C H A K R A B O R T Y

INDIA, MIXED MEDIA

Ishita Chakraborty

Ishita Chakraborty’s practice reveals through inkless drawings, installations, poetry, video, and sound, tracing the stories of migration, the traumas of colonialism, and the understanding of language and identity.

Sometimes, in my childhood, I traveled to historical sites with my parents. I remember the names and words engraved by former visitors on walls and pillars. I find this technique of preserving memory interesting and provocative. This concept helped me to develop my own method of registering other people’s voices and memories by scratching on paper. The rigorously hand-scratched drawings depict collected memories of home and exile, communicating floor plans, folktales, poetries, musical scores, maps, landscapes, and transient geographies crossing Asia and Europe.

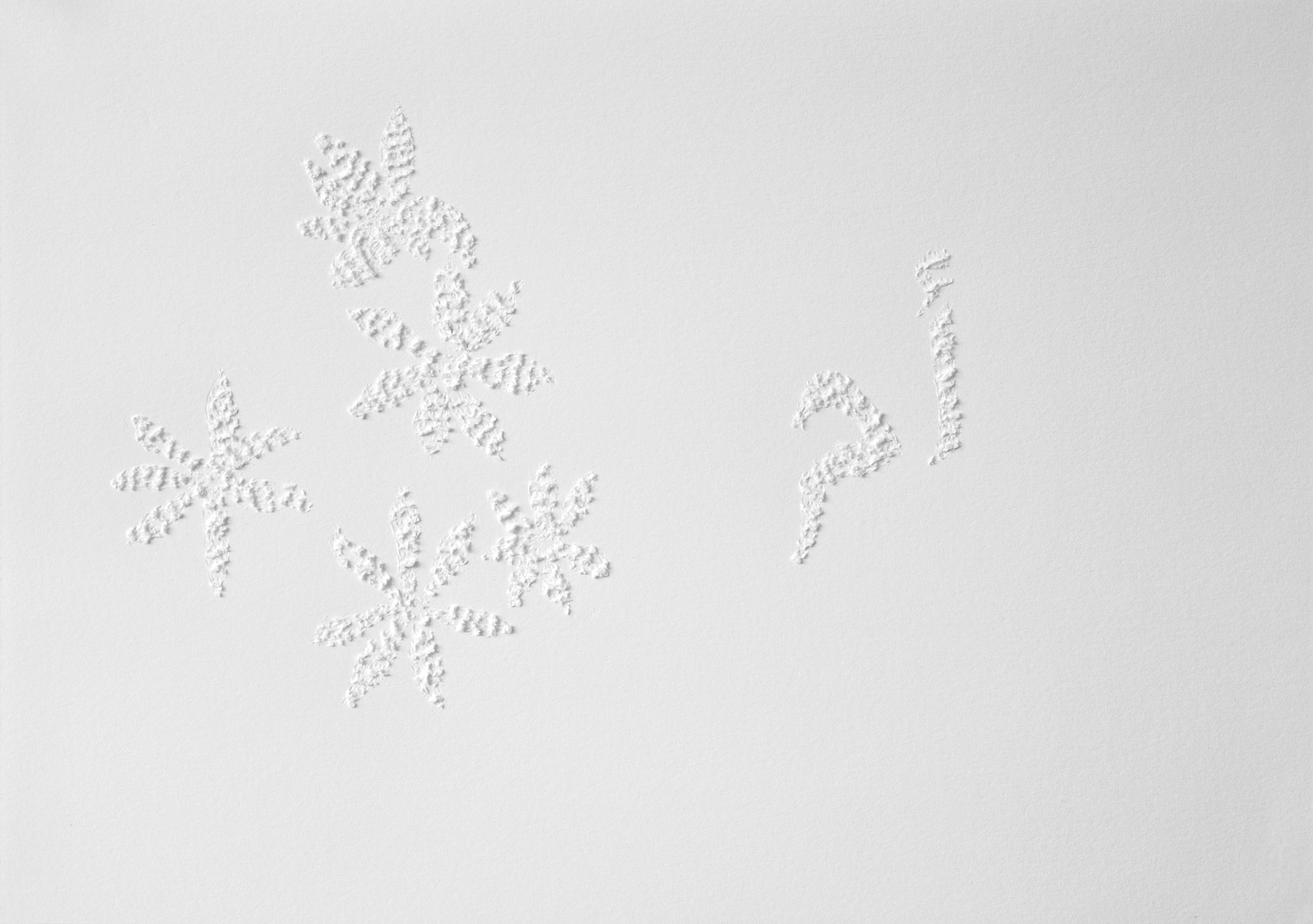

Zwischen I Between

“أم means “mother” in Arabic. I met a Syrian national who left his country due to war and took refuge in Europe as an asylum seeker. He can no longer return home. He spoke about his mother and her jasmine flowers. I tried to preserve the scent of his mother’s jasmine garden and his homesickness.”

Mute Tongue

“How are the stories of refugees narrated in the news? Who speaks about their plight? Often, the marginalized voices of refugees are unheard or ignored. In this work, I wrote a poem based on two stories I listened to of refugees from Somalia and Sri Lanka, and converted the audio file into an audio graph and cast it in porcelain.”

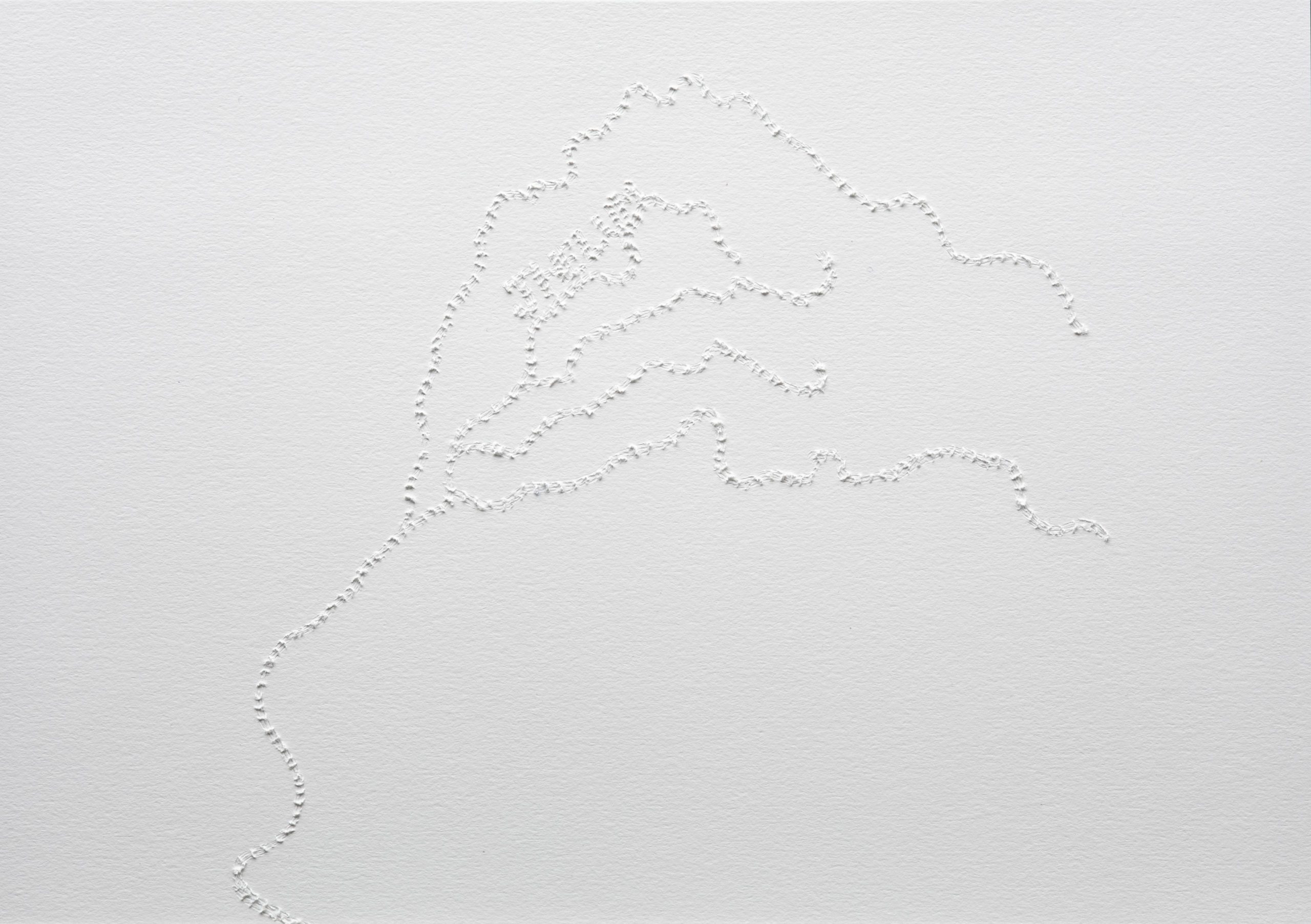

Zwischen I Between

“In recent times, I met a group of Pakistani and Afghani refugees in Switzerland, and every time we meet we talk about home, common recipes, rivers, and landscapes. I inscribed our exilic longings into the beloved river Jhelum flowing into the paper without any geographic territories and conflicts.”

S U D I P T A D A S

INDIA, INSTALLATION

Sudipta Das is a mixed media visual artist who explores poignant narratives through the unconventional use of paper. Her practice focuses on the idea of bearing witness and the importance of intimate socio-political issues, the realities of climate change, and human migration.

As I piece together used and unused paper, fragments of lost and previous identities are forged into newfound ones. A quest for identity gathers a whirlpool of belongings, feelings, memories, and expressions into fragile yet resilient paper sculptures. Thus, paper becomes a metaphor for the constant flux of the human spirit. It brings about a sense of belonging that so many people seek, through photographs, certificates, identity papers, archives, documents, and records. What are we, really, without these “paper personalities”? How has paper come to dictate who we are and where we belong?

Sudipta Das

Shelter

“This series portrays how displaced people live. It exhibits hutments, temporary tenements made of plastic, cloth or corrugated boards, with clothes hanging on a line. Even in these decrepit covers and temporary shelters, people have created their own works and secure spaces that celebrate the joys of everyday living.”

A Soaring to Nowhere

“This installation is an attempt to express the emotional and disoriented state of refugees, and stresses the non-existence and displacement of refugees through the figures suspended mid-air. They seek direction, but have nowhere to go.”

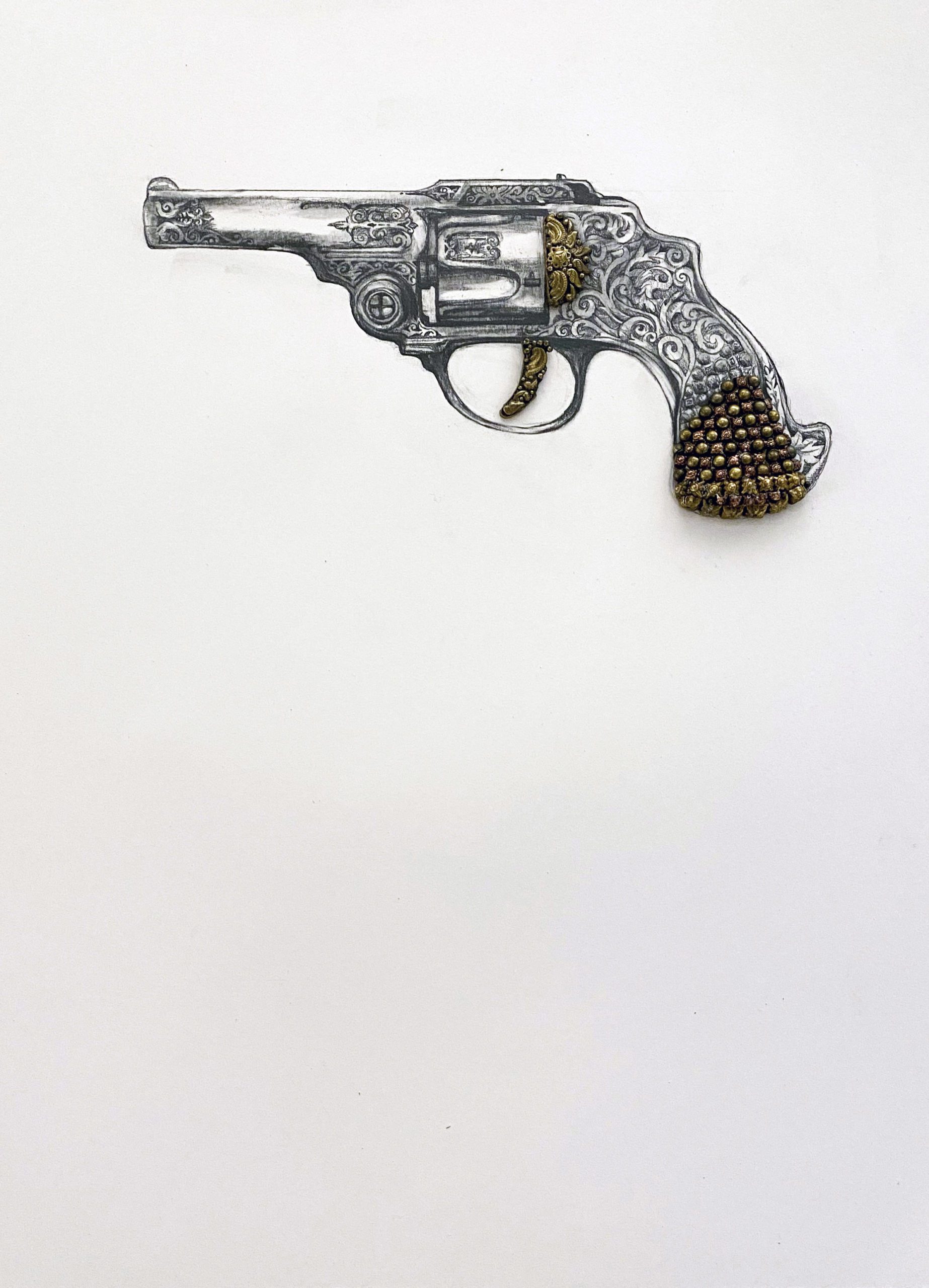

P R O M O T E S H D A S P U L A K

BANGLADESH, INSTALLATION

Promotesh Das Pulak

Promotesh Das Pulak was trained as a painter. The use of diverse material has played a pivotal role in his artistic practice, simultaneously permeating through media such as sculpture, video, image manipulation, photography, and installation. He is fascinated with the aesthetics of violence and its combination with the beauty that reflects the visibility of socio-political unrest around the world.

I find the embellishments on weapons captivating, yet I am conflicted by the aesthetic of artistic details in combination with the lethality of the weapons. With modernity, the instrument of death has been embellished with designs, signifying a status, power, might, and richness.

Untitled (Beautiful Way to Die) 3

“This drawing series began in 2019, highlighting different ancient war weapons. Through these works I explore the duality that exists between the beautiful floral ornamentation in contrast with the deadly sharp structure of copper swords, arrows, daggers, and pistols.”

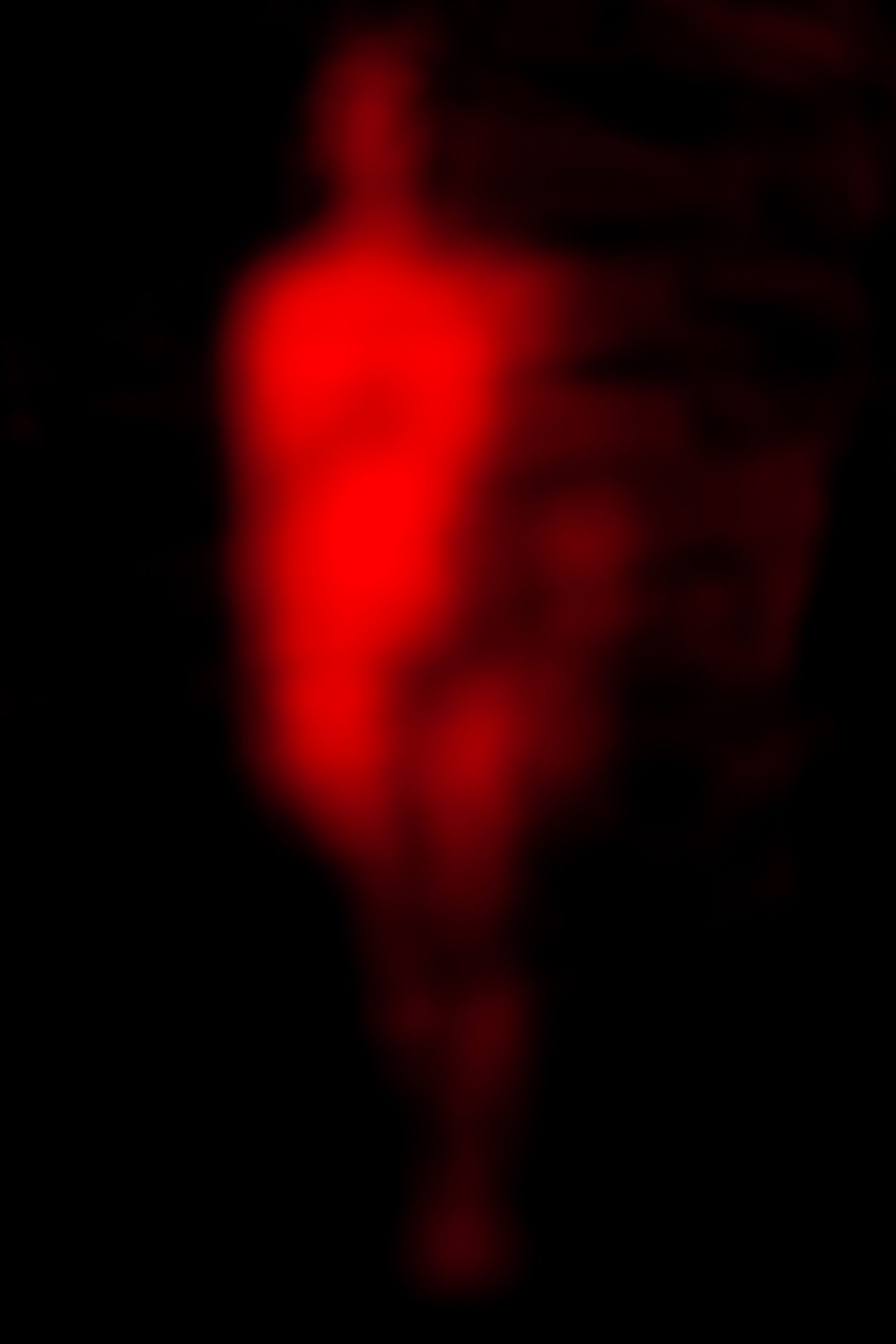

B U N U D H U N G H A N A

NEPAL, PHOTOGRAPHY

Bunu Dhungana uses photography as a medium to explore and question the world around her. While her personal projects center around gender, she has worked in a wide range of forms — from visual ethnography and NGO/INGO work to commercial and journalistic work. Dhungana believes that visual stories can reach out to people, engage them, and start conversations.

It took me many years to find myself in the photography medium. One of the things that has inspired my work is the constant societal reminder that I am a woman, and that I have to behave in a certain manner. From the way you sit, eat, dress, talk, and laugh — everything is scripted; the do’s and don’ts are clearly laid out. I have always hated this. What happens if women like me don’t fit into the story that has already been created for them? I started using photography as a way to express my suffocation under these expectations.

Bunu Dhungana

Confrontations

“A Nepali woman’s experience of life is shaped by patriarchy. Non-conformity comes at a cost: any defiance of norms raises questions, suspicion, concern, ridicule — some visible, others silent and invisible. I am made aware regularly that I keep crossing many such boundaries.”

Confrontations

“The use of the color red in my artwork has helped me to explore what it means to be a woman in my society. The work has changed from a personal exploration to a commentary on the society I live in, where women are expected to keep their lives under wraps.”

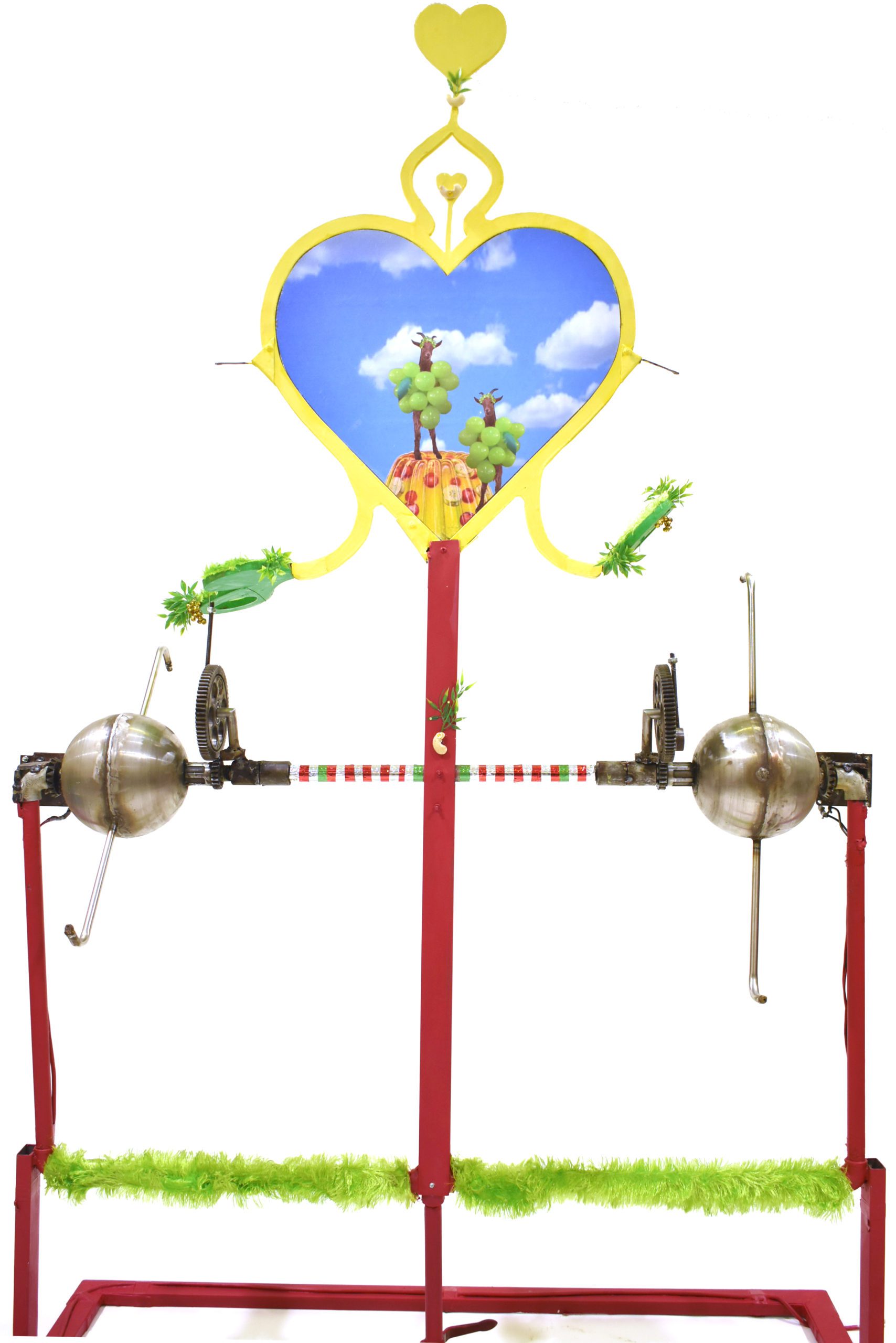

A M M A R A J A B B A R

PAKISTAN, SOUND INSTALLATIONS

Ammara Jabbar

Ammara Jabbar is a multidisciplinary artist from Karachi, Pakistan. Her work explores the domestic and performative as a means to investigate notions of gender and public space in the city, imagining new radical futures of belonging for all groups.

My work actively takes on a vernacular aesthetic — an exercise in excess, like the bride who sits ceremonially in ornate grandeur. Locating the kitsch and examining social class and aesthetics, I hope to deviate from the visuals present within Western art and ground my expression within my perception of visual culture in Pakistan.

Chop Me a Tune, Silly

“The work is a performative sculpture where the blender has been reimagined as a musical instrument. It comments on the objects given as gifts to the bride as a gesture to start her new life; a cordial assemblage of toilet plungers to giant food processors; all piquantly centering the female as a facilitator of housework.”

Sweetness Died VIP

“The moving mechanism was based on Heron’s steam engine, the first instance of steam-powered movement. The pragmatic potential of it wasn’t recognized at the time, thus delaying the Industrial Revolution. It was resigned as a theatrical apparatus to entice temple worshippers.”

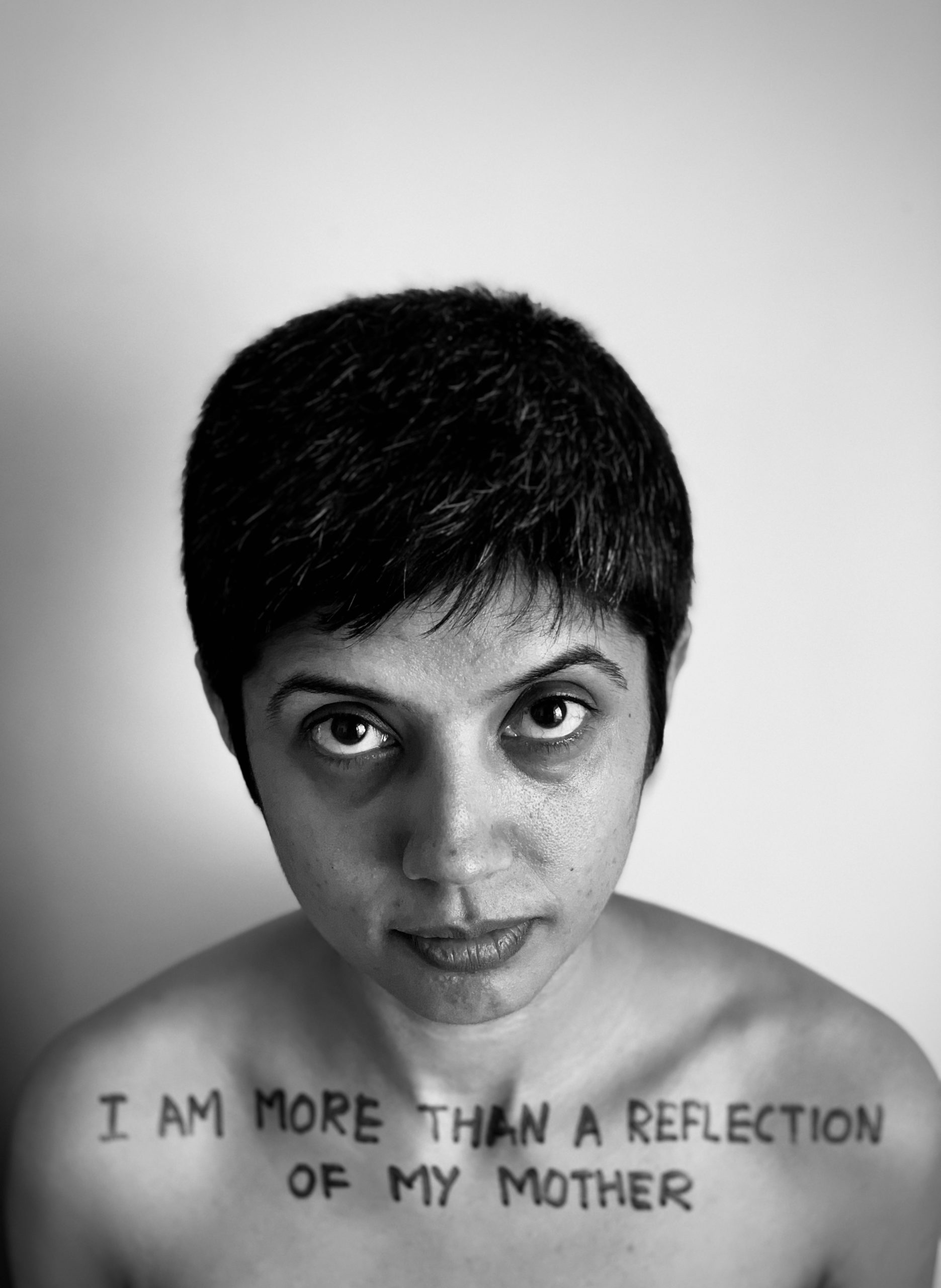

P R A G A T I D A L V I J A I N

INDIA, PHOTOGRAPHY AND VIDEO

Pragati Jain’s work draws attention to prevailing conflicts in civilized societies, where each one of us has similar aspirations, struggles, and persistent ideas of practicing equality. In an atmosphere of shared fear, confusion, and hope, she creates art about the likenesses that bind us.

Alongside my journey as an artist, I was experiencing the pressure of being an ambitious woman, as an outsider in a civilized society that was still held by conservative axioms. My travels through Indian cities crowded with men made me feel vulnerable. I needed to feel safe and independent. There was a desperate search for identity and a struggle to find my place in society, which came to influence most of my work.

Pragati Dalvi Jain

Navneet

From the series “I am more than a reflection of my mother”

“The aspiration to raise her child as an individual beyond her perception and constraints, beyond her own inhibitions, subsists in every mother at various levels. Navneet is a mother herself, and wants her 5-year-old son to grow up without biases. She had to unlearn a lot from her childhood conditioning and the world she grew up in. She wishes her son to be empathetic, rather than judgmental.”

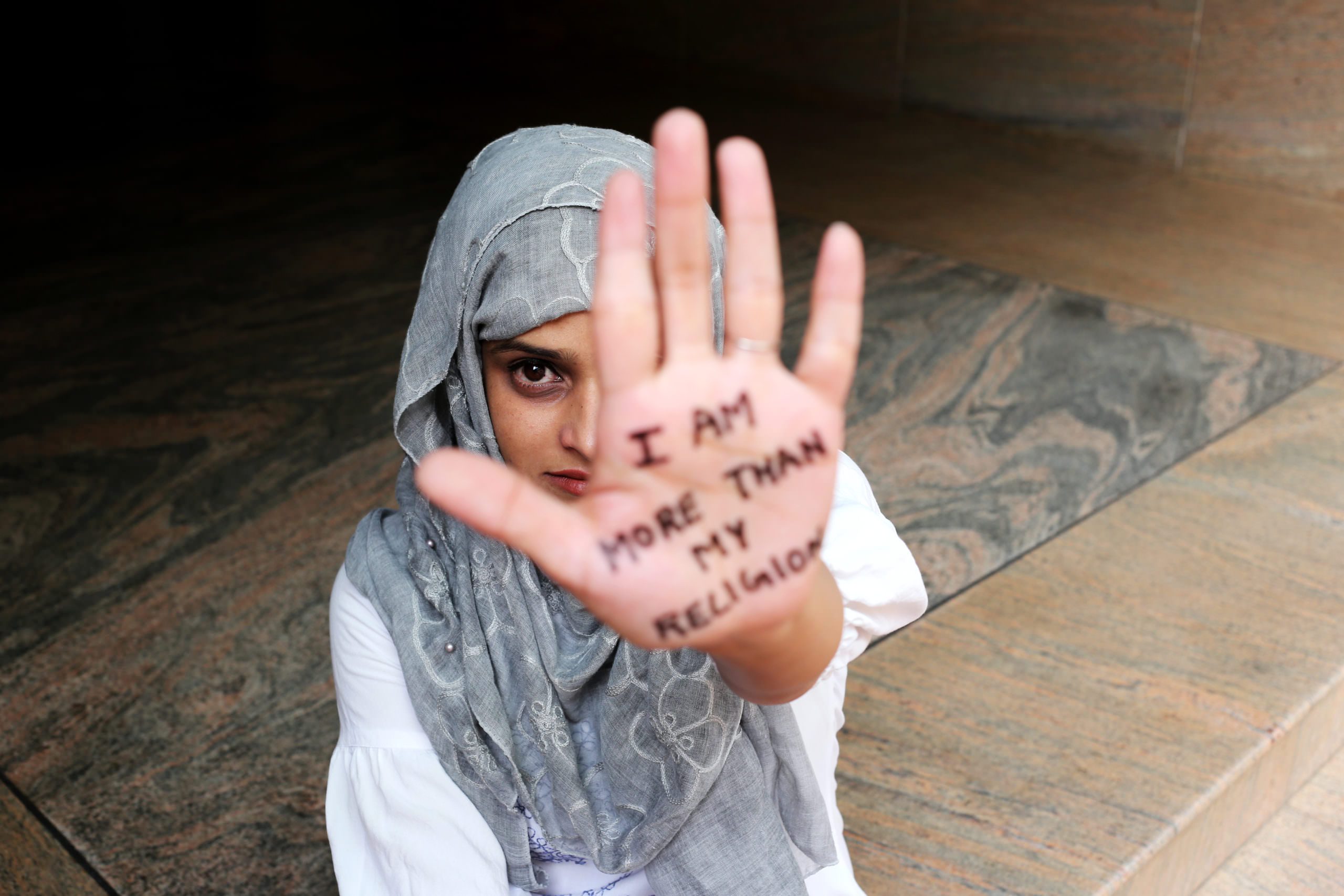

Safdiya

From the series “I am more than a reflection of my mother”

“Safdiya has been living in Bangalore with her friends after the death of both her parents in 2011. She was brought up in liberal environment where her father encouraged her to be self-sufficient and courageous. It’s her father’s ideology that a girl has the right to freedom to express, and his faith in her that has always kept Safdiya afloat in this city of madness.”

S U N A N D A K H A J U R I A

INDIA, PAINTING

Sunanda Khajuria

Sunanda Khajuria is a visual artist who is deeply inspired by Chinese traditional painting techniques and draws her imagery from both the terrain of ethereal memory as well as from actual, physical landscapes she has visited. Khajuria is represented by Art Heritage, New Delhi, India.

After my formal academic study of art, I participated in an Advanced Research Program at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, China, where I studied Chinese traditional painting and calligraphy. Many of my works are deeply connected to nature and its mysterious secrets, where nature is regarded as an avenue to knowledge and a repository of wisdom and holds a great deal of mental and spiritual power. In many of my works, the central figure is a female who finds herself amid nature, shifting landscapes, and a multitude of symbols and objects.

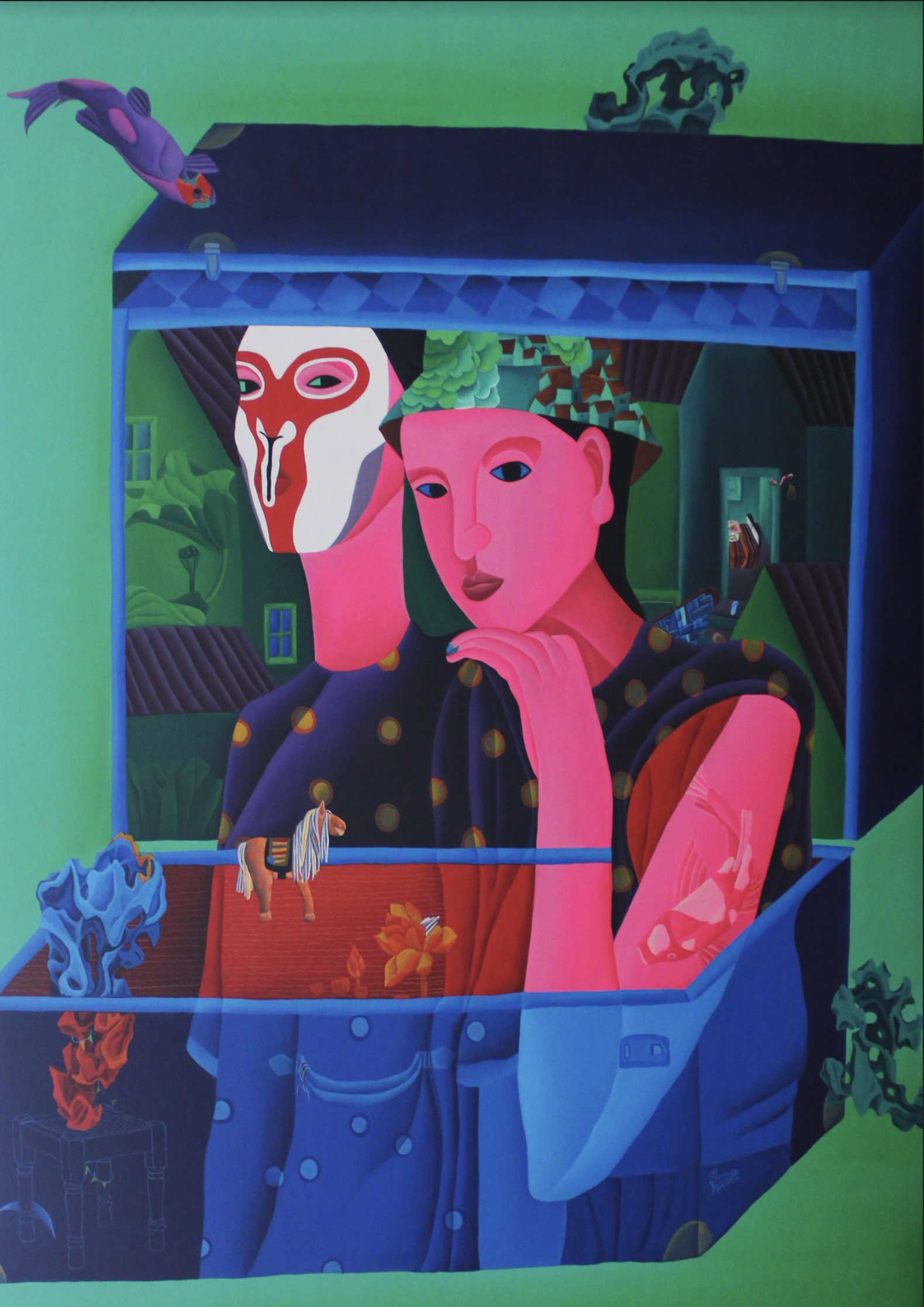

Blue Box

“In this autobiographical painting, I tried to capture my thoughts and early memories through a visual narrative. Each part of this painting reflects a segment of my childhood memories.”

The Cold Mountain

“This painting is inspired by ‘Han Shan’ which means ‘Cold Mountain,’ from Tang Dynasty Poetry. The poems tell the story of the simplicity of life, Taoism, and Zen enlightenment in nature.”

I N S H A M A N Z O O R

INDIA, INSTALLATION

Through performance, video, painting, and textiles, Insha Manzoor informs self-identification as a collective memory and resistance in a country experiencing gender discrimination, strife, and conflict. Manzoor is interested in researching creativity and exploring how artistic and cultural traditions can be crafted to bridge differences, mediate conflicts, contribute to peace.

I was born in 1991, when armed conflict in Kashmir was at its peak. I spent my childhood embracing the snow-white lambs and playing with pebbles on the riversides — experiences that gave birth to the art of questioning the existence of self and its purpose, while searching for love for oneself and a way of life without conflicts.

Insha Manzoor

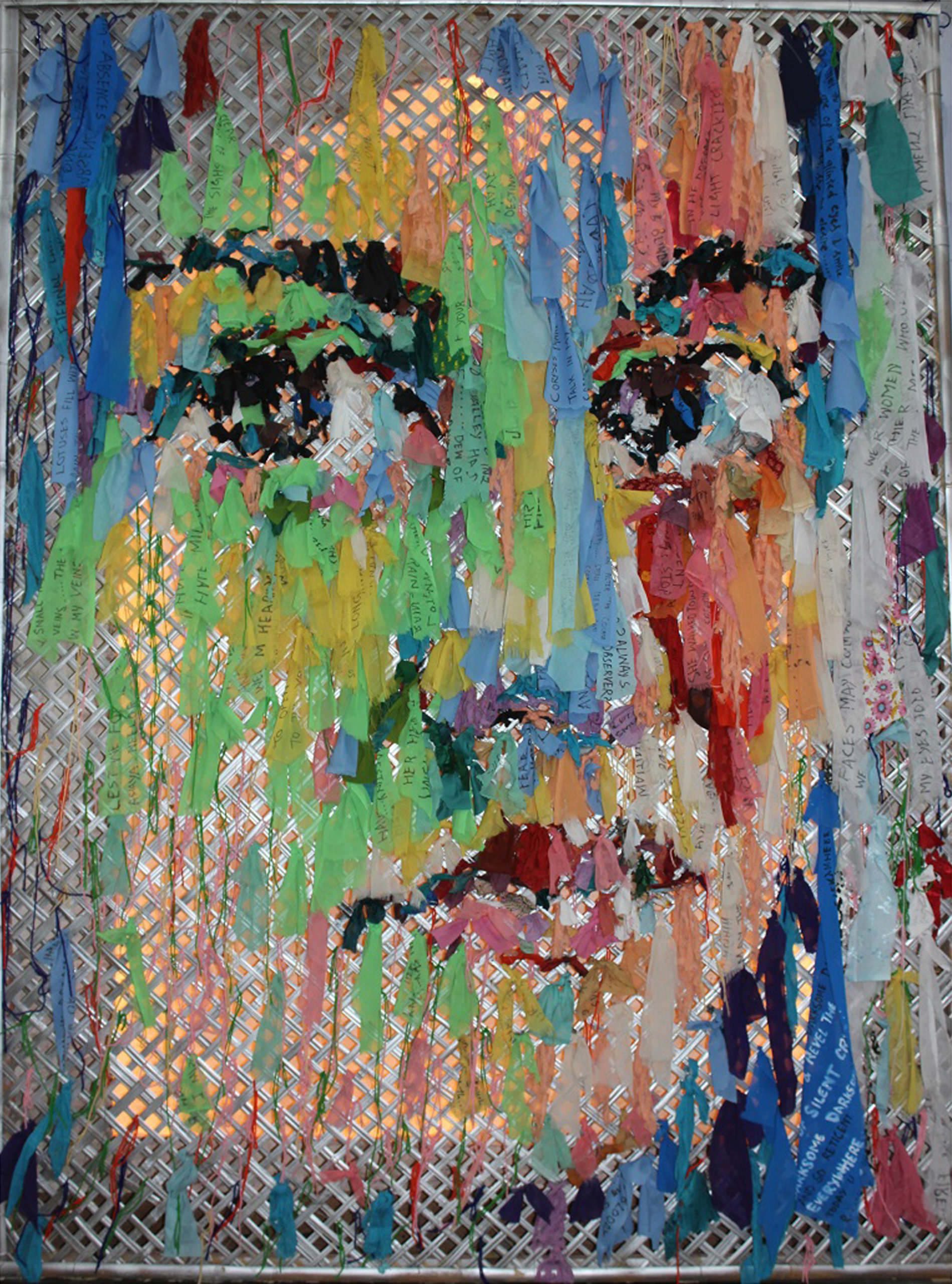

Hidden Connections-II

“A self-portrait carrying the voice of women and bearing text of the undocumented, unaddressed victim who screams, suffers, and longs for justice.”

Connections 04

“This Pheran, the traditional garment of the women of Kashmir, refers to the ritual of knotting cloths and threads, which is sacred when one has a wish and is a ritual of my native land. The work is the voice of the women whose screams are still wandering from hearts to mystic mountains of the valley.”

N A J M U N N A H A R K E Y A

BANGLADESH, INSTALLATION & MIXED MEDIA

Najmun Nahar Keya

Najmun Nahar Keya, a multidisciplinary artist, bases her work on the entire incidence of her past memories, with her present feelings within this current society. Keya is also interested in the dichotomy of human behavior and culture and historical phases to create new conceptions.

My works are a reflection of my life’s experiences, the past and present, combined with my imagination and memories. In my earlier works, I tried to blend in my personal emotions with the socio-political events that surround me, portrayed through symbols and motifs in my self–portraits. My current project is an evolution from my past works, where my memories are compared to my existing circumstances.

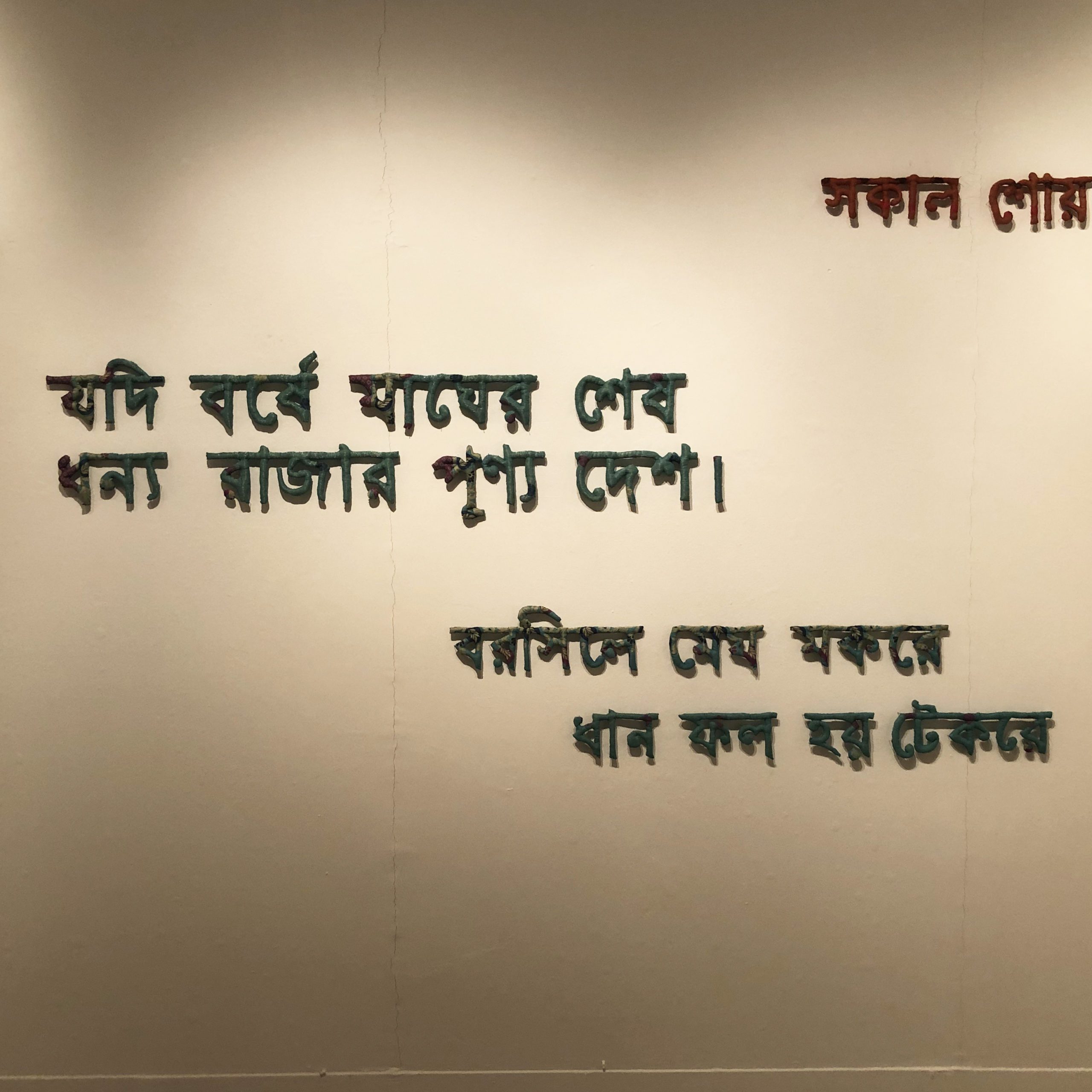

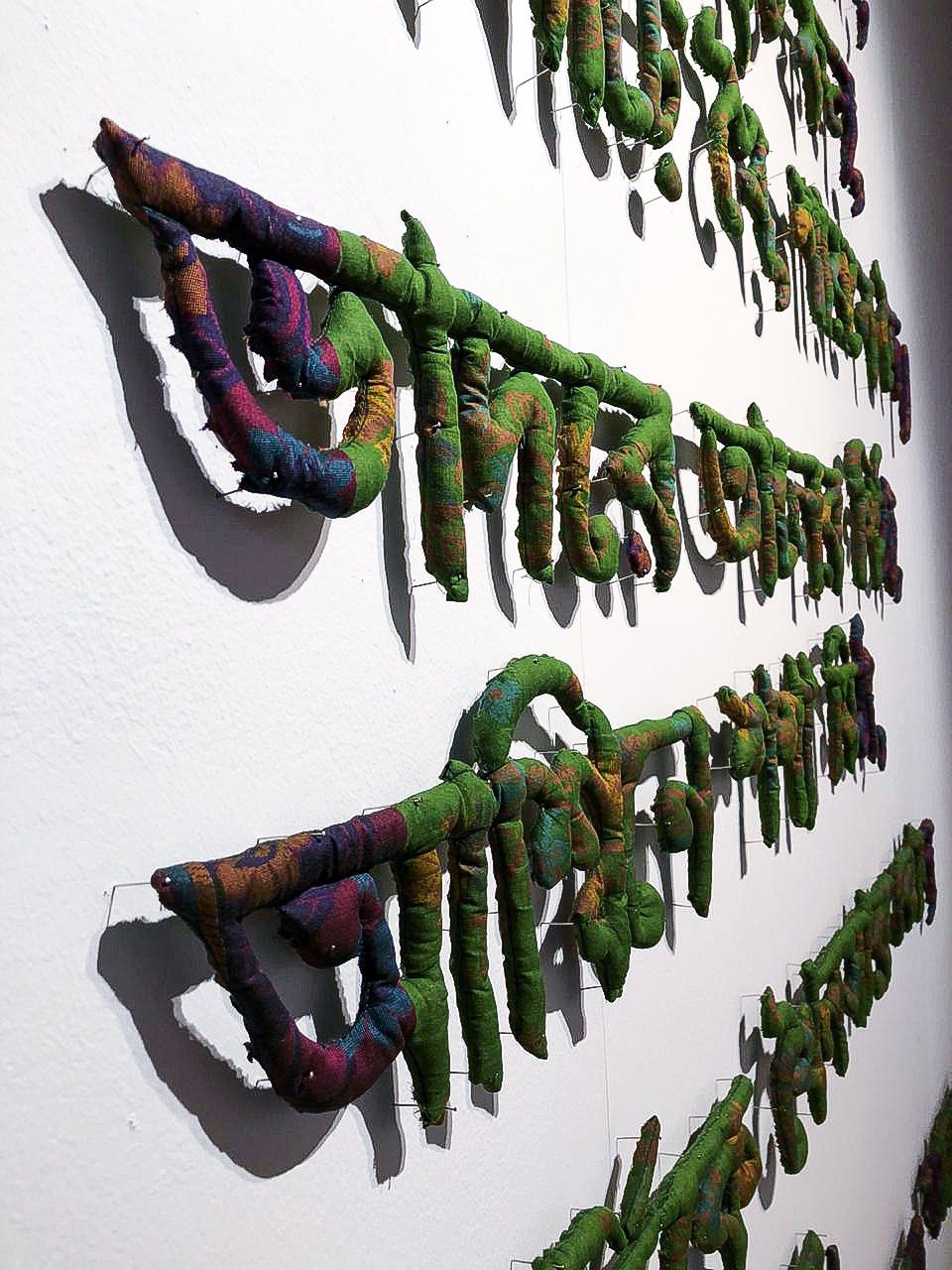

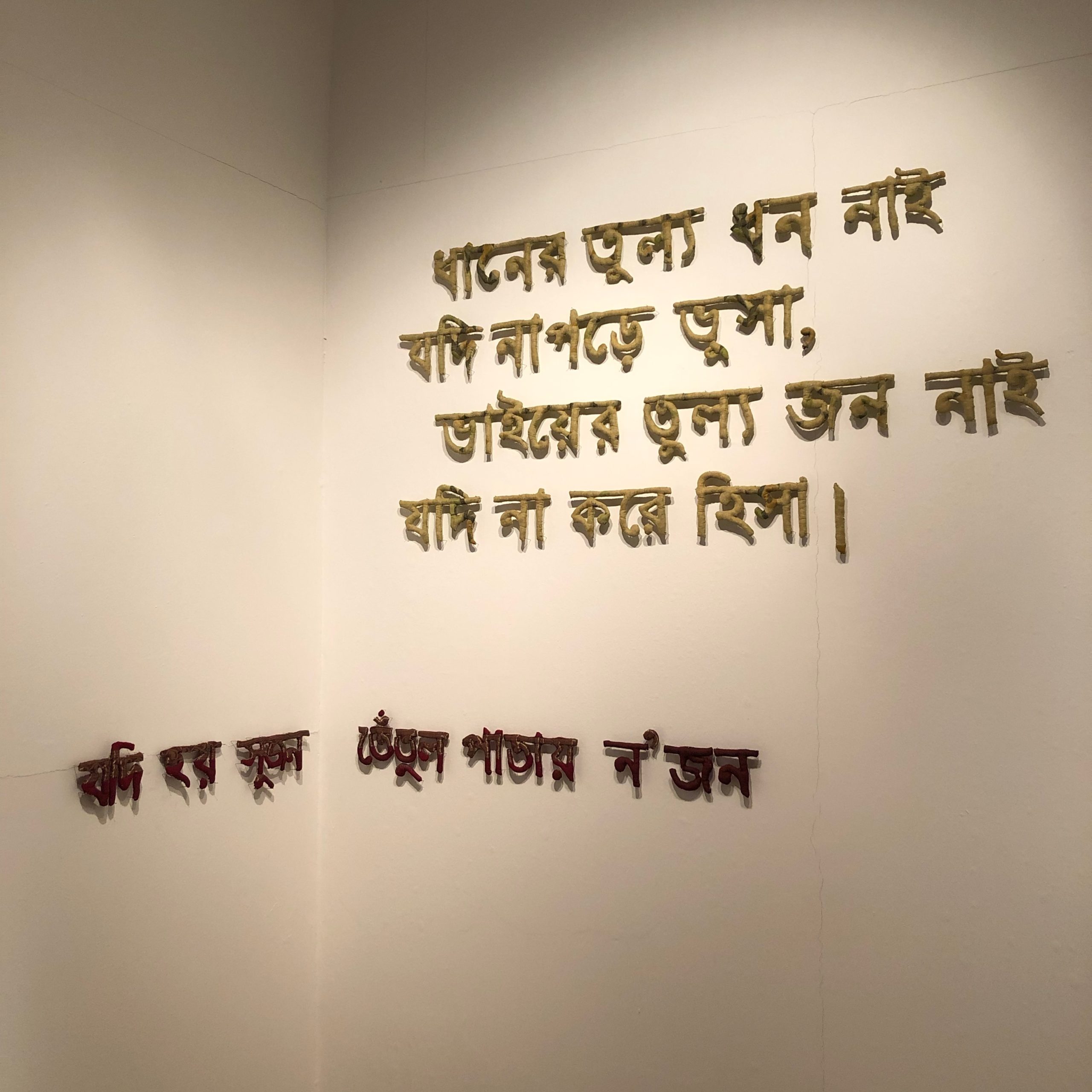

The Spell Song

“Bangla, my national language, has a glorious history and is rich in literature and historical depth. My artwork is composed of texts from Bengali proverbs, which are an integral part of the rich history of the Bengali language and have been passed down for generations in Bengali folklore.”

The Spell Song

“This project shows the rhetorical words of wisdom from Bengali proverbs. I have chosen some very common and popular sayings in Bangla, and created the text using Sari, cotton, and threads, enlisting the help of my sisters and women from my hometown.”

M A H E E N N I A Z I

PAKISTAN, SCULPTURE & PAINTING

Maheen Niazi’s work revolves around the blurred boundaries between religion and culture, where there are no strict demarcations. This corpus of work primarily explores the intersections of religion and culture, and highlights the points of fusion where they merge.

I have chosen a masculine object — which, in a way, is not directly linked to me as a female — because I am trying to comment on the authoritative party of the religion. Using the caps and prayer mat as symbols in my work is rooted in the idea that both items are manmade and complexly woven by people, just as they have made our lives complex with their representation of Islam. Through different perspectives in my work, it shows that with just one object, and no matter how hard we try to see our surroundings differently, these surroundings are very much controlled by men.

Maheen Niazi

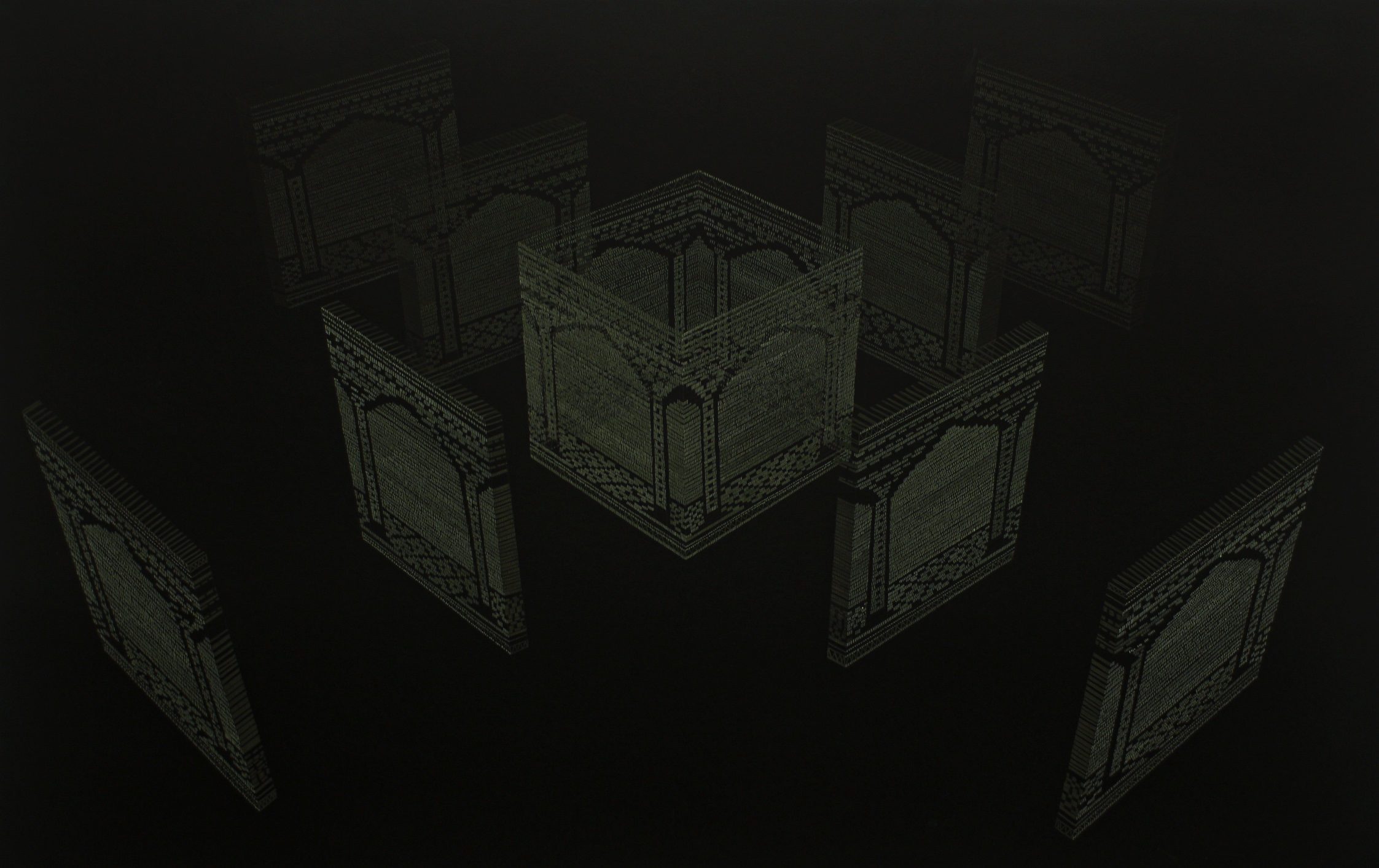

Unboxing

“Multiple transparent layers indicate the continuity of set patterns and void structure in our society. The layers around the cube investigate the multiple man-made perceptions of religion, communicating the concept of walls around us.”

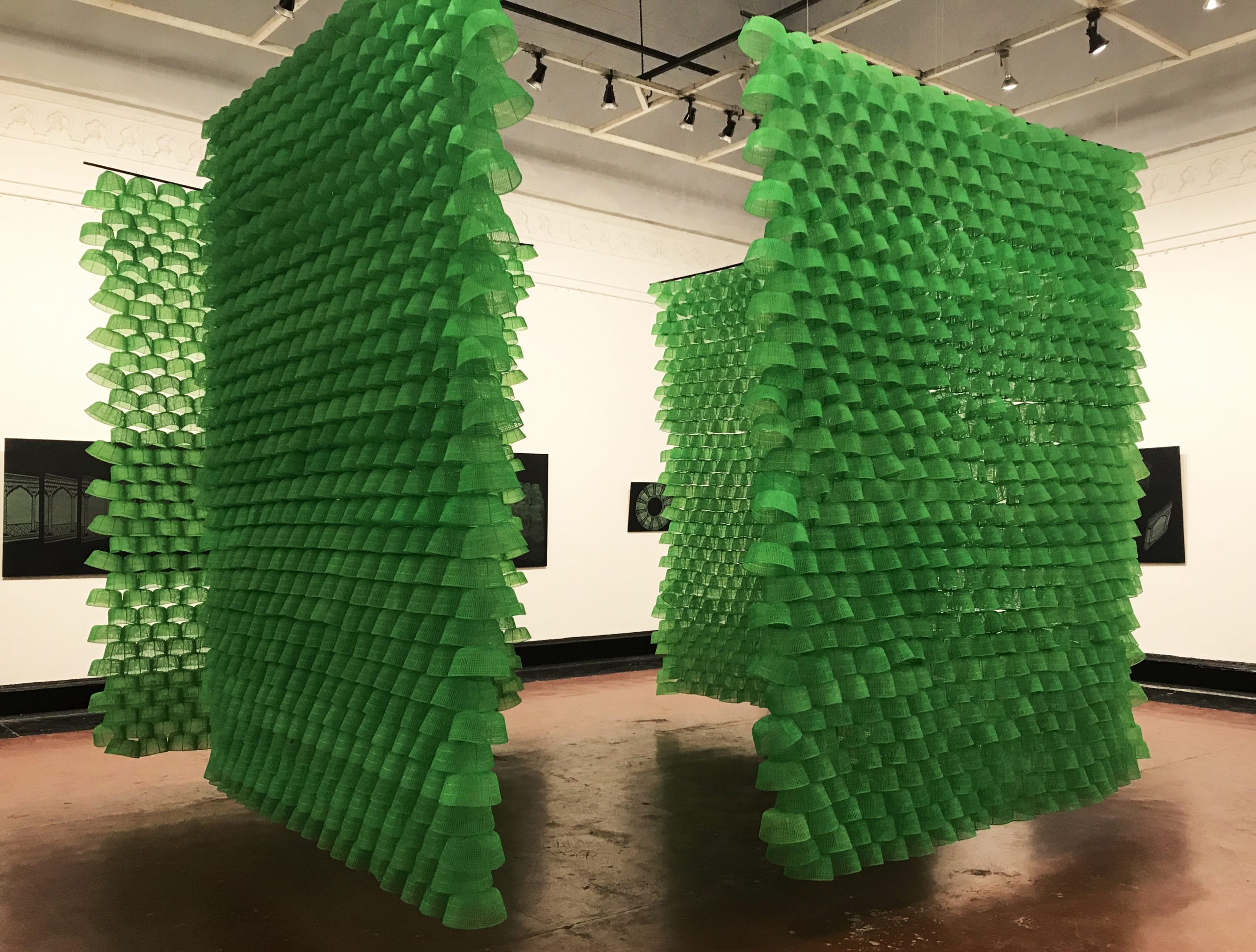

The Hollow Levitation

“This life-sized installation is an assemblage of mass-produced plastic prayer caps commonly found in mosques. It represents an unsealed cube, which acts as a metaphor to symbolize Kaaba (a holy place for Muslims).”

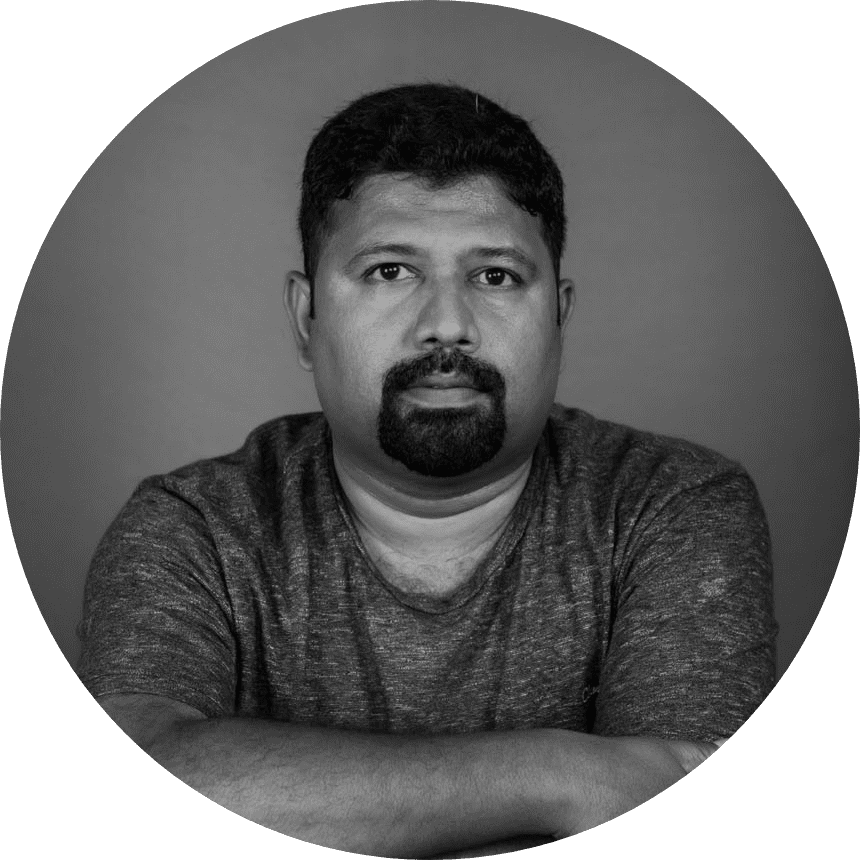

P A T T A B I R A M A N

INDIA, PHOTOGRAPHY

Pattabi Raman

Pattabi Raman is a photojournalist and documentary photographer who specializes in socio-economic and cultural issues. His long-term projects include the post-war lives of Sri Lankan Tamils, gender identity in Tamil folklore, and the aesthetics of a changing urban India.

In contemporary world photography, I keep observing the terms of fragility, agility, perception, resistance, and boundaries — each of which are being visually narrated through multiple experiments. Artists convey their strong feeling about the anti-government stance, their feminist perspective, social isolation, sexual exploitation, and more, in a subtle way.

Transgender Brides

“My series, ‘Transgender Brides,’ presents snippets from the annual Koovagam festival, home to probably the most important and sacred rite of passage for all transgender individuals residing in India. These images shed light on an age-old custom of self-expression, gender empowerment, and identity politics.”

Tamils in Post War Sri Lanka 1

“A woman walks past the ruins of her home in July 2012 on the day she was allowed back to Pudukudirrupu, one of the worst affected areas in northern Sri Lanka. The house was bombed during the war and was further swindled in the name of de-mining.”