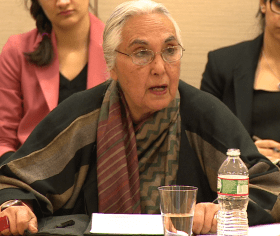

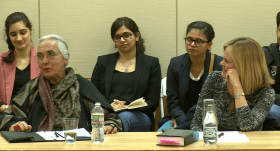

On Monday, May 5, SAI hosted a book talk with prominent Indian historian Romila Thapar about Thapar’s most recent book, The Past Before Us: Historical Traditions of Early North India, which is a panoramic survey of the historical traditions of North India. In the book, Thapar reveals a deep and sophisticated consciousness of history embedded in the diverse body of classical Indian literature.

After summarizing the main arguments of her book, Thapar engaged with the audience in a Q&A session.

Below is a sample of questions asked by the audience:

Audience member: I’m struck by how pivotal kingship seems to be to so many of these different kinds of engagements with the past, whether it’s refracted through monastic traditions or dealing with dynastic issues and biographies. I wondered how far you see kingship as such? Or is that a misunderstanding that kingship is very pivotal to many of these traditions? And does kingship matter?

Romila Thapar: What I was trying to emphasize, actually, certainly was that kingship was very pivotal and has a bearing on politics and governance and so forth, and is therefore important to record. But I was also trying to suggest that there is a transition from earlier forms of kingship that I have called ‘clan-based’ society, but they’re not kingships as such. What interested me very much in looking at the text is that one can see a kind of evolution from a pre-kingship form to a kingship form. And what interests me also is that the change doesn’t necessarily bring about the three independent genres I was talking about.

It’s when kingship develops in a very major way, and, as it were, replicates and moves into areas that are pre-kingship and replicates that process. In that kind of system, I think there is a kind of replication of earlier transitions to kingship, seen much more clearly now because the society has experienced it once before. Therefore, it takes on the character of an independent, external, historical form. There aren’t the same hesitations as there were earlier in the epic tradition. But, yes, kingship is certainly very pivotal. And kingship in the sense of political authority. It’s possible that when we change our definition of history and move away from political authority being important, we will start looking at other things as well. But at the moment, it’s the way it is.

Audience member: Thank you very much for that talk. I am a big fan of your Early India, and I assigned that book to my undergraduates. If you were to write this book again, is there any sort of new framing? Can you share with us, that if you wrote this again, what would it actually look like?

Romila Thapar: I think that the major difference would be that I would probably add on a little more of what people were saying at that time, just in order to draw the contrast between what was said now and what was said then. For example, for the study of the Mauryan period, all of have drawn heavily on his sources, and the Sri Lankan chronicles, and so on.

So there would not be very much more to add. But the orientation would change. We have been drawing on these sources to answer the question of, do we take them seriously or not? Whereas, now, one would say, why are they projecting him in that way? What were they trying to convey to their audience? That would be the slightly different way that I would project it.

Audience member: From our vantage point today, it is very natural for us to make a distinction between written history and mythological history. You presented historical writing itself over a long period of time. Is there any sense that this distinction is being made?

Romila Thapar: I think that the distinction was made, but it wasn’t actually stated as a distinction. I think the distinction was made in small things, like for example in the Sri Lankan chronicles, you have reference to the Buddha flying to Sri Lanka, to choose the location for where the major monasteries would be located. Now, I’m pretty sure, that most people realized it was symbolic reference, that these places weren’t arbitrarily chosen.

Where I think that the distinction is made is in this tripartite section that I was talking about. I am personally very impressed by the basic argument. The first section was quite overtly mythological. I think the fact that they leave out any type of attempt to be historical in this section is an indication of it being mythological. You have to begin somewhere, so you begin in this great golden age where nobody knows what happened. And then comes the flood, which wipes out this age. And when the waters recede, history begins. So I think that kind of distinction is being made between myth and history.

Audience member: I was wondering whether your interpretation of what you call ‘time-marking,’ for example a shift from clan-society to kingship, as represented in this text, got me thinking about whether writing history today as well as in the past has always ultimately been about establishing narratives of legitimacy, hierarchy, and in some ways, asserting ideas about power, even forms of colonial power. Is your work intended to say that history is to be seen with a certain amount of concern, because it can’t every separate itself from the effort to legitimate (power, the present over the past)? Is it a cautionary tale?

Romila Thapar: Yes, I suppose up to a point, it is. What I’m trying to suggest is that, to put it crudely, one must be suspicious of all sources, and try and understand what it is they are intending to say, which we don’t always do. Very often, we take things at face-value. I think we have to go a little deeper into this and find out why they’re saying it that way, what they’re trying to say, and who they are addressing. In other words, be much more analytical about these questions relating to history that we have seen so far. That is certainly essential.

Romila Thapar: Yes, I suppose up to a point, it is. What I’m trying to suggest is that, to put it crudely, one must be suspicious of all sources, and try and understand what it is they are intending to say, which we don’t always do. Very often, we take things at face-value. I think we have to go a little deeper into this and find out why they’re saying it that way, what they’re trying to say, and who they are addressing. In other words, be much more analytical about these questions relating to history that we have seen so far. That is certainly essential.

Whether history will continue to be history of those in power – it obviously will change, because the people who are using history for legitimation, it will gradually widen out, as is happening today in India, where you’ve got caste groups coming in. So it’s not just those in political power legitimizing themselves, but it’s also those aspiring to be somewhat different and in a superior status to where they are in the moment, who then resort to rewriting the history. That brings in a different kind of history. Now you’re into social and economic history. The context then becomes much more important.

SAI talked to audience members to get their impressions of the talk:

“Roman historians like myself have been increasingly committed to exploration beyond the Mediterranean, and early India is particularly interesting to us both because of contacts between Rome and India and in terms of comparative study of premodern regimes. Romila Thapar is the foremost authority on early India, and has done so much to make early Indian history accessible to a broader scholarly audience, so the chance to meet her and engage closely with the ideas of her latest book on historiography was exciting and important to me. Romila Thapar’s approach to questions about the variety of engagements with the past in early North India, the subject of her most recent book and of her talk, resonates deeply with me, since I am particularly interested in the variety of ways of approaching and systematizing time and the past in societies of the Roman world.”

-Emma Dench, Professor of the Classics and of History, Harvard College Professor, Director of Graduate Studies, Department of the Classics, Harvard University; Chair of the event

“It was an honor to hear Romila come speak to us. I remember as a schoolboy, having to read her book, although I can’t say I read it with great enthusiasm given the length… but I’m glad I did and it was a pleasure to be reminded of such great scholarship [at the book talk].”

–Tarun Khanna, Director of the South Asia Institute, Jorge Paulo Lemann Professor, Harvard Business School

“Professor Thapar’s talk was very illuminating on the multiple textual traditions in early India of perceiving and representing the past. She spoke eloquently on understandings of time, for example, in the theory of the yugas (epochs), in which human societies are seen to be continually transforming within a vast cosmological cycle of time. One hopes to read more in her book about how these texts and traditions might also have imagined the future of humanity and the earth.”

–Shankar Ramaswami, SAI South Asian Studies Postdoctoral Fellow

“It was an impressive and thoughtful presentation, putting the Indian history straight. Thapar is a known historian and here she very excellently explained emerging and alternative historical tradition of India. Her work will definitely help all those interested in early Indian history.”

–Mumtaz Anwar, SAI Research Affiliate