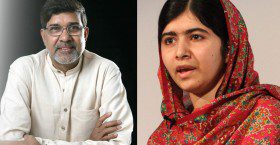

The Harvard South Asia Institute is thrilled to hear the news that Kailash Satyarthi of India and Malala Yousafzai of Pakistan have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for 2014 for their incredible efforts in improving the lives of children worldwide.

Kailash Satyarthi has followed in Gandhi’s footsteps in promoting peaceful and nonviolent means to ending the grave exploitation of children and promoting children’s rights. Malala Yousafzai became an international spokesperson for the right of girls to education after being shot by the Taliban.

“We should, in our own small way as the South Asia Institute, capitalize on the attention towards these important social issues that these Peace Prize awards will generate,” said Tarun Khanna, Director of SAI and Jorge Paulo Lemann Professor, Harvard Business School. “SAI does a lot of work on gender-related issues, and increasingly on education of children, and it behooves us to redouble those efforts.”

SAI spoke with Jacqueline Bhabha, FXB Director of Research, Professor of the Practice of Health and Human Rights at the Harvard School of Public Health, the Jeremiah Smith Jr. Lecturer in Law at Harvard Law School, and an Adjunct Lecturer in Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, whose own research focuses on human rights, trafficking, and gender in South Asia, on the significance of the awards.

SAI: What do you think stands out about the work that these two figures have done, that got the attention of the Nobel Peace Prize committee?

Jacqueline Bhabha: I think what’s really interesting is that on the one hand you have somebody [Satyarthi] who is a mature, seasoned human rights activist, who is well known to people working on child labor, and child exploitation for decades, and has really been in the trenches and has taken enormous personal risk and sacrifices to carry on the work he has done with a range of different strategies: working with trade unions, mentoring children, and using the courts. He has been a tremendously creative and inventive human rights advocate.

And on the other hand you have this young teenager [Yousafzai] who shows incredible personal courage in one extraordinary incident, and has built on that to make quite a focused campaign on gender and education. So there is an interesting contrast in strategy, skill sets, and experience. But in both cases, clearly, what the Nobel committee was struck by was the vision and courage of two very different individuals.

SAI: What do you see as the significance of giving the award to both an Indian and a Pakistani at the same time?

JB: It’s interesting, in that it draws attention to South Asia, which is a critical hotspot for children’s rights, which is important, even though issues of infant mortality and morbidity are very much widely spread – plus, incidents of child rights abuses happen everywhere, South Asia is a particularly dark spot when we look at child labor, child marriage, and sexual slavery. So I think drawing attention to the continent rather than one country is interesting.

However, there is nothing quintessential about South Asia which says this region has to be mired in child rights abuses. Bangladesh has made enormous progress as a poorer country with very complicated political history and lots of natural disasters, yet has made progress on both child labor and girl’s education, and has made dramatic strives compared to India and Pakistan. So I think that’s a point worth making, that even though South Asia is a very dark spot globally, there are little tiny pockets within South Asia of very good practices.

SAI: Will this award help in bringing attention to these issues in South Asia, and worldwide?

JB: Absolutely. I do think it will do that for both the Indian and Pakistani government, but more generally, it will really draw attention to the pervasive reality of crimes against children.

I think one other point that’s worth making is that in a way, Kailesh and Malala represent two points of extreme on the spectrum. One of them draws attention to one of the worst abuses, and a lot of [Kailash’s work] in rescuing children from slavery really brought attention to the endemic nature of these kinds of violations. On the other hand, Malala represents the critical preventative strategy for trafficking, which is education – the best way of addressing the poverty, destitution and entrapment of children – through enhancing their education to help them escape from illiteracy and exploitation. So the two different awards really cover the spectrum.

SAI: How do you see the work that they are doing possibly translated outside of South Asia, to other countries?

JB: I think these examples are much broader than their relevant countries. Both these people have a global significance, and I think the strategies in countering child labor, for example, thinking about rescuing, thinking about organizing, thinking about globalization of workers, are strategies that have been adopted by countries in Latin America. I think the whole connection between gender and education is something that also is worth thinking about much more broadly.

I think this [award] is something that advocates can use and I think that politicians will have to pay attention to.

SAI: Malala was already such an international figure in the media, but Kailash wasn’t as widely known. Do you think this award the potential to catapult his platform to the forefront?

JB: Of course. It happened with Shirin Ebadi years ago, the Iranian peace laureate, when no one outside of Iran had really heard of her work. Then, it became a flashpoint of people talking about human right violations in Iran, and persecution in Iran. Although some of us have followed Kailash’s work for decades, he wasn’t as much of a household name as Malala. This will certainly be something that will raise his profile and the many different strategies he has used to address child labor.

This interview has been edited lightly for clarity and length.