By Ghazal Gulati and Divya Sooryakumar, Ed. M Candidates, International Education Policy, Harvard Graduate School of Education

“We have a moral imperative to end open defecation and a duty to ensure women and girls are not at risk of assault and rape simply because they lack a sanitation facility.”

-UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, Message for World Toilet Day, Nov. 19, 2014

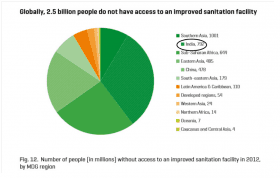

Worldwide, 2.5 billion people do not have access to proper sanitation. Of the 1 billion of people in the world who defecate in the open, half of those reside in India. The country faces a challenge in meeting the 2015 UN Millennium Development Goal, which aims to “halve, by 2015, the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation.”

The theme of this year’s World Toilet Day, which took place on Nov. 19, 2014, is “Equality, Dignity and the Link Between Gender-Based Violence and Sanitation.” The campaign seeks to put a spotlight on the threat of sexual violence that women and girls face in developing nations, due to the loss of privacy as well as the inequalities in access to safe sanitation.

On Monday, November 17th, SAI hosted a Gender and Urbanization seminar on the topic with Sharmila Murthy, Assistant Professor of Law, Suffolk University; Visiting Scholar, Sustainability Science Program, Harvard Kennedy School, Ramnath Subbaraman, Associate Physician, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; Research Advisor, Partners for Urban Knowledge, Action, and Research (PUKAR), Mumbai, India, and Subhadra Banda, Research Associate, Centre for Policy Research; MPP Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School, titled ‘Access to Toilets and Women’s Rights.

By approaching the issue of access to toilets from multiple perspectives of public health, law, and civil society, the three panelists dove deep into the intricacies of the issue, and into the connection between sanitation, toilets, and gender violence, often a taboo topic in India.

Setting the context, Murthy explained that only recently has access to sanitation also become closely tied to women’s rights due to the tragic events this summer in Uttar Pradesh, where two young girls were brutally raped and murdered when they went to defecate openly in the night.

“Waiting until nighttime to urinate or defecate is not only dehumanizing, it makes women vulnerable to sexual assault, as vividly illustrated by the appalling events in India,” Murthy wrote in an article about access to toilets in India.

To understand the dynamics between gender and sanitation, the panelists first unpacked the complexities of the public provision of sanitation in India.

Dr. Subbaraman dove into his research on the interplay of water scarcity and sanitation. “Death and malnutrition are inescapable in India,” he pointed out, referring to his research in the slums of Mumbai. He argued that often the issue of water, specifically access to safe drinking water, is a prime focus, while sanitation is put on the backburner.

However, Dr. Subbaraman’s research showed that there is an undeniably strong association between open defecation and child stunting in India. Unfortunately, evidence from two control trials in Odisha and Madhya Pradesh shows that building sanitation facilities does not increase the usage of cleaner facilities, as a majority of the participants continued to engage in open defecation.

“The evidence from India suggests that simply building toilets is not enough — there also needs to be demand,” writes Murthy. “Open defecation is a traditional practice in rural India, and cultural biases can impede actual toilet usage. Even after a toilet is constructed, a family may use it for storing, bathing and washing purposes, but not for defecation.”

During the seminar, Subhadra Banda presented her work with the Centre for Policy Research in Delhi, where she spent time researching slums in Delhi. She explained that access to sanitation varies greatly from rural to urban areas, with greater demand for toilets in urban areas.

Yet, because of the labyrinth of public agencies, demand has outpaced supply. Banda described the plight of a woman in Delhi who, despite repeated attempts, was unable to trace who was responsible for the maintenance of the public toilets in her community. Being a lawyer by profession, Banda also highlighted how legal precedents cemented inequalities by placing more value on the comforts of “urban elite” over the basic sanitation rights of the urban poor.

After uncovering the intricacies of sanitation access the panelists then discussed the role of gender in this complex issue. They shared evidence that points to the disproportionate burden that women bear when access to sanitation and water is limited, for example, the burden of physically collecting water to bearing the acute tension of a potential water shortage.

Murthy then discussed the recent policy initiatives and the emerging role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in improving access to toilets in India. Seminar attendees also commented on the pervasiveness of the issue across other countries in South Asia, specifically in Bangladesh and Nepal.

“Improving access to sanitation requires change across several scales of power. India needs to tap into its long-tradition of women’s self-help groups to promote critical peer-to-peer education, highlighting toilets as an issue not only of public health, but as one of safety and dignity,” writes Murthy. “Finally, technical solutions to the sanitation problem must never reinforce old caste-based and gender-based hierarchies.”

The seminar left attendees with an understanding of the long road ahead in ensuring access to the basic human right of sanitation, especially for women.

In India, Dying To Go: Why Access To Toilets Is A Women’s Rights Issue by Sharmila Murthy