This is the first in a series of profiles of Harvard alumni who are young entrepreneurs in South Asia.

By Soujanya Ganig, Ed. M Candidate, Harvard Graduate School of Education; SAI Student Coordinator

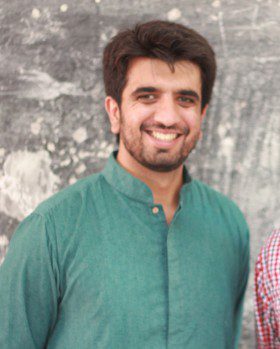

Imran Sarwar is the Co-Founder & Managing Director of Rabtt, an organization based in Pakistan that aims to change the education landscape by connecting with students at a personal level, and catering to their individual talents through intensive summer programs and year-round workshops. The organization has already impacted 1600 school students and 350 university students. He founded Rabtt after graduating from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government with a masters degree in Public Policy.

Imran Sarwar is the Co-Founder & Managing Director of Rabtt, an organization based in Pakistan that aims to change the education landscape by connecting with students at a personal level, and catering to their individual talents through intensive summer programs and year-round workshops. The organization has already impacted 1600 school students and 350 university students. He founded Rabtt after graduating from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government with a masters degree in Public Policy.

SAI recently spike with Sarwar about his organization, and what it is like to be an entrepreneur in South Asia.

SAI: You’ve said that Rabtt has taught you the value of experimenting and taking first steps. How easy is it to take those first steps in Pakistan? Is there an entrepreneurship- friendly environment?

Imran Sarwar: It’s not easy to take those first steps. It is not easy anywhere in the world, and it is especially hard in South Asia. And even when we have taken those first steps, it takes so much convincing and explaining. This is because there is a culture around failure and there is no value in experimentation. It is different; in the United States failure is respected.

However, it is amazing how things start working out once you take the first step. People are willing to support you and there are role models who have done similar things before you that you can learn so much from.

SAI: What experiences at Harvard spurred you to go back to Pakistan and start Rabtt?

SAI: What experiences at Harvard spurred you to go back to Pakistan and start Rabtt?

IS: I am a Fulbright scholar, so I had to come back to Pakistan for at least two years after graduation. After coming back from Harvard there are certain expectations that you would work at the World Bank or the United Nations. But I felt that if I went to Harvard and still didn’t pursue what I wanted, then there was no point getting that education. The whole point of education is liberation and freedom to pursue whatever you want.

Harvard also helped me develop a sense of audacity to follow what I wanted to do. There was a very receptive environment here and the wide spectrum of courses allowed me to keep experimenting. I was well supported by Tarun Khanna [Director of the South Asia Institute] and my classmates.

SAI: Can you shed some light on the entrepreneurship space in Pakistan? Is there a vibrant atmosphere for start-ups?

IS: In Pakistan, I am surrounded by people starting wonderful enterprises. Therefore, for me, it is a flourishing space. I am currently working on staring a co-working space to get entrepreneurs together. There are also a lot of technology start-ups in Karachi, Islamabad, Lahore, and Peshawar.

SAI: What were some of the biggest challenges you faced while starting Rabtt?

IS: There were mainly three sorts of challenges:

One, logistical- We started working with public schools in the beginning. Public schools, as opposed to private schools, are a whole different ball game. We had to navigate through bureaucracy and red tape. And at the school level, the headmasters were wary of us and would not let us operate unless we had the prerequisite permissions. We used our connections to smoothen the process.

Two, general reception to the idea- We are not entering schools with the intention of teaching science and math. We had to create demand for modules that are not normally covered in schools. We work towards improving core competencies of critical thinking, tolerance, and creativity. The fact that people are now paying for it (Rabtt charges one segment and provides it free of cost to the other segment) is a market validation of our work.

Two, general reception to the idea- We are not entering schools with the intention of teaching science and math. We had to create demand for modules that are not normally covered in schools. We work towards improving core competencies of critical thinking, tolerance, and creativity. The fact that people are now paying for it (Rabtt charges one segment and provides it free of cost to the other segment) is a market validation of our work.

Three, finances- Right now, we have funds only for the next month and half. We have come to accept that finances will always be a problem and that we will be dealing with on a constant basis. Over time, I’ve realized that things work out. If you are in it for the long run and work hard for it, the world will make it happen for you.

SAI: Rabtt is now 5 years old. What do you hope you could have done differently in the initial years of starting the organization?

IS: There have been a lot of learning points and instances where we have faltered and we have learned from them. For example, in the beginning, we tried selling our workshops for five times the fee we are charging right now. Another example is our young professionals program. I spent 2-3 months actively supporting this project, and as a result the other operations suffered. We eventually had to put it on the backburner.

But I don’t think I would have done anything differently. I have also been very lucky to have a great team. We have 5 people who work full time and 50 fellows. We hope to scale to 90 fellows next year.

SAI: How important is entrepreneurship for young people in developing countries or in economies where jobs are hard to find?

IS: Entrepreneurship has been very beneficial to me personally. It gives a depth of purpose, makes you take risks, strengthens decision making power, makes you take on real life challenges and gives you a broad skill set. I have traveled all across the city to look for an office space and set it up; I work with students, mentors (college graduates), parents of students in public schools and low-income private schools, high net worth individuals; I work with the financial team to forecast the growth of the organization and I am also marketing the work of Rabtt all the time. Entrepreneurship lets you get your hands dirty in the real world.

SAI: As an organization in the social space, would you say it is a challenge for interventions like yours to bring about a change in Pakistan?

SAI: As an organization in the social space, would you say it is a challenge for interventions like yours to bring about a change in Pakistan?

IS: This depends on a person’s perspective. In the last two and half years I have become an optimistic person. When you’re operating outside the system, people will keep telling you all that is wrong. I don’t mean to romanticize entrepreneurship, but when you take the first step, the landscape changes and you see opportunities instead of challenges.

Rabtt means to connect, and human connections are at the core of all that we do. There is a lot of anecdotal evidence that tells us that there is value in our work. Though I am not sure about a paradigm shift, we have to take the first leap and start pursuing our path.

SAI: What would you like see happening in education in Pakistan in the next five years? What should be prioritized?

IS: There are 25 million kids out of school in Pakistan. There are a lot of government-sponsored enrollment drives, but my hunch is that most of them fail. Kids are not going to school because they are not happy in school, and feel that the education they receive there is of little or no value. Therefore, even the quantity debate is a quality issue. If you provide a meaningful education then there will not be an enrollment issue. And there should be meaningful education which is specific to the environment. For example, there is a school in rural Punjab which teaches basic agriculture studies in primary and secondary education.

Hence, education should be demand-driven and not supply-driven. The metrics of critical thinking, tolerance, creativity, and empathy that we are working on are close to our heart. Education should propel students to think more critically and empathetically.