By Jane Philbrick, with Maria Letizia Garzoli, MDes Critical Conservation Candidates, Harvard Graduate School of Design

By Jane Philbrick, with Maria Letizia Garzoli, MDes Critical Conservation Candidates, Harvard Graduate School of Design

The following essay is based on Philbrick and Garzoli’s experience in the Harvard Graduate School of Design studio ‘Extreme Urbanism III: Planning for Conservation,’ taught by Rahul Mehrotra, which explores interventions at the intersection between critical conservation and urban planning and design for Agra, India, an exemplar of contemporary urban challenges.

A brutally frank, recently published New York Times Op-Ed, “Holding Your Breath in India,” gives the authors of this text pause. How to persist in matters as rarified as Imperial Mughal-era cultural heritage amidst the escalating crisis of India’s toxic urban centers? Now-former Times South East Asia correspondent Gardiner Harris recounts the chilling physical toll exacted on India’s youngest city dwellers, children whose physical capacities are stunted, lungs wasted by polluted air, life expectancies cut by the poisons they live with day after day. Medical facts: a child raised in one of India’s 14 of the world’s 25 most-polluted cities[i] will suffer respiratory impairment; diminished IQ; chronic gastro-intestinal illness from exposed, pestilent street-level gutters conveying human and animal effluence and industrial waste, prevalent open defecation, and bathing in and drinking from the slow coursing sewer drain that the magnificent Yamuna River becomes in the nine non-monsoon months of the year, into which spews raw sewage and waste, measured in terms of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), at a rate escalating from 117 tonnes per day (tpd) in 1980 to 276 tpd in 2005.[ii] Offering anecdotal evidence that underscores how endemic and systemic the crisis has become — the rule, not the exception — Harris reports discovering that the water tanks of his four-year-old Delhi apartment complex had been contaminated by sewage channels illegally dug by the developer. Prising the floor tiles to investigate the source of foul odors emanating from his sink and shower taps, “brown sludge,” he writes, “seemed to be everywhere.”[iii]

The precipitous growth fueling India’s catch-up first-world economy and its ruinous, petrochemical wake obscure an older, much wiser India, urgently needed. Not just by India, but by our “One World,” to reference American composer and philosopher John Cage, whose work was deeply influenced by Indian mysticism and Hinduism. The Yamuna River flows southerly 855 miles (1,376 kilometers) from its point of origin in the Himalayan foothills to join the River Ganges, Hinduism’s most sacred river. The Ganges courses another 900 miles (1,448 km), discharging into the Bay of Bengal to meet the Indian Ocean, bracketed east and west by the Oceans of the North Pacific and the South Atlantic. Northeasterly trade winds fan India’s toxic air across the Arabian Peninsula and northwestern Africa, toward the South, Central, and southern North Americas, and to the south, merging with southeasterly trade winds that sweep south-central Africa towards South America. This one, swirling world of tides and currents demonstrates that the crisis of India’s air and water is not India’s alone. Seeking mitigation and resolution, we discover the sustaining remedies of India’s ancient self. Examining these old wisdoms, expressed in cultural practices traced in artifacts dating more than 500 years old, we retrieve possibilities for a way of being that may sustain us – materially and spiritually – for the next 500 years, and beyond.

Agra’s Mughal Riverfront Gardens: Historical Overview

Agra’s Mughal Riverfront Gardens: Historical Overview

Agra’s Mughal riverfront gardens date from the conquest in 1526 of the Chagatai Turkic prince Babur, descendant of Emperor Timur on his father’s side and the Mongol Emperor Genghis Khan on his mother’s. Detesting the arid landscape of India’s northern plains, and longing for the lush Samarkand gardens (present day Uzbekistan) of his youth, Babur immediately began construction of Ram Bagh (“Garden of Repose,” also known as Bagh-i-Nur Afshann [“Light-Scattering Garden”]) in the lineage of the Ottoman garden with its typology of a walled oasis, nourished by the Uzbek region’s fertile soils and irrigated by canals drawn from the River Zarafshan.[iv]

“Then in that charmless and disorderly Hindustan, plots of garden were laid out with order and symmetry, with suitable borders and parterres in every corner and in every border rose and narcissus in perfect arrangement.”[v]

In so doing, Babur inaugurated a nearly 200-year tradition of Mughal imperial garden construction, which reached its apex with the Taj Mahal, commissioned by Babur’s great-great grandson Emperor Shahjahan in 1632. The reign of Mughal Emperor-Garden-Builders ended with the death of Aurangzeb, Babur’s great-great-great grandson, in 1707. Although the dynasty persisted until 1857, no significant Mughal gardens followed after Aurangzeb.

Transforming the native landscape from arid plain to garden oasis facsimiles of “little Kabul” required aesthetic imagination and technical prowess. Exquisite ecologies of lush vegetation framed by pavilions and pathways engineered to convey cooling waters for irrigation, drink, hygiene, and comfort set the stage for the performance of courtly life, a social theatre of state and cultural practice.

Water

The critical task of irrigating Agra’s Mughal gardens entailed extracting water from the Yamuna River and harvesting rainwater. The Yamuna is fed by two sources: snowmelt from the upstream Himalayas and monsoon rains, which swell and flood the riverbank from July to September, with snowmelt contributing just 5% of the largely monsoon river’s flow.[vi] Reserves stored in underground cisterns, constructed of brick with lime mortar, sustained the gardens during the nine-month-long dry season. Animal-powered water lifting devices such as the Persian Water Wheel (raha), fabricated from wood with ceramic or leather buckets, captured water from depths up to 20 meters. The Persian Wheel is a mechanical system comprising a wheel connected to another toothed wheel, attached below ground level to a vertical shaft, which itself is attached to a horizontal wheel at ground level via a horizontal beam yoked to draft animals, oxen or bullock. The animals circulate a post to activate water lifting, whereby the water is released when the bucket reaches the top and flows into the cistern or along a water channel in the garden pathway-cum-infrastructure aided by gravity. The average capacity of the water wheel system is 10,000 liters per hour from a 9-meter depth, with one pair of bullock.[vii]

Water conveyance above ground was conducted via shallow channels that combined delivery of water for garden irrigation with the pleasing aesthetic of running water glinting sunlight in the daytime and the flickering flame of oil lamps in the evening, animating with mercurial vitality the austere geometries of the Mughal garden pathways and pavilion architecture. Open channels sluiced water through interior chambers, streaming under the bed, for instance, of the future Emperor Akbar, Babur’s grandson, at his Imperial capital Fatehpur Sikri (1571-85), to afford cooling comfort in the high heat.

Water conveyance above ground was conducted via shallow channels that combined delivery of water for garden irrigation with the pleasing aesthetic of running water glinting sunlight in the daytime and the flickering flame of oil lamps in the evening, animating with mercurial vitality the austere geometries of the Mughal garden pathways and pavilion architecture. Open channels sluiced water through interior chambers, streaming under the bed, for instance, of the future Emperor Akbar, Babur’s grandson, at his Imperial capital Fatehpur Sikri (1571-85), to afford cooling comfort in the high heat.

Underground, terra cotta pipes conducted water from river-fed cisterns and traditional rain water-harvesting stepwells (baoli). Above ground, the aesthetic pleasure of flowing water was heightened by the hand-carved scalloping of water chutes (chadhar) that exaggerated turbulence as the water issued from apertures in the high-to-low coursing aqueducts to fill mirror-like pools, supply fountains, and irrigate the gardens.

As cultural geographer Denis Cosgrove commends the Palladian villa for its defining “coordination of all…elements into an articulated whole,” the geometries of Mughal garden design integrated different levels and lateral spaces into one overall architectural composition.[viii] Along the stone aqueducts-cum-pathways, simultaneously infrastructure and architecture, flow vital currents of water, unpredictably alive in the play of light and movement, to express complementary poetries of form, function, space, and site.

Vegetation

“The idea of the garden as something ornamental and afunctional came in with the Renaissance; the ancient world had no conception of the garden as presently understood.”[ix]

The lush vegetation of Mughal gardens provided aesthetic pleasures of color, composition, texture, and scent as well as functional habitats for wildlife, including birds, referenced in Mughal artwork and poetry, and sustaining foods and medicinal herbs. Floral motifs inspired the painting, carved and inlay detail animating the surfaces of Mughal pavilions, exteriors and interiors.

In keeping with the overall orientation of the garden as an object to be viewed from above, gardens were planted in a grid of sunken rectangles (char bagh). Sunken gardens also provided the emperor and his court entourage perambulating the stone pathways easy access to the fruits ripening on branch and vine. Leafy vegetation and the ample canopies of trees offered welcome sheltering shade from the hot sun.

Commissioned by warrior Emperors, deeply invested in their design, Mughal gardens, in their evolution from campsites to gardens and gardens to cities, functioned as seats of State, hosting affairs of court and foreign relations. The gardens were both pleasure grounds and trophies of power, affording respite from the brutality of warfare and convening eminent scholars and practitioners in science and the arts to inform and inspire the cultural life of the Imperial court. Seventeenth-century English diplomat Sir Thomas Roe records in his journal a visit with the first Mughal Emperor Babur:

…I went to court at four in the evening to the durbar, which is the place wher the Mogul sitts out

daylie, to entertayne strangers to receive petitions and presents, to give commands, to see, and to

bee seene…The place is a great court, wither resort all sorts of people. The King sits in a little

gallery over head; ambassidors, the great men and strangers of quality within the inmost rayle

under him, raysed from the ground, covered with canopyes of velvet and silke, under foote layd

with good carpetts; the meaner men representing gentry within the first rayle, the people without

in a base court, but soe that all may see the king. This sitting out hath soe much affinitye with a

theatre – the manner of the king in his gallery; the great men lifted on a stage as actors; the vulguar

below gazing on….[x]

Upon the death of the commissioner/patron, the pleasure gardens transitioned to mausoleums and funerary shrines for internment of the deceased, where solemn reverence prevailed, attended by priests and custodial caretakers.

As the Muslim culture of the Mughal conqueror assimilated into native Hindu culture, the gardens’ connection to the Yamuna River evolved to embrace traditions of both denominations. In Muslim culture, water is associated with concepts of purification:

…when a man washes his hands he must wash his heart clean of worldliness, and when he puts

water in his mouth he must purify his mouth from the mention of other than God, and when he

washes his face he must turn away from all familiar objects and toward God, and when he wipes

his head he must resign affairs to God, and when he washes his feet he must not form the intention

of taking his stand on anything except according to the command of God. Thus he will be doubly purified.[xi]

In Hindu practice, the river, Yamuna-ji, is both subject and object divine. Sacred engagement with the water is tactile and immersive:

Physical cleansing becomes emblematic of and even equivalent to moral cleansing, and one

emerges of out the water refreshed, rejuvenated, and purified. Bathing at dawn is ritually

prescribed….Life cycle events – births, tonsure, menstruation, weddings, and death –

are celebrated with a holy dip, marking the occasion and cleansing the body of pollution.[xii]

Current Conditions: Agra

Forty Mughal-era imperial gardens survive in Agra today, of which four have been restored and are open to the public under management of the Archeological Survey of India. Heritage tourism is Agra’s primary industry, yet despite its world-renowned legacy sites, including the Taj, crown jewel of Mughal gardens and the nation’s premier tourist destination, Agra ranks as one of India’s poorest cities.

The Taj, arguably Agra’s greatest strength, is paradoxically at the root of the city’s present-day challenges. In December 1996, in a bid to safeguard the Taj from corrosive industrial pollutants, India’s Supreme Court decreed the Taj Trapezium Zone, banning coke/coal industries from operating within a 10,400km-perimeter of the World Heritage Site. Agra’s manufacturing base was forced to relocate outside the city limits, drastically eliminating livelihoods for local residents without commensurate state or private sector investment in developing alternative industries or providing education or job skills retraining.

The obvious solution to Agra’s struggling economy is development of its core industry, domestic and foreign tourism. Potential in this competitive sector, however, is severely compromised by several factors, chief amongst them the desperate poverty of settlement communities that encircle Agra’s heritage monuments, presenting pockets of squalor that punctuate the overall degraded urban fabric of the city itself.

The underperformance of this vital industry locally mirrors poor and declining results for Indian tourism nationwide, an anxious trend given the sector’s vital contribution to the national economy – and a marvel, considering the extraordinary wealth of attractions in India’s culture and heritage unique to the world. Tourism contributes 6.77% to India’s Gross National Product, nearly as much as the country’s entire IT sector, which generates 7.5% toward GDP. Tourism accounts for 10.2% of national employment when direct and indirect employment are factored together.[xiii] Yet while tourism numbers continue to grow, the rate of growth is actually falling.[xiv] In the case of Agra, rising tourism numbers reflect an increase in domestic over foreign visitors, who generate less revenue per visit than international tourists through lower entrance fees and shorter stays. The construction of the Yamuna Expressway, completed in 2012 and intended to promote Agra tourism, inadvertently undermines the city’s overall economy by making it possible to visit heritage sites in a four-hour round trip from Delhi, de-incentivizing stays of longer duration that would support local hotels, restaurants, and retail. Instead, visitors engage in one-stop viewing, touring the Taj, perhaps other lesser-known, less-visited yet illustrious Agra heritage monuments – I’Timad-ud-Daulah, tomb of Mirza Ghiyas Beg, minister of Emperor Akbar and father of Nur-Jahan (introduced below) and grandfather of Mumtaz-Mahal (for whom the Taj is namesake), or Akbar’s tomb, Sikandra – and departing.

Incidents of high-profile violent, sexual assault and a general perception of crime further degrade India’s desirability as a tourism destination, disproportionately adversely impacting Agra, given its dependence on tourism revenue. The chronic poverty of slum communities, an unavoidable presence at Agra heritage monuments, exacts a heavy toll. Imagine, by comparison, approaching Buckingham Palace threading narrow alleys lined with open sewers, overcrowded shanty houses, being accosted by mothers with infants and vagabond children begging in the streets. Throngs queued for London’s tourist mecca would reasonably thin. To perceptions of a lack of safety and the actual and prevalent conditions of abject poverty, aggravated health concerns – dissuading visitors from drinking anything but bottled water and warned off eating local food – further insulate foreign guests from the ad hoc, street-level experiences of place that motivate travel and build the enduring bonds that yield repeat visits and expanded networks for years to come. In this challenging context, gathering global headlines broadcasting the escalating toxicity of India’s environment deliver a coup de grâce.

Incidents of high-profile violent, sexual assault and a general perception of crime further degrade India’s desirability as a tourism destination, disproportionately adversely impacting Agra, given its dependence on tourism revenue. The chronic poverty of slum communities, an unavoidable presence at Agra heritage monuments, exacts a heavy toll. Imagine, by comparison, approaching Buckingham Palace threading narrow alleys lined with open sewers, overcrowded shanty houses, being accosted by mothers with infants and vagabond children begging in the streets. Throngs queued for London’s tourist mecca would reasonably thin. To perceptions of a lack of safety and the actual and prevalent conditions of abject poverty, aggravated health concerns – dissuading visitors from drinking anything but bottled water and warned off eating local food – further insulate foreign guests from the ad hoc, street-level experiences of place that motivate travel and build the enduring bonds that yield repeat visits and expanded networks for years to come. In this challenging context, gathering global headlines broadcasting the escalating toxicity of India’s environment deliver a coup de grâce.

Current Conditions: Ram Bagh and Zahara Bagh

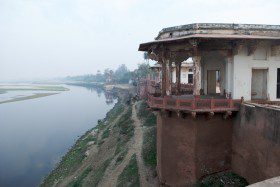

India’s first Mughal ruler, Babur, completed Ram Bagh, Agra’s first imperial riverfront garden, sited on the east bank of the Yamuna, in 1528. Extensive surveys undertaken from 1978 to 1986 by Austrian architectural historian Ebba Koch reveal garden artifacts dating from 1621. This indicates that Babur’s original Ram Bagh continued to be revised and was actually completed by Nur Jahan, wife of Emperor Jahangir, Babur’s great-grandson, marking a notable occasion of female architectural patronage in the Imperial court. Adaptation of the garden continued through British colonial rule, during which period a second story was added to the riverfront pavilion and the garden served as a leisure setting for picnics and honeymoons. In its most recent iteration, Ram Bagh has been formally reconstructed and is open to the public primarily as a museum of Mughal-era garden architecture catering to out-of-town domestic and foreign clientele. Locally, Agra’s middle-class residents frequent the garden seeking midday refuge from the hot, congested city.

Present-day Ram Bagh retains the green lawns introduced by the British, which replaced the orchards and flora of the original design. Its formal restoration, jointly undertaken by the Archeological Society of India (ASI) with the World Monuments Fund (WMF), offers an exemplary representation of the Mughal char bagh template: clear geometries established by raised stone walkways, water channels, mirror pools, a-symmetrically positioned waterfront palaces (as noted also in the garden of Khan-i-Alam, to the North of the Taj, now a nursery for Taj flowers), wells, cisterns, angular chattri, including a perimeter wall that partitions the noble precinct from common grounds.[xv] An adjacent, dilapidated oblong area, functioning as a cattle yard since 1923, presents an interesting extra-moenia feature of the garden, surrounded by arcades and square cells (hujar), which are used for bazaars, and is accessible by gates to the east and west.

In a survey conducted in 1871-72 by British archeologist Archibald Carlleyle, appointed by the ASI, Carlleyle cites several structures at the garden that are now lost: a main courtyard building on the riverfront supported by a substructure with sunken vaulted rooms that opened onto the river and connected to a tank. The pavilion opened at the center of each side. Two flights of stairs joined the platform in front of the subterranean rooms, leading to the river. The walls enclosing the garden were visible, with the front wall measuring 376 x 333 meters; the entrance gate was centered in the side landward wall, and connected to the palace by a paved walkway punctuated with platforms. A large octagonal tank occupied the northeast corner.

In a survey conducted in 1871-72 by British archeologist Archibald Carlleyle, appointed by the ASI, Carlleyle cites several structures at the garden that are now lost: a main courtyard building on the riverfront supported by a substructure with sunken vaulted rooms that opened onto the river and connected to a tank. The pavilion opened at the center of each side. Two flights of stairs joined the platform in front of the subterranean rooms, leading to the river. The walls enclosing the garden were visible, with the front wall measuring 376 x 333 meters; the entrance gate was centered in the side landward wall, and connected to the palace by a paved walkway punctuated with platforms. A large octagonal tank occupied the northeast corner.

Today, the walls to the north lay in fragments, the platform having fallen into the Yamuna, leaving its supporting cylindrical wells still visible. The southeast chattri, clad in red sandstone, is relatively well preserved, along with many notable decorative features (floral chini-kana and niches). Other structural elements survive: two garden pavilions in the form of chattris, and a vaulted hamman complex along the exterior north wall. Although in fairly good condition, they are not mentioned by Carlleyle, suggesting that this part of the garden was likely covered in thick vegetation, with only the riverfront access in use. Photographs dating from the second half of the nineteenth century document riverside livelihoods of fabric washing and dyeing.

Waterworks underground and embedded in the raised stone pathways are dormant, the surface channels empty. In a 1974 Dumbarton Oaks conference, garden scholar Susan Jellicoe suggested that water in the Mughal garden “is perhaps even more important than soil…. The soil is static, as is the stonework, while the water and the plants are kinetic, but in the garden their relationship becomes symbiotic.”[xvi] The acute water shortage of present-day Agra severs this intimate connection of stone and water, soil and plant. The garden’s thirst is a dry wound.

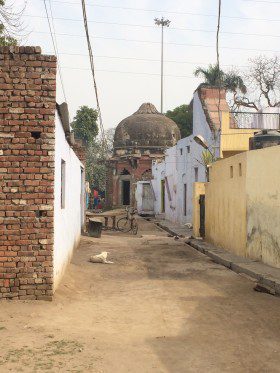

Neighboring Ram Bagh is a settlement community established on the grounds of another imperial Mughal garden, Zahara Bagh. Commissioned by Mumtaz Mahal, (d. 1631), favorite wife of Emperor Shajahan, who built the Taj, folklore tells, to commemorate her death in childbirth delivering their fourteenth child, Zahara Bagh was completed in 1621. The garden’s provenance of contemporaneous female patronage underscores the historic connection between Zahara Bagh and the adjacent Ram Bagh, whose imperial patron was Empress Nuh Jahan. On her death, Mumtaz bequeathed the garden to her daughter Jahanara, furthering continuity in the rare lineage of female courtier garden patronage.

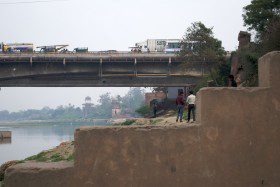

Today, the heritage of the garden is largely submerged, save ruin fragments scattered throughout the site. Despite its illustrious past, Zahara Bagh was never under ASI protection and ownership, which allowed construction of the National Highway No. 2 bypass to cut off its northern edge, disaggregating the garden ruins. In contrast to the formal, museum reconstruction of Ram Bagh, Zahara Bagh hosts an informal residential community, whose livelihoods derive from commercial nurseries constructed within the former noble precincts. Authentic to the heritage of Mughal-era Agra, the new-century industry of Zahara Bagh is gardens. Shrines erected on the banks of the Yamuna attest to the active spiritual connection of community and river.

The riverfront of Zahara Bagh has transformed dramatically. The hard edge of Mughal design is disintegrated and populated by a fragmented constellation of small architectural symbols of religious worship. Three sets of stairs (shri ram ghat) connect the garden level to the water, which become submerged in part during monsoon rains. No longer represented in the Islamic tradition as a framed object within a distant picturesque background, the garden setting now fully embodies Hindu tradition, with the river easily accessed for sacred ritual as well as recreation as community children repurpose stairs and ruined Mughal platforms as diving boards during the rain-swollen monsoon season.

The riverfront of Zahara Bagh has transformed dramatically. The hard edge of Mughal design is disintegrated and populated by a fragmented constellation of small architectural symbols of religious worship. Three sets of stairs (shri ram ghat) connect the garden level to the water, which become submerged in part during monsoon rains. No longer represented in the Islamic tradition as a framed object within a distant picturesque background, the garden setting now fully embodies Hindu tradition, with the river easily accessed for sacred ritual as well as recreation as community children repurpose stairs and ruined Mughal platforms as diving boards during the rain-swollen monsoon season.

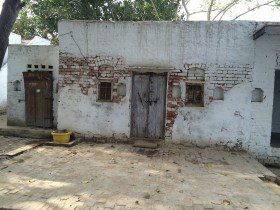

Although illegally constructed, the dwellings of the residential village are well kept and established. Open-channel, brick sewers collecting wastewater service some of the houses; others, however, at the margins of the settlement are in more precarious state. Overall, the village conforms to the standard, inadequate conditions of informality, lacking self-sufficient hygiene, healthcare, education, and amenities.

Nurseries constitute the main commercial activity on site, with a few small, independent workshops visible through the open doors of village houses. Plants cultivated on the extensive grounds are sold in shops along the nearby road leading to the center of Agra. Street florists offer an array of species – flowers, fruits, ornamental and native plantings – advertised in colorful banners announcing: “Government Nurseries.” The website “Hindustan Nursery” provides specialty goods and services nationally: farmhouse, gardening, landscaping, ayurvedic plants, and government supplies.[xvii] The seller for Zahara Bagh, Sunita Farm & Nursery, has an active and comprehensive website. Names of the owner and branch manager are posted with images of the nursery and a brief narrative history marking the planting of eucalyptus in 1970 as the date Zahara Bagh became a “nationally recognized 4-acre garden.”[xviii] Operations are expanding. In 2013, the website posts, the present owners turned a carrot field and semi-wooded, overgrown area of shrubs into new fields for commercial cultivation.

Water for irrigation of the nursery beds is largely collected from the Yamuna. Pumps installed proximate to the old brick towers draw water to ground level (a few meters above the river) to fill small pools that drain into open brick channels and flow to the garden beds – a system reminiscent of Mughal-era waterworks. New tanks have been installed adjacent to a defunct Mughal well, appropriating and adapting the historic infrastructure.

Zahara Bagh functions today as an almost holistic community: living, praying, and working in the former imperial garden. Repurposed Mughal-era artifacts and the geometry of the cultivated ground are organized in quadrants as if following invisible historical traces. Yet, while a vibrant working community has stabilized a way of life – albeit at fragile, subsistence level – one appropriately questions, “At what cost?” Crude adaptive re-use of Mughal remains, modern irrigation methods that compromise the integrity of legacy infrastructure, inefficiently tapping the already-exhausted Yamuna – is too much lost in the cultural and ecological system of the heritage site?

“Not only the thirsty seek the water, the water also seeks the thirsty.”[xix] The catalytic thirst that initiated Mughal garden practice, namely Babur’s longing for the landscape of his youth – an attachment of sentiment and identity – prevails and drives the quest for meaning in the 21st-century death and life of Agra’s riverfront gardens. Attention to the complex systems they exquisitely composed – physically, in their superb stone geometries; technologically, in their masterful mechanisms for water capture, containment, and distribution; productively, in their garden harvest; culturally and politically in their social performance – offers insight into recuperating sustaining vitality for these two complements of garden practice, the museum garden and the settlement garden, while providing India as a nation a global platform to debut new leadership in progressive social reform and environmental stewardship.

“Not only the thirsty seek the water, the water also seeks the thirsty.”[xix] The catalytic thirst that initiated Mughal garden practice, namely Babur’s longing for the landscape of his youth – an attachment of sentiment and identity – prevails and drives the quest for meaning in the 21st-century death and life of Agra’s riverfront gardens. Attention to the complex systems they exquisitely composed – physically, in their superb stone geometries; technologically, in their masterful mechanisms for water capture, containment, and distribution; productively, in their garden harvest; culturally and politically in their social performance – offers insight into recuperating sustaining vitality for these two complements of garden practice, the museum garden and the settlement garden, while providing India as a nation a global platform to debut new leadership in progressive social reform and environmental stewardship.

Vision: Toward a Living Heritage

In the February 2015 workshop jointly hosted by the ASI and Harvard University, culminating fieldwork in Agra conducted by students at the Graduate School of Design, there was broad-based agreement that historic preservation in India must evolve from its emphasis on the heritage monument as a static object to one more inclusively integrating local communities. A primary goal identified and explored embraces the notion of a living heritage, a “people’s heritage,” bridging past and future to achieve a more vibrant and sustaining present. The physical adjacency and intertwined histories of Ram Bagh and Zahara Bagh recommend these two heritage gardens as reciprocal test case studies to pilot new strategies at the intersection of progressive preservation and community development.

The vision sketched below builds on the achievement of the ASI and WMF in their exacting thirty-year formal restoration of Ram Bagh preparing an extraordinary stage on which to invent the garden’s twenty-first-century leading role. It also looks to and embraces the vitality of the settlement community living, working, and worshipping in the former royal grounds of Zahara Bagh, a social performance that has lacked a formal frame. Historically, Mughal gardens were potent settings politically and culturally: emblems of power; citadels of art, science, and technology; shrines and temples of faith. Recuperating their historic function of performance and engagement, new integrated identities are proposed for the museum garden, Ram Bagh, and the settlement garden, Zahara Bagh, that develop their complimentary roles as “heritage destination” and “heritage in practice.” Three strategies for innovative preservation are explored through themes of (1) water [restoration and management] and vegetation [heritage, commercial, and R&D]; (2) digital conservation; and (3) community education/vocational training in hospitality, botany, history and art history.

Water and Vegetation

In the closing chapter of Towards Water Wisdom: Limits, Justice, Harmony, author Ramaswamy R. Iyer implores the reader, “The world has changed; let our thinking change.”[xx] Though sharing in and supporting the spirit of his argument, we invert his invocation, “The world has not changed; let us remember.” Water plays a significant role in the success of social spaces, notes American sociologist William H. Whyte in his iconic study, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces – the look, the sound, and the feel of it. A primary objective of the proposed revitalization of the heritage gardens is to restore and foreground this essential feature. In Ram Bagh, this would entail reviving the Mughal-era waterworks systems, integrating as needed new technologies, healing the dry wound of the thirsty garden and reconnecting the symbiotic relationship Jellicoe identified between static stone and soil and kinetic plants and water.

In the closing chapter of Towards Water Wisdom: Limits, Justice, Harmony, author Ramaswamy R. Iyer implores the reader, “The world has changed; let our thinking change.”[xx] Though sharing in and supporting the spirit of his argument, we invert his invocation, “The world has not changed; let us remember.” Water plays a significant role in the success of social spaces, notes American sociologist William H. Whyte in his iconic study, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces – the look, the sound, and the feel of it. A primary objective of the proposed revitalization of the heritage gardens is to restore and foreground this essential feature. In Ram Bagh, this would entail reviving the Mughal-era waterworks systems, integrating as needed new technologies, healing the dry wound of the thirsty garden and reconnecting the symbiotic relationship Jellicoe identified between static stone and soil and kinetic plants and water.

Adapting models of teaching museums such as the Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, the MIT Museum at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Harvard’s Dumbarton Oaks; and botanical gardens (New York and Boston, for instance) and research institutions (Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences at Alnarp), Ram Bagh would host working exhibitions of Mughal water systems, demonstrating the application and interpretation of the “old wisdom” for present-day practice and future conservation. These systems would be recuperated, as possible, and installed in the commercial nurseries in Zahara Bagh in the effort to stabilize and optimize production for current and anticipated climate adaptation, thus showcasing commercial application of historic and hybrid twenty-first-century water management. Tours would be offered for visitors to study the water management systems on view and operational in the historic setting of Ram Bagh and their expanded implementation at work in Zahara Bagh.

Landscaping at Ram Bagh would be revised to feature water-efficient native plantings and adaptive strategies such as swept earth ground treatment rather than the water-hungry green lawns introduced during British rule.[xxi] A sample heritage garden would be planted and maintained as a permanent exhibition providing a portal in time to the original Mughal-era gardens. A comparable project, installed in New York City in 1978, “Time Landscape,” by artist Alan Sonfist, recaptures New York’s native forest before the arrival of Dutch settlers in the seventeenth century, affording visitors and residents a connection to New York’s virgin terrain.[xxii]

Digital Conservation

As part of on-going restoration and maintenance, conservation laboratories would be set up on-site at Ram Bagh introducing state-of-the-art conservation technologies currently developing at research institutes such as the Architectural Conservation Lab, Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD). The “Heritage Building and Digital Tectonic” project, led by SUTD assistant professor Dr. Yeo Kang Shua, designs digital models for the “undrawable architecture” of Yueh Hai Ching temple (1895) as its pilot study, with the goal of producing comprehensive preservation documentation for the artisan handwork that was never rationalized but handed down generation to generation. Efforts to develop twenty-first-century digital methods of reconstructing the labor-intensive handwork safeguard centuries-old heritage practices as skilled artisans age and fewer and fewer apprentices take up the trade. These investigative research and design methodologies could be applied toward modeling the lost architecture of Zahara Bagh without displacing the settlement community.

From this base of digital conservation, satellite training programs and facilities would be encouraged to introduce new technologies to other key Agra handcrafts such as embroidery and carving. Old traditions can be protected, adapted, and thrive in the emerging economies of 3D printing and robotics.

From this base of digital conservation, satellite training programs and facilities would be encouraged to introduce new technologies to other key Agra handcrafts such as embroidery and carving. Old traditions can be protected, adapted, and thrive in the emerging economies of 3D printing and robotics.

Community Education/Vocational Training

Education initiatives for the Ram Bagh/Zahara Bagh collaboration envision partnerships with universities and research and training institutes. A primary partnership is proposed with Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University (formerly Agra University) to anchor local education and skills training in three core sectors: hospitality, botany, and history.

Community Education: Hospitality

The opportunity for development in Agra’s tourism industry is almost without bounds. Compelling precedent is found in the small Swiss alpine village of Vals, whose municipality commissioned Swiss architect Peter Zumthor to design a thermal baths resort complex, which reversed and stabilized the faltering fortunes of the struggling community. The success of Therme Vals, now operating as Therme 7132, derives from the clarity of its mission to curate the alpine tourism experience.[xxiii] Building on its “brand” of clean air and ancient thermal waters, Therme 7132 has established itself as a stylish temple of wellness, with hotel revenue ranging in rate from US$150 to $600 a night. The complex, currently expanding, has two new facilities under construction, designed by preeminent Pritzker-Prize-winning architects Thom Mayne and Tadao Ando.

As seat to numerous World Heritage sites, the point here is not to promote community development in Agra through architectural commissions – though the opportunity will come – rather the agenda is to identify and define Agra’s mission “to curate the Heritage tourism experience” to world-class standards commensurate with its world-premier heritage. Education and training in the fundamentals of tourism is the start. A Center for Heritage Tourism could be jointly administered with the Institute of Hotel and Tourism Management, founded in 2004, at Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University, developing curriculum and providing training for Agra residents. While air quality ranking Agra 19th on WHO’s 50 Most Polluted Cities would thwart initiatives to revive the heritage garden identity as paradise oases, India’s ancient practices of yoga and meditation, if conducted in rooms with superior air filtration, could be a signature supplement to Agra’s heritage tourism and relate to the garden’s former function as shrines and sites of worship.

Community Education: Botany

Another potential partnership between Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University and the Ram Bagh/Zahara Bagh collaborative project is study and training in botany, administered through the University’s School of Life Sciences, founded in 1998. External cooperation in the life sciences with international universities such as Harvard University, Cornell University, SUTD, and the Swedish University for Agricultural Sciences, might also be pursued. Fieldwork would be conducted on site at Ram Bagh in living labs to include biotech research on plant adaptation for climate change and water scarcity as well as research into historical flora.

Community Education: History

As a living heritage, Ram Bagh and Zahara Bagh regain their performative function as active sites of scholarship and research. Community residents train as docents to conduct tours on Mughal history, the arts and architecture, science and technology, both historical and contemporary systems on view in Ram Bagh, museum garden as laboratory, and in practice at Zahara Bagh, the live/work settlement garden. From royal precincts to community resource, the achievement of the Mughal gardens as sites of beauty, power, and scholarship is not only honored but performed: new players, old stories, new applications, old wisdoms, new life.

Conclusion

Successful social places are places people want to be, not just places people want to see. India’s underperforming tourism sector reflects an industry-wide decline in spectator tourism globally. In the U.S., by example, museum attendance has been on the decline pre-dating the 2008 economic collapse that curtailed disposable income expenditures on leisure travel and entertainment. Despite growth in the U.S. population between 2009-13, a survey of U.S. Nonprofit Visitor-Serving Organizations (museums, science centers, historical sites, aquariums, zoos, symphonies) reported flat or declining attendance.[xxiv] Having something to see, “shopping with your eyes,” may be a necessary criterion for leisure travel expenditure, but it is apparently no longer sufficient.

Identifying four key attributes of successful places, the Project for Public Places, New York, cites: accessibility, positive image, uses and activities, and sociability.[xxv] Mughal gardens, while showcases of splendor and trophies of power, were historically purposeful platforms for politics, scholarship, art, technology, science, and worship. Through inventive preservation strategies that restore the function as well as the form of the legacy gardens, adapted for contemporary relevance as they have adapted throughout history, India has the opportunity, on her own terms, through an illustrious heritage that has captured the wonder of the world for centuries, to demonstrate urgently needed leadership in social reform and environmental stewardship. India’s old wisdom is the new wisdom. In so doing, Mughal riverfront gardens are not only restored, they are alive, not only places to see, but again glorious places to be. – Let the world headline this.

Photos, unless otherwise noted, courtesy of Jane Philbrick and Maria Letizia Garzoli.

[i]World Health Organization, World’s 50 Most Polluted Cities, 2014; http://www.who.int/phe/health_topics/outdoorair/databases/cities/en/

[ii]Deepshikha Sharma and Arun Kansal, “Current Condition of the Yamuna River – An Overview of Flow, Pollution Load and Human Use,” TERI University, Delhi, India. “Yamuna River: A Confluence of Waters, a Crisis of Need,” The Forum on Religion and Ecology at Yale: Yale-TERI Workshop on the Yamuna River, January 3-5, 2011.

[iii] Gardiner Harris, “Holding Your Breath in India.” The New York Times, May 31, 2015, p. SR1.

[iv] Penelope Hobhouse, Erica Hunningher, Jerry Harpur, The Gardens of Persia. Carlsbad, California: Kales Press, 2004, p. 82.

[v] Annette P. Beveridge, trans., Baburnama in English, London, 1912-22, fasc. 3., p. 532.

[vi] Vikram Soni, Shashank Shekhar, Diwan Singh, “Environmental Flow for Monsoon Rivers in India: The Yamuna River as a Case Study”; http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1306/1306.2709.pdf

[vii] http://agricoop.nic.in/dacdivision/machinery1/chap7.pdf

[viii] Denis Cosgrove, “Villa: The Palladian Rural Landscape,” in The Palladian Landscape: Geographical Change and Its Cultural Representation in Sixteenth-Century Italy. Philadelphia: Penn State University Press, 1993.

[ix] James Dickie, “The Mughal Garden: Gateway to Paradise,” in Muqarnas, Vol 3 (1985), p. 132.

[x] Sir Thomas Roe, The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to the Court of the Great Mogul, 1615- 1619, as Narrated in His Journal and Correspondence. London: Hakluyt Society, 1899, pp. 84-86.

[xi] Reynold A. Nicholson, trans., Kashf al-Mahjub: “The Revelation of the Veiled,” An Early Persian Treatise on Sufism. London: E.J.W. Gibb Memorial Trust, 1911, p. 329.

[xii] Amita Sinha and D. Fairchild Ruggles, “The Yamuna Riverfront, India: A Comparative Study of Islamic and Hindu Traditions in Cultural Landscapes,” in Landscape Journal, Vol. 23, Issue 2 (2004), p. 144.

[xiii] Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, “Tourism contributes about as much to India’s economy as the entire IT sector,” Quartz, August 7, 2014; http://qz.com/246377/tourism-contributes-as-much-to-indias-economy-as-the-entire-it-sector/

[xiv] Aditya Dev, “Foreign Tourism at Taj Down,” The Times of India, January 2, 2015; http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Number-of-foreign-visitors-to-Taj-Mahal-on-wane/articleshow/45723601.cms

[xv] Lucy Peck, Agra: Architectural Heritage. Delhi: Roli Books Private, Limited, 2011.

[xvi] James Dickie, “The Mughal Garden: Gateway to Paradise,” in Murquas, Vol. 3 (1985), p. 130.

[xvii] http://hindustannursery.com/

[xviii] http://sunitafarmnursery.com/garden/garden.html

[xix] Annemarie Schimmel, “The Water of Life,” in Environmental Design 11 (1985), p. 9.

[xx] Ramaswamy R. Iyer, Towards Water Widsom: Limits, Justice, Harmony. New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2007, p. 240.

[xxi] James L. Wescoat Jr. (2013) The ‘duties of water’ with respect to planting: toward an ethics of irrigated

landscapes, Journal of Landscape Architecture, 8:2, 6-13, DOI: 10.1080/18626033.2013.864070; p. 11.

[xxii] Alan Sonfist, “Time Landscape,” New York: Public Art Fund, 1978 – present.

[xxiii] John Caulfield, “Morphosis unveils plans for controversial high-rise hotel in tiny Alpine village,” March 27, 2015; http://www.bdcnetwork.com/morphosis-unveils-plans controversial-high-rise-hotel-tiny-alpine-village#sthash.WhZu581R.dpuf

[xxiv] “Signs of Trouble for the Museum Industry (Data),” December 3, 2014; http://colleendilen.com/2014/12/03/signs-of-trouble-for-the-museum-industry-data/

[xxv] Matthew Carmona, Tim Heath, Taner Oc, Steve Tiesdell, Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design. Oxford, England: Architectural Press, 2003, p. 100.