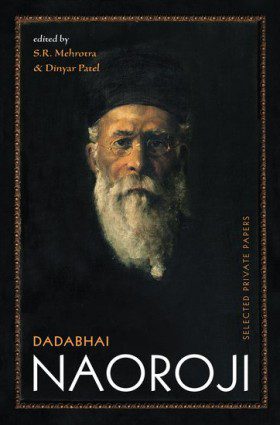

Dinyar Patel, currently an Assistant Professor at the University of South Carolina, completed his PhD at Harvard and was previously a SAI Graduate Student Associate. His Harvard dissertation focused on the political thought of Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917), perhaps the most prominent Indian nationalist figure prior to Mohandas K. Gandhi. With S.R. Mehrotra, he recently co-edited a volume of selected correspondences from the Dadabhai Naoroji Papers, which was published by Oxford University Press over the summer. Many of the over 500 letters have never been published before.

Dinyar Patel, currently an Assistant Professor at the University of South Carolina, completed his PhD at Harvard and was previously a SAI Graduate Student Associate. His Harvard dissertation focused on the political thought of Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917), perhaps the most prominent Indian nationalist figure prior to Mohandas K. Gandhi. With S.R. Mehrotra, he recently co-edited a volume of selected correspondences from the Dadabhai Naoroji Papers, which was published by Oxford University Press over the summer. Many of the over 500 letters have never been published before.

SAI recently spoke to Patel about the project and why Naoroji is still so relevant today.

SAI: Why are these writings so important?

Dinyar Patel: This individual, Naoroji, kept in his collection as many as 50,000 documents, but only about 30,000 have survived up until today. What the collection ended up being was a lot of letters exchanged with prominent Indian and British political figures of the time. A lot of these figures are not terribly well-remembered in either country, but at the time they were leading political figures. For example, a socialist leader named Henry M. Hyndman exchanged a lot of colorful letters with Naoroji about socialism in Great Britain, Europe, and India. There were letters exchanged with people such as William Wedderburn, who was one of the founders of the Indian National Congress along with Naoroji. Both of them would talk about the need for political reform in India, and specifically, the need for Indians to contest parliamentary elections in Great Britain in order to reform India from within.

SAI: Is there a letter or document that really surprised you in some way?

DP: There were a lot of letters from people who have been categorized in history as being not terribly radical or not too sympathetic towards self-rule in India. That’s the common understanding of who these people were. When you actually go and read a lot of these letters, you discover that that’s not necessarily true. A lot of them had very radical views.

To give you an example, the person who founded the Indian National Congress was a man called Allan Octavian Hume. He was a Scotsman, he was actually from Britain, but he was very sympathetic towards Indian political concerns. A lot of historians have said he was kind of a fifth column for the British, and he established the Congress to try to protect the Raj, which is completely untrue, and historians have pointed to this recently. But if you read his letters, you see that towards the end of his life, he was saying that perhaps the best things for Indians to do to get rid of British rule is violent overthrow of the government, which is something that no one has really talked about before. Everyone thought he was too moderate to suggest something like that. However, here he’s openly saying that the best thing might be violence. Stuff like this is what really makes the collection important.

SAI: I know you did a lot of archival research. What was that like, to physically go through the letters and documents?

DP: It was a lot of fun for me. Most of the collections I looked at were in New Delhi in the National Archives of India. It can be difficult to work in places such as that. Conditions are not as good as London, or Washington DC, or Boston. There are issues with preservation. There are problems, but because so few people have looked at these documents, there is so much new stuff to explore. Every time you go in, you are reading documents that hardly anyone has looked at before and you’re finding all sorts of new and exciting things.

I was back there in August for just a few days, and I found a letter written by one of Naoroji’s daughters, where she’s talking about how the first bicycles were introduced into Bombay and the fact that some women were actually riding these bicycles, which was relatively revolutionary at the time, regardless of where you were in the world.

SAI: You’ve spent a lot of time with Naoroji – what was it that initially drew you to him and sparked your interest?

DP: People like him have been relatively forgotten in comparison to other political leaders in both India and Great Britain. So much so, with Naoroji at least, that the last good biography of him was done in 1939, which is a long time for historians. Every few years there are biographies coming out about Gandhi. That was something that really interested me about Naoroji. And knowing that there were all these letters sitting in Delhi that no one had really looked at for a very long time. I thought it was high time to look at these individuals and give a new perspective on them. A lot of historians have written them off as being stooges of the colonialists, or people who didn’t matter that much or accomplish much.

SAI: What can historians learn from Naoroji?

DP: The biggest lesson is just the importance of doing really thorough archival research. It’s so difficult to reconstruct these people’s lives, and when we only look at a few published documents, we only get a partial picture. But when you start to look at letters and the like you get a much broader and complex picture that in many ways change what you think of these people.

When you read these letters, especially letters that are not in English, you find so much that alters your perspective, not just on the history of India, but on the history of the British Empire or even entire movements like anti-colonialism.

SAI: As a historian, you think about the past. But what kind of impact or parallels do you see for today, for India or the world, when you’re studying Naoroji?

DP: People like Naoroji were talking about a lot of similar issues to what politicians are talking about now in India: corruption, and poverty, which was by far the biggest issue that concerned Naoroji. For the past 20 years, the dynamic of political debate in India has revolved around economic reform. Naoroji was ultimately concerned about the fate of the average man living in India, who was mostly likely living as a rural agricultural worker. He looked at what was happening to people like them, and during the course of his political life, anywhere from 30 million upwards people died in India because of famine. These were famines that could have been avoided had the British done more at the beginning to stem the loss. He was ultimately concerned with the poorest of the poor.

A lot of the debate in India right now has focused on something similar: should we be concerned more about economic liberalization, should we somehow compensate free market reform policies that also involve redistribution of wealth, so as to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor in India. There is a lot of relevant stuff to talk about.

In general, the thrust of his political work was anti-colonial, so he would talk about how particular imperial policies were crafted for the self-interest of the people who ruled. Which, if you take out of the dynamic of imperialism, it’s very similar to what we’re talking about right now with economic issues in America or Europe: distribution of wealth, distribution of power, who holds political power.

SAI: Do you have any ideas for projects in the future?

DP: By being in South Carolina, it’s been interesting to see some comparisons between the history of the American South and places like India, in terms of agricultural dependence, cash crops like cotton, and then of course racial dynamics. It has been interesting to talk to historians over here [South Carolina], who study the American South – that is something I’d like to explore further.

SAI: You mentioned Ben Franklin before. Is there a good equivalent in American history to compare with Naroroji?

DP: Franklin is who I would make Naoroji most equivalent to, and even in his time he was thought of by some people as the “Ben Franklin of India.” Ben Franklin lived through the period where America got its independence. However, Naoroji died well before India did. That’s the major difference. But like Franklin, he was a very senior statesman who helped to get the ball rolling, and helped enunciate a lot of the particular political and economic grievances that people had.

Oxford Press: Dadabhai NaorojiSelected Private Papers

This interview has been edited for clarity and length

-Meghan Smith