By Meghan Smith, Communications and Outreach Coordinator, SAI

By Meghan Smith, Communications and Outreach Coordinator, SAI

Sometimes, to shatter the glass ceiling, you need a weapon.

Rachel Parikh has plenty at her fingertips – and she wants to use them to break more than a few glass ceilings. As the Calderwood Curatorial Fellow in South Asian Art at Harvard Art Museums, she focuses her work on manuscripts, arms, and armor – yes, weapons.

She admits that even she had her own misconceptions about studying weapons.

“You often associate arms and armor with war, violence, and masculinity,” Parikh says. “I made my own PhD dissertation all about breaking misconceptions about Islamic art and South Asian art, so it was funny that I fell into this misconception about arms and armor.”

Parikh’s dissertation at the University of Cambridge focused on a seventeenth century Deccan Indian copy of a sixteenth century Persian manuscript called the Falnama (‘Book of Omens’). After completing her Ph.D. Parikh was a Postdoctoral Fellow at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, where she researched and cataloged objects for the museum’s Department of Arms and Armor.

The number one rule of working in that department at the Met? Don’t bleed on the art. Parikh says she has been lucky to not have hurt herself – only a cut on a glove here and there.

Arms and armor, as an art history discipline, deals with a wide variety of objects: Edge weapons like swords and daggers; firearms like rifles and pistols; staff weapons such as clubs, spears, and javelins; archery equipment; and protective gear like breastplates and linked metal shirts. Besides war, they were used for diplomatic relations, courtly processions, as fashion trends, as jewelry, in ceremonies and religious rituals, and hunting.

“I was blown away by not only how beautiful these objects are, but how they represent more than war and battle,” Parikh says. “There is this humane aspect to war that we tend to forget about when we look at these materials.”

Women, especially in South Asia, had their own uses for weapons. Especially under the Mughals in Rajasthan, women practiced archery and participated in royal hunts. They mounted horses with bows and arrows, showcasing their grace and skill. Accessories displayed their wealth, rank, and status.

Despite the fact that art history is a popular subject for women to study, as a professional field it is still largely dominated by men, including at the Met. Only a handful of women in the art world study weapons.

“As a woman, it’s very empowering to work on this material,” Parikh says. “Now I’ve made it my research mission to break these misconceptions. It’s good to shake things up a little bit.”

Parikh does not want this research to be stuck in the past, either. She points out that shows like Game of Thrones, HBO’s fantasy drama series that has become a cultural phenomenon, are getting people to pay attention.

“I have to sometimes watch an episode twice – the first time I’m watching it just for pure enjoyment, and the second time I’m actually watching what they are wearing or carrying,” Parikh says, with the enthusiasm of a dedicated fan. “A lot of the weapons are developed from European materials, but non-Western inspirations are also being drawn in, which I find fascinating. They [the producers] do their research.”

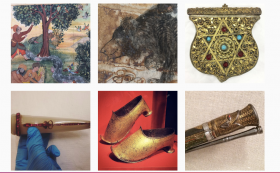

At Harvard, Parikh’s current project is helping the museum catalog its extensive South Asian art collection, made up of about 1500 objects. The Museum hopes to make the collection accessible to the public on its website.

Parikh spends her days studying each object by hand and deducing as much information as possible based on her own knowledge and language skills – she reads Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit, and Hindi. She has many moments which she has dubbed her ‘pinch me moments.’ She was recently working on a manuscript that belonged to the Mughal emperor Akbar, who reigned from 1556 to 1605 and is considered one of the most powerful rulers of the Indian subcontinent.

“I’m holding a manuscript that is centuries old that was commissioned and held by one of the most powerful rulers of the early modern world,” Parikh says. “It was preserved in his library, and now it is preserved at Harvard. It blew my mind.”

When asked which is her favorite object in the collection, she pauses and looks up at the sky – clearly, not an easy question to answer for someone so passionate about her work. She settles on a lacquered shield, decorated with lions gilded in gold. It was never used in the battlefield.

Parikh just submitted a manuscript for her first book, what she calls a “foundational” text on South Asian art and armor. Little scholarship currently exists on the subject, so she hopes to inspire more people to follow her lead.

Parikh runs an Instagram account (@rachel.parikh) to share some of her favorite finds from her work. “The more people I can reach out to, to help them understand and appreciate these objects, particularly the ones that come from South Asia, I consider to be a particularly rewarding experience.”