Whenever my Pakistani family and acquaintances discuss the original ‘Brexit’, the 1947 transfer of governance to the new states of India and Pakistan, we mostly talk about communal tensions among Hindu, Muslim and Sikh communities, or focus on contemporary political shenanigans in the region. Though most branches of my family were directly affected by the events of 1947, we rarely discuss its personal and familial impact. This interplay of easy conversation and silences around the Partition is a trope in the inheritances of history and family mythology in many Pakistani and Indian families.

The academic industry around Partition, however, has recently begun to understand that individual and social experiences, as Ilyas Chattha says, are “Partition history’s integral subject, not just its by-product or an aberration”.

We learn more about this world-changing event from the stories of men, women and children who were not in the top tiers of the Muslim League or Indian National Congress parties whose history has come to define this seminal event in the world’s memory.

As a researcher on The Mittal Institute’s collaborative Partition project, my goal has been to find and understand several pairs of opposites – care and violence, survival and death – as they co-existed in South Asia immediately before and after August 1947. In this massive, under-documented humanitarian episode, the ‘human’ element needs to be better represented in all its complexity.

The echo chambers of nationalism present a challenge in developing a three-dimensional model of how the millions of people were affected by Partition, making it harder to conceptualize a true ‘people’s history’. A significant portion of this historiographic focus, certainly in the English language, has been on what would become ‘Indian’ stories, for a variety of reasons.

In the case of Pakistan, at least, the archives that could give shape to a subaltern narrative are lost, scattered or obscured behind concentric circles of privacy, without a will to even look. The country’s fledgling bureaucracy, as well as citizenry, lacked the pre-existing infrastructure and wealth that existed across the border, resulting in a relative flattening of Partition narratives in circulation.

In the face of this, the rare academics who give time and attention to Pakistan have recently relied extensively on oral histories and also on media analysis to substantiate the description of the human toll of Partition – and, therefore, independence – beyond statistics (assuming these statistics even exist or can be traced).

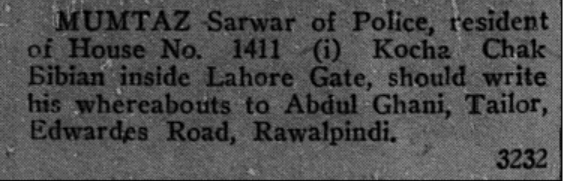

Newspapers, along with radio, in Urdu and English, were the main platforms available for displaced people (and those concerned with them) to make a case for themselves. There are classifieds advertizing business opportunities and details of lost loved ones, and passionate letters to the editor that signal discontent to state authorities.

Government organs and functionaries also relied on the tools of media to communicate with their new citizens, as they sought to shape that very citizenry.

There were photographs of politicians in ‘charismatic’ mode speaking and posing among refugees, who were often shown in either classic images of destitution and despair, or occasionally as heroic survivors, much like the new state of Pakistan, which claimed as part of its mystique a resilience in the face of many threats to its independence and security.

Of course, these resources were most available to those with certain privileges. In a region with relatively low literacy, and where rural areas were particularly affected by disruption and displacement, English and Urdu-language media were not truly representative of the struggles and joys of life of over five million refugees (and the deduction and absence of a similarly-sized population of non-Muslim evacuees).

The themes that emerge from the layout and content of a newspaper like Dawn, even when addressing the needs of the less privileged, can at best merely hint at the overall picture of what the newly-realized Pakistan meant for the lived experience of each of its constituents, especially those whose experience resisted easy packaging within bigger stories of the successful and best-possible emergence of the Pakistani state.

With this caveat, I have selected clippings from a newspaper with socialist-leaning bona fides called the Pakistan Times (edited by eminent cultural figure Faiz Ahmad Faiz) to show how news around the partition was expressed and shared by individuals, providing insight into the motivations and struggles that official histories have glossed over.

To contextualize these clippings, it is important to note that Pakistan was caught up in a frenzy of ‘pioneership’. Reporting on the Partition, into 1948, shared space with tales of battle and suffering in Kashmir and Palestine/Israel, lending an almost cosmological significance to local problems, which seemed to be reflected on the wider global stage.

It is also important to note that newspapers, as the original ‘social’ media, contained multiple voices, including dissenting ones. Hence, we have a remarkably regular series of messages by West Punjab’s civil supplies department, announcements about open meetings with police, as well as expressions of dissatisfaction with government actions, and direct communications between estranged friends and relatives (including non-Muslims).

Nabil loading microfilm into the computer at Widener Library

In selecting these clippings, I have chosen to highlight stories of unexpected relationships as well as glimpses into the lived experience of refugees and those individuals and organizations in relationship with these displaced.

The economy of displacement included, in small ways, the continuation of connections between Muslim and non-Muslim, as private transactions around property occurred before sufficient government management of property exchange between departing evacuees and incoming refugees.

The elite and upper middle classes were called out for aspects of their lifestyles during the ongoing emergency, and daily requests for aid to the national fund for refugee assistance (alongside reports of conspicuous donations made by schools, professional associations, townships etc.) emphasized generosity as a civic virtue of the new regime.

Newspapers facilitated communication in a period where other media were not as reliable. Refugees drew attention to the difficulties they faced in navigating their new lives. The government of Indore in India even used Pakistani newspapers to connect with potential incoming migrants.

This archive, like most, is a static one, so we do not know the antecedents or after-life of any of these pieces of newspaper art and literature (what, for example, was the Hindu or Sikh refugee’s response to the Indore announcement?); nonetheless, these excerpts allow us to focus our lines of inquiry as researchers on the texture of the social fabric of the newly formed dominions, with neatness and linearity in some cases, and deep complexity in others.

Nabil A Khan is a Visiting Scholar at the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, led by Professor Jennifer Leaning, at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. This is the first in a series of blog posts about SAI’s Partition Project.