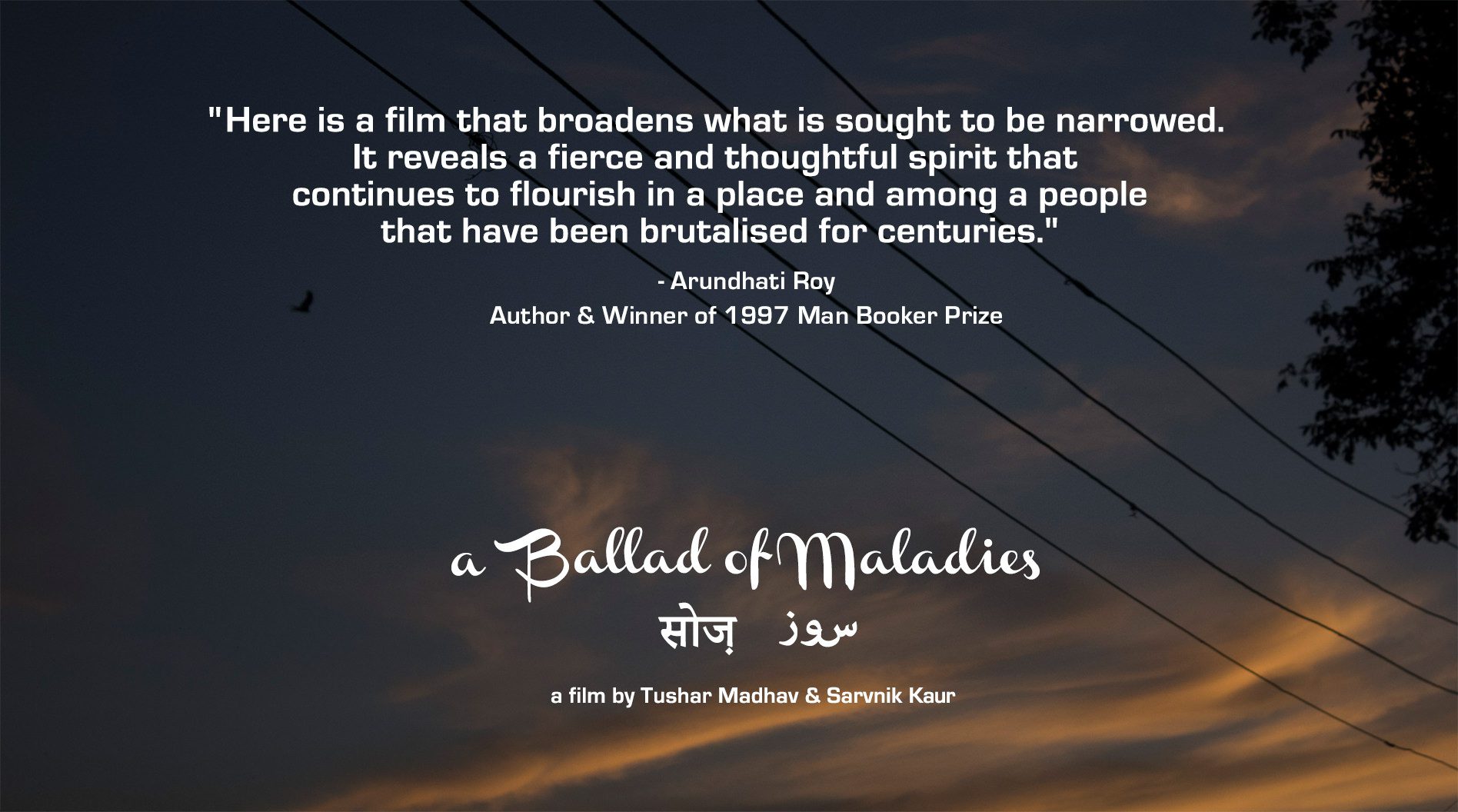

Tushar Madav and Sarvnik Kaur’s documentary Soz: A Ballad of Maladies gives the world a look at the Kashmir region without media-sponsored stereotypes or rhetoric.

Their film is a portrait of poets, musicians, and artists who have turned their art into weapons of resistance during periods of heightened state repression and violence in Indian-administered Kashmir.

In an interview with the Mittal Institute, the filmmakers of Soz: A Ballad of Maladies discuss their film and the importance of telling the overlooked stories of artistic dissent in Kashmir.

SAI will screen Soz: A Ballad of Maladies on Monday, April 9 at 12pm.

How did you decide to explore Kashmir through the music scene, as opposed to other communities?

Tushar:

Kashmir is one of the most troubled regions in South Asia today – its geographical location makes it a strategic geopolitical territory. The political belligerence of three nationalities consumes Kashmir, leaving no scope for a people’s own voice or history to surface.

Unfortunately, most mainstream discourses on Kashmir’s conflict are devoid of the region’s historical context. Kashmir has a history of political dissent through music and art that goes back more than 400 years. The contemporary Hip Hop artists draw heavily from their own folk traditions such as the Ladishah — a folk music art form that employs satire and poetry to critique ruling regimes. Art and music are born out of the lived experiences of artists and musicians, and we decided to use this alternate lens to understand Kashmir’s conflict.

Our journey into the region began in 2013, with a rock-music competition organized by the Army at a venue in Srinagar, which also functioned as a military garrison and interrogation center- guns and guitars featured on the same cinematic frame. As we dug more, Kashmir’s rich folk history surfaced as context to understand the region’s political conflict.

You have mentioned in past interviews that Kashmiris can be distrustful of the media. How did you find artists to participate in this project?

Tushar:

Mainstream Indian media is not particularly trusted in Kashmir, as it often misrepresents the voices of people to suit and conform to the state’s narrative on the region. Moreover, the popular media in Kashmir is heavily surveilled and controlled by the state and military machinery. Many young artists featured in the film, such as MC Kash, are underground since the Government of India has banned some of their work.

As documentary filmmakers, we had the privilege of not working against the deadline of an immediate news telecast. We knew that an agenda and narrative had to be found through our experiences with the artists, and that is exactly what happened.

Sarvnik:

The contemporary artists of Kashmir are aware of the landlocked predicament that Indian nation-state has imposed upon them. We, as makers of Soz, were aware of our own insignificance as members of a vast empire we call India. However, Soz held the promise to be a canvas that could bring to life the Kashmiri people’s struggle against the brutal occupation of their land, by way of personal experiences and narratives of its artists. We didn’t veer away from this intent, and as a result we were lent the expressions and voices by these artists to craft this film.

How did you navigate the challenge of gathering multiple narratives of such a complex conflict into one film?

Tushar:

The history of Kashmir is complex and rich. Someone once told us — “Nothing in Kashmir is straight except for the poplar trees”; and I believe it is very true. Since film is a very limiting medium, as it is bound by structures and timelines, we had to find a unifying theme to tie the film with a common thread. Art and music as a tool of resistance became that unifying thread and Zareef Ahmad Zareef’s interlocution helped us make sense of creating an overarching narrative for the multiple voices captured in the film. We spent a year editing over 100 hours of footage, and constantly restructuring it to find the best narrative.

How does Kashmir’s history of oral storytelling differ from the state-recorded history of the region?

Sarvnik:

Every year, people in power spend a lot of money keeping Kashmir at a certain level of rhetoric in the national media, which manufactures consent and adds fuel to the diatribes and virulent exchanges on social media. The young Kashmiris we met felt conflicted about the history that they studied at school and the ones that were sung at home.

The youth discover these oral and aural histories, and thus they view the present day from the prism of this experiential history that found no place in official narrations. The youth’s belief that their experiential history will be lost one day is strengthened by the administration and civil citizen’s denial of human rights violations, the unmarked graves and enforced disappearances. When Kashmiris are free to acknowledge their history without fear of persecution, I believe many separate narratives will find space to coexist peacefully.

Do you think art is an effective medium for protest?

Tushar:

Art and music transgress borders and languages. As a medium they also offer a palatable viewpoint to a conflict that seems to have become such a crucial block for India’s nationalistic imagination. MC Kash draws inspirations from artists like Tupac. Artists like Showkat Kathjoo speak through performance art to express their dissent.

I believe that guns and stones have a role to play in a fight against military occupation, especially for those who may not have the luxuries of producing art; however, art offers an alternate and perhaps a more sustainable path to digress from passion-driven calls for freedom and provide space for a much larger audience.

Sarvnik

During the making of Soz, I often wondered if art is an effective tool to wield when the oppressor comes armed with LMGs, AK47s and an entire system of oppressive laws to continue to persecute those who dare to protest.

As we spoke to MC Kash, a thought took root in my mind that I have not been able to shake off – that advocating that art is a better form of resistance might be a colonialist line of thought. People living through their bitter experience may or may not have the agency to express their dissent through art, but their lack of artistic ability should not deter them from expressing their political opinions. Theirs may not be an artistic expression, however, no one should write off their expression of dissent.

What do you hope people will learn from this documentary?

Tushar:

We hope that this film will allow people, both in India and abroad, to reflect upon the voices of the people who have experienced Kashmir’s long-standing history of violence and state repression. The film also offers a reason-driven understanding of the Kashmir conflict from the lens of music and art, which are as universal as air and water.

Sarvnik:

The film is an attempt to “re-story” Kashmir in the popular Indian imagination by illuminating this landlocked region’s historical milestones, in order to provide a context for present-day Kashmir. The idea is to move the discourse away from rigid binaries of national and anti-national; terrorist and patriot; Muslims, and Pandits – to arrive at an informed, empathetic, and certainly more humane perspective.