Murad Khan Mumtaz is a painter and a PhD candidate in Art and Architectural History at the University of Virginia. His primary research focuses on devotional portraiture with a special interest in representations of Muslim saints in early modern India.

Before his talk, we chatted with him about his Miniature Portrait training at the Lahore National College of Art, his influences, and journey into traditional musawwari painting.

How does your art practice inform how you approach your academic research?

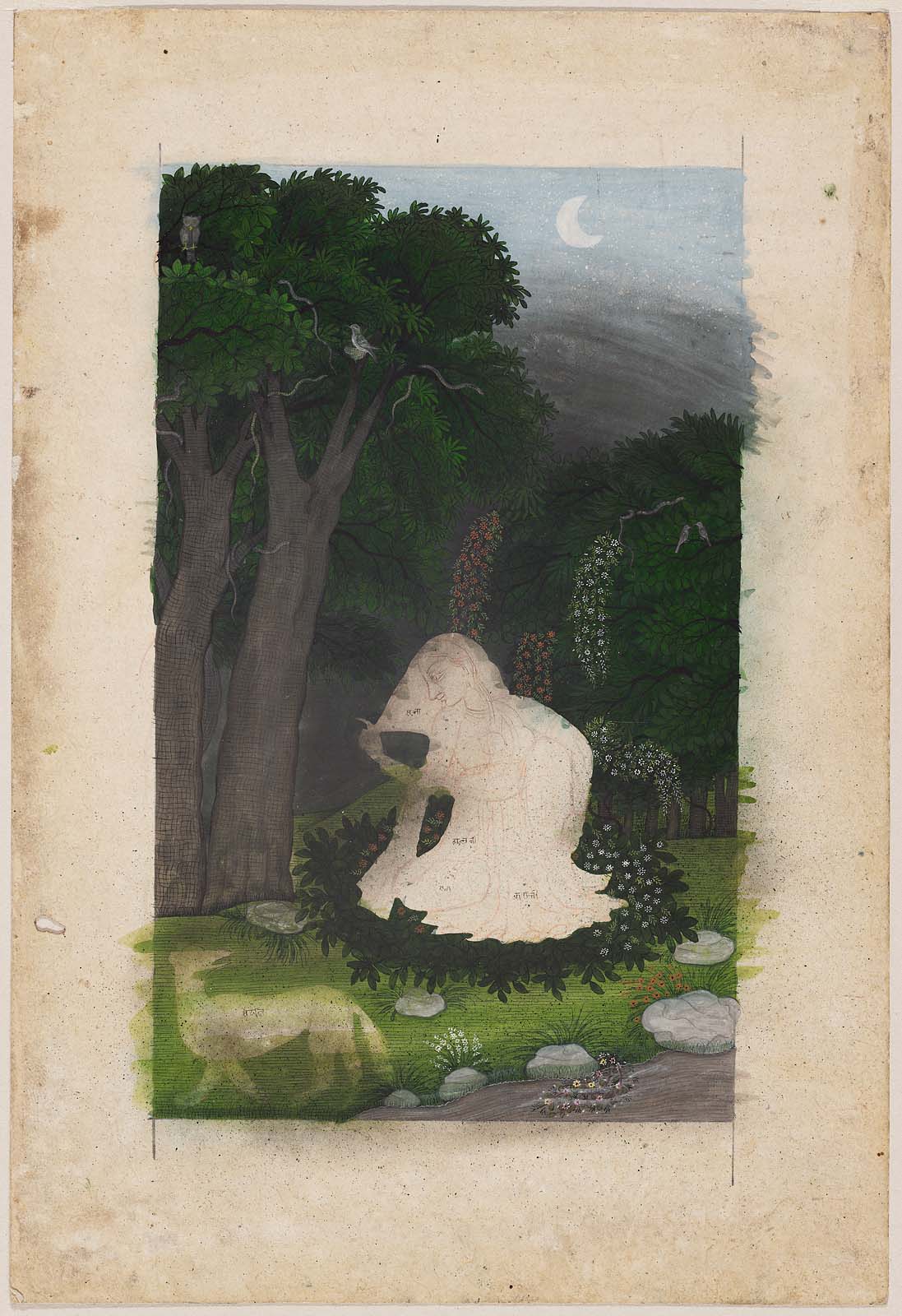

As someone trained in the practice of traditional Indian painting, I always look to investigate the processes involved in constructing a work of art. Looking at a seventeenth or eighteenth-century painting, for instance, it is fascinating to see how the paper was prepared, what pigments were used, and how the drawing was built up layer by layer (Fig. 1). Knowledge of the craft can also enhance a stylistic appreciation of an historical artwork, thus helping locate its school and period.

When did you first begin to practice musawwari painting?

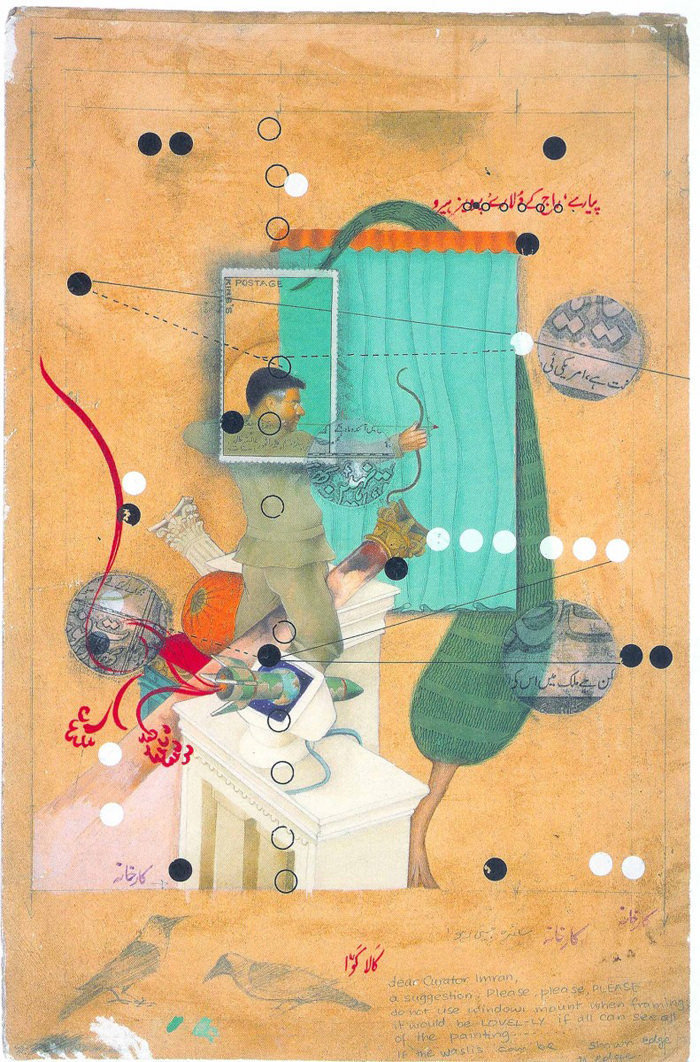

I started learning the technique in Lahore, at the National College of Arts in 2001. At that time, it was the only institution in the world that had a “Miniature Painting Department,” where you could complete your BFA in the traditional medium (Fig. 2). However, I began to realize that the school was teaching an attenuated technique that had been significantly altered during the colonial period.

The ethos of the College is deeply entrenched in modern and postmodern Western-centric canons of art making. As students in the Miniature Painting department, we were encouraged to produce art from within that worldview, rather than looking at our own cultural history, context, and intellectual framework (Fig. 3).

Subsequently, I learned techniques of Pahari painting (painting from the Punjab hills) from an artist who had learned from traditional musawwirs in India. That has given me a far deeper understanding of materials—such as natural pigments—and techniques (Fig. 4). This experience also helped me find links with the historical practice.

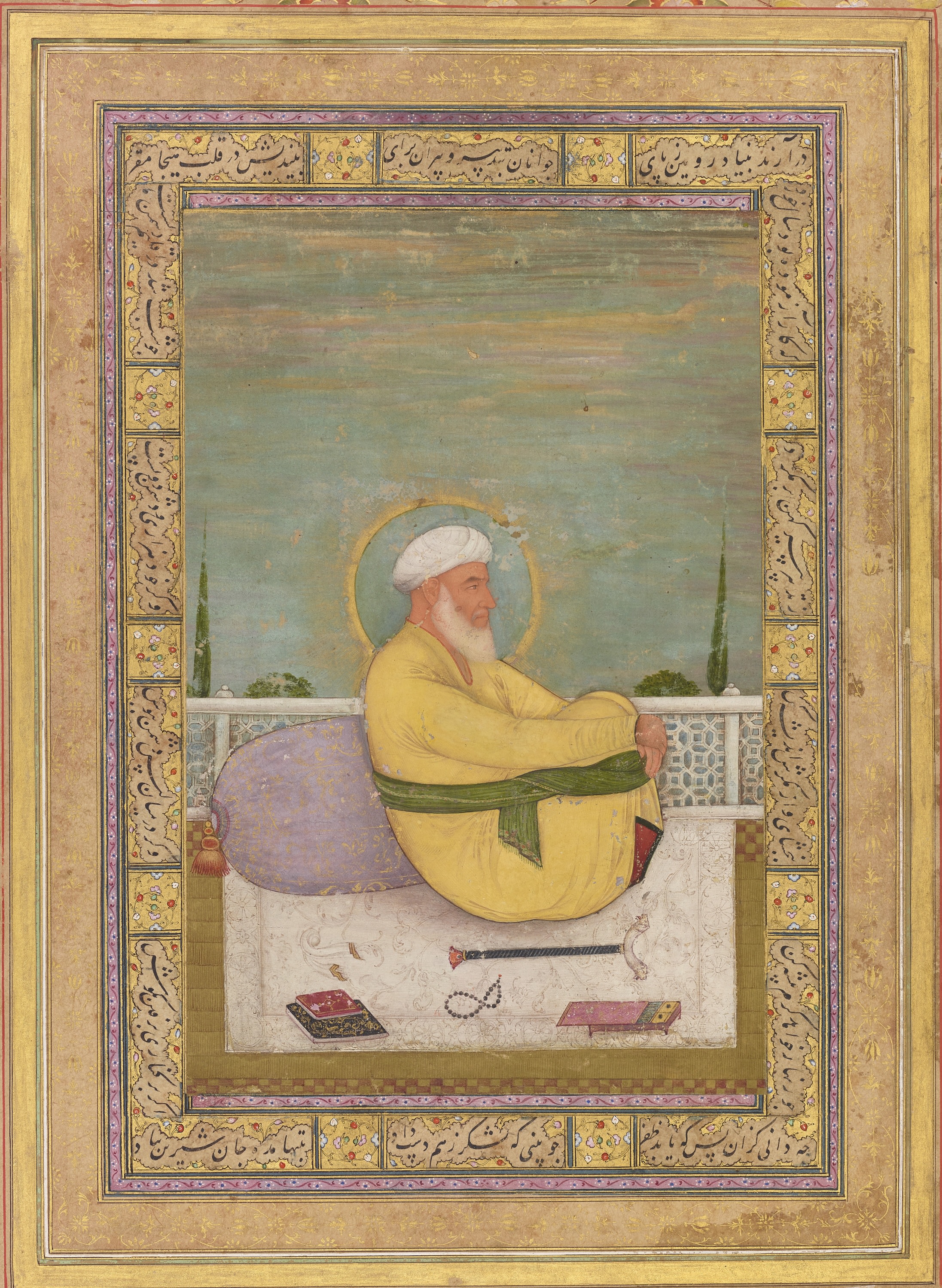

Most recently I have been greatly influenced by the masters of Pahari painting, particularly those working in the eighteenth century Basohli and Guler schools of painting (Fig. 7).

How has contemporary Miniature Painting practice in Pakistan diverged from the tradition of Indian painting?

For contemporary miniaturists in Pakistan, condensing a traditional methodology into a Western academic system has come with a heavy price; integral material and philosophical practices that were once transmitted organically through the ustad–shagird (the master–disciple) paradigm have been sacrificed. By contrast, musawwirs/chitrehras in India continue to be more rooted in the hereditary, artisanal guild system. However, in India patronage for the art form is rapidly dwindling. The mainstay is primarily the bazaar.

Could you describe your process of acquiring materials? To what lengths do you have to go to procure some of these rare pigments and other materials?

I get many of the basic pigments, such as vermillion, orpiment, and cinnabar from the old city in Lahore. Others, such as indigo and white can be bought from India. Interestingly, I collected many of the earth pigments, such as ochres, browns, and cadmium yellow while hiking in the mountains in New Mexico. These are the same pigments that are still used by santeros (icon painters) in New Mexico.

There are still families in Rajasthan that make traditional handmade wasli paper, and are the main source for paper. You can also get squirrel-tail-hair brushes from them. Although, one of the first things we were taught as students in Lahore was how to make your own brush using squirrel tail hair.

How do you address what you refer to as the paradoxical messages from the global art economy, which asks for “ethnic” aesthetics but judges by the established European canon?

In the contemporary art market—which is essentially the product of a Western and Westernizing discourse—there is no space for pluralistic art practices that want to engage with their own intellectual history. Recognizing this fact, I have gradually receded from mainstream art practice.

Contemporary miniaturist practice from Pakistan has been comfortably slotted into a niche that reflects larger trends in the art market. In general, for the last three decades or so, artists hailing from non-white—and especially Muslim countries—are given recognition only if they engage with issues of “identity politics” and cultural satire— particularly those who criticize, subvert, or characturerize their own cultural values.

Within this dominant system, Islamic calligraphy, for instance, or traditional musawwari made for a genuinely devotional function can never be considered as legitimate art forms. In a global context, these artistic expressions are primarily appreciated as historical objects behind glass cages in museums or in the auction house, but are seldom recognized as contemporary art.

Your talk and recent research explore the significance of the figure of a yogi as an emblem for the spiritual path of Sufism. What led you to explore this aspect of manuscript paintings?

When I started my research in collections around the world, I kept coming across individual folios from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that depicted portraits of local Indian saints: both Muslim and non-Muslim (Fig. 5). That led me to investigate the history of these images, as well as examining their function for early modern Muslim patrons. I realized that in the Indo-Islamic devotional landscape the figure of the yogi—both as a literary topos and as a visual metaphor—played a crucial role (Fig. 6). The image of the yogi still resonates deeply with Indian and Pakistani Muslim audiences as a figure of spiritual longing and detachment from the world.

How do you as an artist preserve tradition while allowing for innovation?

Tradition, which is derived from the Latin trādere, literally means to hand down, give or impart. Therefore, it is not something relegated to history. It is only meaningful as a term if it is living. And the best way to preserve a tradition is through practicing it. Once it is understood as a living system, and not as a static thing of the past to be viewed only in museums and catalogs, then the question of innovation does not even arise.