By Alvin Powell, staff writer, The Harvard Gazette

The birth of Hindu-led India and Muslim-ruled Pakistan in 1947 from what had been British India was horrifically violent, the start of a religious conflict in which millions died and millions more fled across the new borders toward safety.

The great sorting that occurred after the Partition of India remains the largest forced migration in human history, characterized not just by the bloodshed and tears with which it is often associated, but also by often-overlooked acts of courage and kindness, according to Harvard scholars studying it.

Partition’s echoes still resonate, and not just in the memories of remaining eyewitnesses. They are found in the two nuclear-armed nations’ postures toward each other, in the continuing dispute over their common border, in their modern demographics, in the reduced but still significant religious minorities in each nation, in the neighborhoods that arose where refugee camps once stood, and in the lessons learned that affect similar migrations such as that of Syrians currently fleeing civil war.

Since the fall of 2016, Harvard’s Lakshmi Mittal South Asia Institute has been taking a new look at Partition, which researchers say remains fertile ground for researchers despite prior work by scholars.

“What we’re trying to capture is this moment in time,” said Jennifer Leaning, the FXB Professor of the Practice of Health and Human Rights at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “It is an extremely important part of world history.”

Researchers now can deploy tools enabled by advances in technology, computing, and data science, that let them ask fresh questions and take different approaches to answering old ones. In addition, research that relies on memories of eyewitnesses to the 70-year-old episode gains urgency with each passing year.

“Obviously, it’s urgent because those who lived through this trauma inevitably won’t be with us much longer,” said South Asia Institute Director Tarun Khanna, whose family resettled from Pakistan to northern India at the time. “Partition is a super-extensively studied issue, but also it’s my perception that there are many angles that are utterly unstudied.”

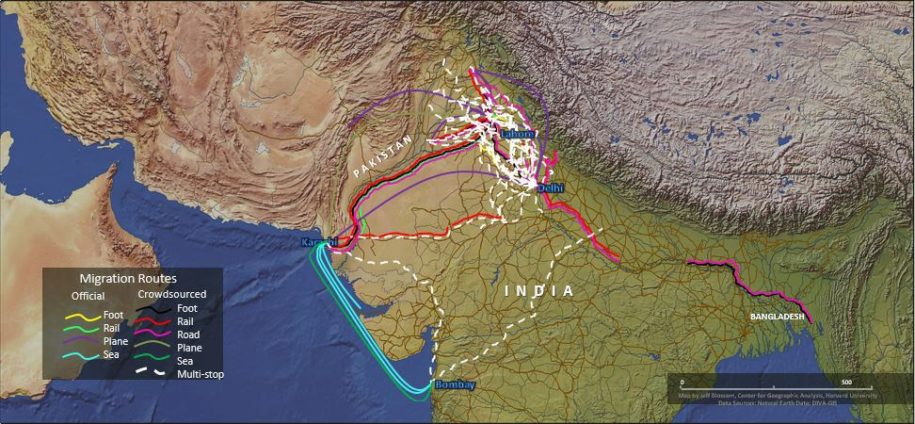

Millions took to the land, sea, and air to escape religious persecution in the Partition of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

The project is designed to appeal to scholars from across Harvard in a way similar to that of the institute’s 2013 project on the Khumb Mela, a massive, eight-week religious festival that occurs every 12 years and brings millions of people daily to the banks of the Ganges River. Scholars participating in the Khumb Mela project examined the event from viewpoints involving religion, public health, urban planning, government administration, security, and commerce. Steering the current project are Leaning and Khanna, who is also Harvard Business School’s Jorge Paulo Lemann Professor.

“Our power is to bring to this project, this topic, to people who would not normally look at it,” Khanna said.

“Looking Back, Informing the Future: The 1947 Partition of British India” is supporting four avenues of inquiry. One, led by Leaning, is examining the humanitarian implications of migration, focusing on relief efforts and resettlement of refugees by different levels of government, as well as non-governmental organizations.

A second, led by Khanna and Karim Lakhani, Charles Edward Wilson Professor of Business Administration, is seeking to collect and analyze the oral histories of 3,000 survivors, with an emphasis on those not represented in earlier histories: women, minorities, and the poor. The third project, led by Rahul Mehrotra, professor of urban design and planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, is examining Partition’s impact on cities, including some of the subcontinent’s largest urban areas, like Bombay, Calcutta, Dehli, Lahore, and Karachi.

The fourth (but not final aspect, since Khanna anticipates more in the future), examines the geopolitics emerging from Partition, focusing on analysis of political speeches by leaders of India and Pakistan delivered on the international stage. That is led by Asim Khwaja, the Harvard Kennedy School’s Sumitomo-FASID Professor of International Finance and Development, along with Khanna, Lakhani, and Prashant Bharadwaj, an economics professor at the University of California, San Diego.

That project will benefit from the tools of modern information technology and data science, which allow not just the large-scale, big-data analyses of traditional information, but also increasingly allow analysis of unconventional data sets, like the content of political speeches where common themes emerge from word choices and language analysis.

The work, aided by institute staff including project manager Shubhangi Bhadada and research assistants Saba Dave, Nabil Khan, Rasim Alam, and Ajay Kumar, is being done in collaboration with partners in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, which at the time of Partition was part of Pakistan. Those local partners include scholars, project staff, and an army of research assistants who act as “ambassadors” to conduct structured interviews with Partition survivors.

In addition to the research, the institute last spring sponsored weekly seminars on Partition-related subjects on campus and has held meetings on the project in Cambridge, Providence, London, New York, Karachi and Lahore, Pakistan, and Delhi, India.

Though the Partition project began early last year, one of its investigations, Leaning’s exploration of Partition’s humanitarian aspects, had a head start. More than a decade ago Leaning started exploring refugees’ experience during migration, how they were handled on arrival, and what sparked the religious and ethnic violence.

Partition team members Rahul Mehrotra (clockwise from center) Diane Athaide, Saba Dave, Shubhangi Bhadada, Nabil Khan, and Rasim Alam pore over Partition interviews and documents. Photo courtesy of Shubhangi Bhadada.

“Some people moved hundreds of miles to the border, and the violence precipitated their decision to leave,” Leaning said. “[The violence] became quite intimate in these rural villages.”

In research published in 2008, Leaning and colleagues, including Kenneth Hill of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, argued that Partition affected many more people than previously thought.

Instead of the 14.5 million thought to have moved from country to country in previous estimates, Leaning and colleagues said up to 18 million may have moved, and between 2.3 and 3.2 million likely died in the violence. Research published in 2008 by Bharadwaj, Khwaja, and Atif Mian reached similar conclusions, saying there were 17.8 million migrants and 3.4 million killed.

At the time of Partition, the setting was ripe for a breakdown of order, Leaning said. Nascent Indian and Pakistani governments were still getting their feet under them, while the former colonial power, Britain, was broke and exhausted after World War II. Britain was demobilizing troops who might have proven useful in responding to such a large-scale humanitarian disaster and preparing for an exit from the region, Leaning said. Despite unrest for months before Partition, British officials were “surprisingly unprepared,” Leaning said, and preparations made at the local and provincial level were swamped by the numbers of people moving.

“The problem was the numbers were overwhelming,” Leaning said.

Making things worse, she said, was that among those demobilized were former soldiers who had served in the British Indian Army, arriving home with not only military training, but also with their weapons.

Leaning said that might explain something that always puzzled her about Partition: the relatively high death rate. Many more were killed then might have been expected in a similar setting. But if demobilized troops took part in organized attacks on refugees, those attacks would have been particularly deadly.

“An enormous number were demobilized but not disarmed,” Leaning said. “This was not just mass hysteria violence. There was a high level of organization and lethality.”

Results from the Partition project’s more recent investigations will likely come out later this year, and a book presenting the results is planned for next year. Khanna said he expects inquiries on the subject to continue beyond that, possibly for several years.

“We started this on the 70th anniversary,” Khanna said, “I’m hoping by the 75th anniversary of Partition we would really have published quite a few things and been able to showcase what we learned from a long-running project.”

This article was originally published by The Harvard Gazette on April 6, 2018.