By: Bronwen Gulkis, PH.D. Candidate, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Harvard University; The Mittal Institute Winter Grant Recipient

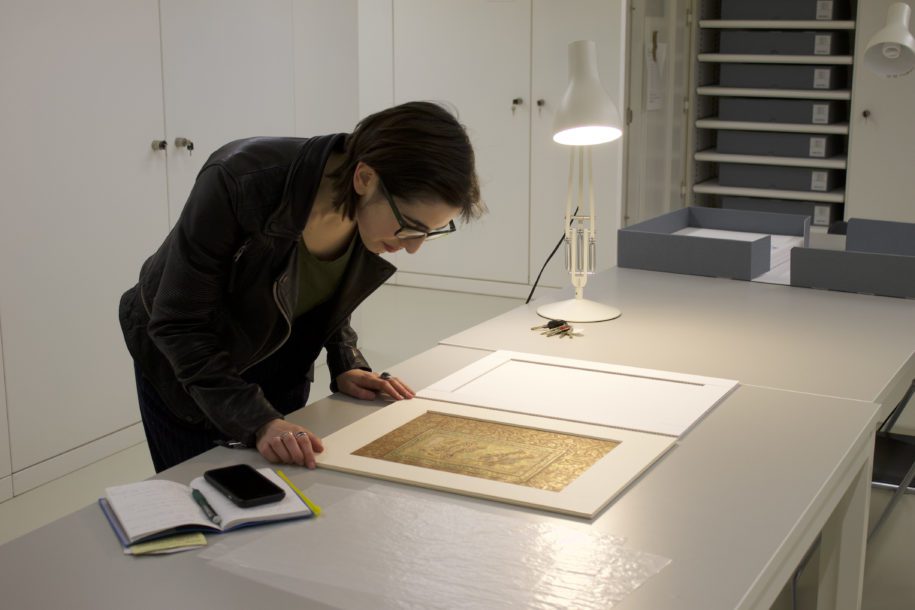

Was that a flash of gold I just saw? I moved around to the other side of the table, hoping to catch the light just right again. I was in a storage room of the Archäologisches Zentrum of the Museum fur Islamische Kunst in Berlin, viewing a folio of calligraphy signed by the Mughal prince Dara Shikoh (1615-59). I tilted my head as I followed the flowing lines of nast’aliq script around the page. The calligraphy was richly illuminated, surrounded by a pattern of colorful floral tracery on a gold ground. But underneath the strokes of black ink, a hint of gold in the marbled paper had caught my eye. With the assistance of a helpful museum director, I lowered a lamp along the side of the page, focusing a beam of raking light — the preferred method for illuminating texture and detail — across the surface of the paper. Suddenly, the dull tones of the marbled paper glittered with a delicate pattern of gold pen-drawing.

I was traveling between London and Berlin on my winter break, completing research for a dissertation chapter on Mughal princes as patrons and collectors of illuminated albums. Over the course of the seventeenth century, the album format (known as a muraqqa’ in Persian, the language of the Mughal court), became the dominant method for storing and displaying works on paper in Mughal India. Roughly analogous to a contemporary museum exhibit, an album might combine paintings, calligraphy, and textual selections to suggest an artistic theme or a historical narrative. In doing so, albums also reveal the larger story of art making and consumption in Mughal India.

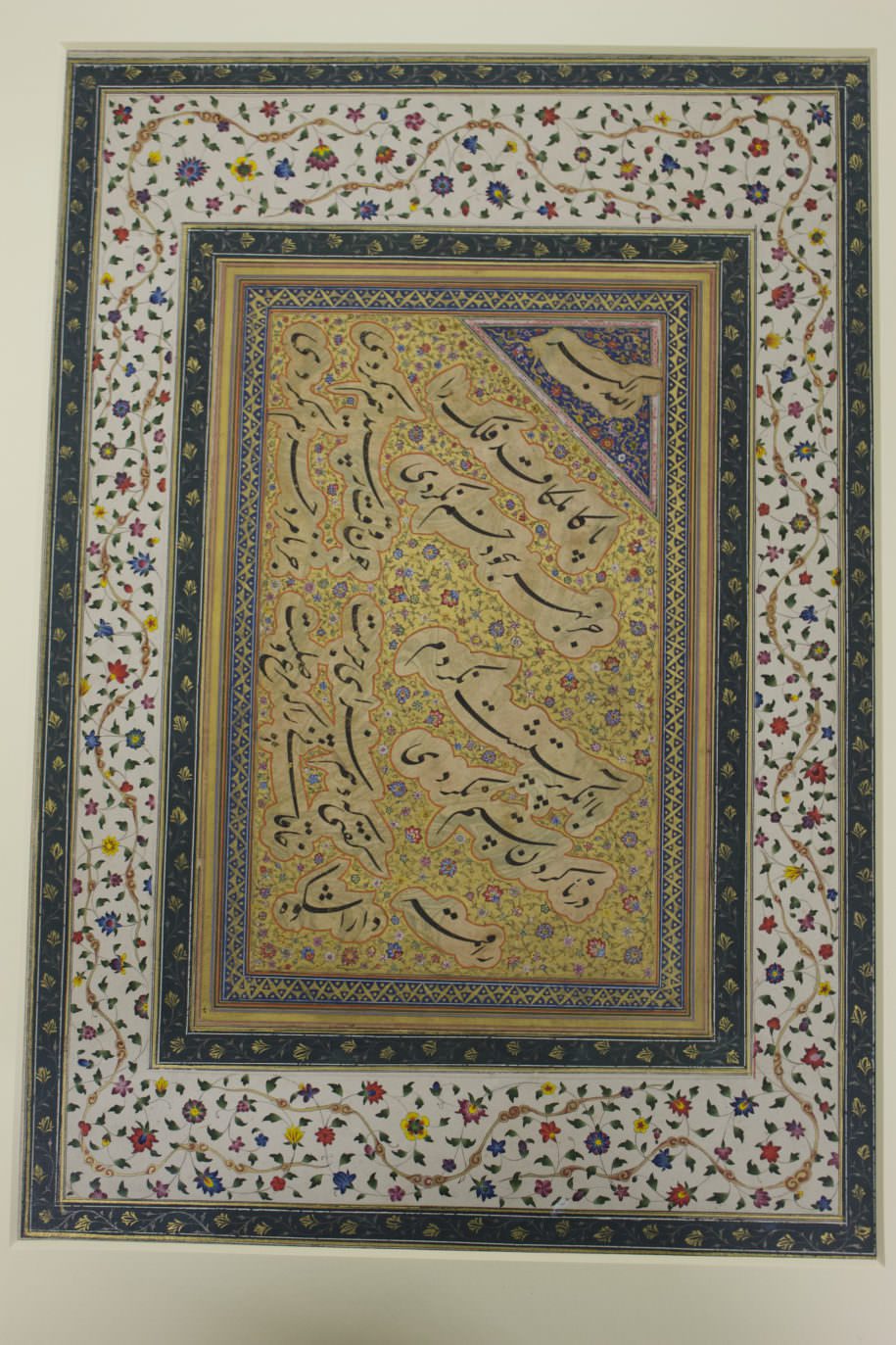

Mughal albums often preserved lines of script by famous calligraphers, whose work was considered superior to painting in much of the Islamic world. However, some album folios from the Shahjahani era contain calligraphy by members of the Mughal royal family themselves. Works by Dara Shikoh, the favorite of emperor Shahjahan’s four sons, were often mounted on albums folios after being heightened with gold and painted ornament. Conversely, Dara Shikoh’s name was removed from most of these after he was captured and executed by his brother Aurangzeb, who overthrew Shahjahan to reign as emperor from 1658-1707.

In 2017, I received a winter travel grant from the Lakshmi Mittal South Asia Institute to travel to Europe and conduct research in the main repositories where these calligraphies are now stored: the British Library, the British Museum, and the Museum fur Islamische Kunst, Berlin. As a complement to my dissertation chapter on Mughal princes as album patrons, I viewed calligraphies from Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb to gather data on how these works were made, viewed and used.

Over the course of their rule, the Mughal brothers collected a variety of illuminated manuscripts. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Though all three institutions have digitized many of their most famous works, online images can only tell part of the story. In my travels, I was able to view acquisition documents, ownership records, and other documentation that is only made available to researchers. As an art historian, I also observed how the materials and physical characteristics of these objects conveyed information about their use and circulation. Album folios are small by the standards of Western painting, often under 18” high, but can be packed with details. They are often pieced together from multiple sheets of paper — the word muraqqa’ refers to a patchwork —and display a variety of painted and decorated surfaces including paintings, calligraphy, gilding, or marbled or dyed paper. These material details are often lost in photographic reproductions, which present the whole folio as a flat, even surface.

Observing these details was a constant source of pleasure and surprise during my fieldwork. At the Museum fur Islamische Kunst, two folios still show traces of the Dara Shikoh’s signature. A third one has a full signature, which I had theorized was a fake. But on seeing the gold pattern on the marbled paper, I realized it shared these many characteristics with the contemporary specimens of his calligraphy. The contours of the calligraphy, the tones of the marbling, and the gold drawings were all features I had seen on signed and dated calligraphies. The quality of the materials and level of workmanship suggested that the calligraphy was ornamented in an imperial workshop at some point in its history — a far cry from the dull beige paper I had seen in color reproductions. Thanks to my time in museum storage with these objects, I was able to incorporate fresh ideas about authorship and authenticity into my chapter.

The calligraphy and gold leafing can help give insight into the manu's creator. Image courtesy of Bronwen Gulkis.

The delicate gold background that I observed in the Berlin folio was just one example of what can be accomplished through this sort of research. A partial folio of Dara Shikoh’s calligraphy from the British Museum (1921) is surrounded by gold and ornamented with five species of paired birds and red, purple, and yellow flowers. I spent an afternoon at the British Museum documenting the minute painted birds and flowers that surround the calligraphic verses by the Sufi saint Miran Muhiddin. A horizontal smear in the lower register of the composition shows where Dara Shikoh’s signature was erased, presumably after his defeat and execution. While it is tempting to see these alterations as flaws, they often provide the most clues to how these works were made and used.

As I pored over the folio with my magnifying glass and zoom lens, I began to notice discrepancies that could not be explained by the narrative of “sibling rivalry” between Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb. A thin gold line around the inner border of the calligraphy did not line up with the outer, pink-and-gold decorated border. The calligraphy in the upper right corner was just barely cut off, and though the cloudlike tahrir (outline) continued onto the outer border, the sharp white line did not align with the swooping contours used to outline the rest of the verses.

These points suggested that the entire sheet had been set in a different mounting at some point after its creation. If Aurangzeb wished to destroy the memory of his brother, why had this work been preserved in this way? Why, for example, was the signature covered in such an obvious manner? The passage at the bottom — where the artist is commonly identified — could have easily been removed entirely, instead of painted over. Maybe it was important to preserve the memory of Dara Shikoh’s defeat, or perhaps the calligraphy entered the collection of a sympathetic nobleman or librarian, who was not willing to erase the prince’s contribution in its entirety. These questions of personal motivations hang on memory, authorship, and identity run through my study, and I hope to present a comprehensive answer to them in my completed dissertation.