Faiham Ebna Sharif recently gave a presentation titled “Cha Chakra: Tea Tales of Bangladesh,” chaired by Professor Sugata Bose with commentary by Curator Alison Nordström, in which he displayed his long-term documentary photography research project on tea industry. The project sheds light on the plight of the tea garden workers of Bangladesh who are among the lowest paid and most vulnerable laborers in the world, yet are strangely invisible to the global media. Currently, the project concentrates on labor rights and conditions within Bangladesh’s tea industry, which are a direct result of a long history of colonialism and oppression. This project aims to collect the undocumented history of the global tea industry through photography, oral histories, and archival materials.

His other ongoing projects include Rohingya: The Stateless People, The Fantasy Is More Filmic than Fictional: Bangladesh Film Industry and Life in Progress: People Living with HIV.

Before his return to Bangladesh, we talked with him about his art practice and time here at Harvard.

What experiences motivated you to work on themes surrounding social justice?

I work with various art mediums to explore what is happening around the world. When I was a University student, I was looking for avenues to express my thoughts about what was happening around me. During that time, I worked on films, documentaries and was involved in different cultural movements. I realized that photography was the best medium to express both my individual views as well as speak about the experiences of larger groups of people.

I started working on social justice issues as a journalist. For instance, I first went to the Tea Gardens on an assignment to cover the tea workers’ movement. I soon realized that the plight of the tea workers is a deeply rooted issue that the media cannot adequately cover in a few journalistic reports, so I decided to work on the project long-term.

What has been your approach to photographing your subjects?

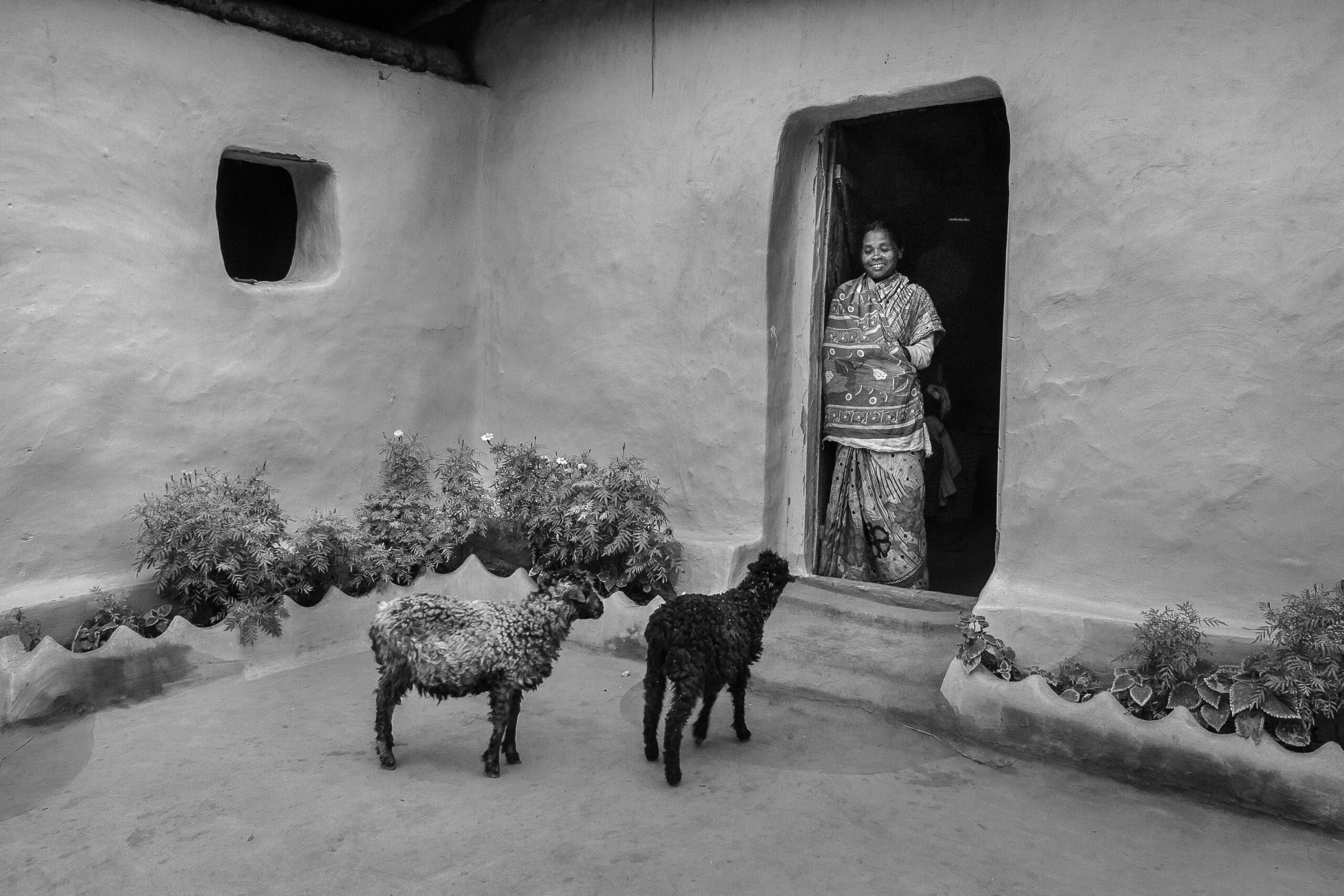

The logical approach is to spend time with the people I photograph. For example, I stayed in the Tea Gardens with the workers for many days. I talked to them and got to know their stories. I believe that collecting testimonies and oral histories are an important part of the work. One challenge is that people will always see me as “other” because I see them from outside, and vice versa.

What are some of the strategies that you use to connect to your subjects?

As a student, I studied research methods. However, over time I have developed an intuitive approach. For example, I drink tea with the tea workers to spend time with them and get to know them. My intention is not to intervene in their lives, but rather to talk to them and invite them to ask me what I want and why I am there. It is important for me to become friends with the people I work with because otherwise, it is tough to get stories from people. As a storyteller, I believe everybody has a story to tell, however, collecting the stories is not always easy. People have to trust me and that requires time to build the relationship.

What is the rationale behind having multiple ongoing projects?

For me, as a documentary photographer, it is important to work on subjects for a longer period. I see most of my works as long-term projects. It is tough to wrap up a story within a short span of time.

What has been your experience at Harvard?

It has been an incredible opportunity to be able to access Harvard’s library and museum resources as a researcher and to dig deeper into my studies. It is difficult for me to access comparable archives and libraries as a freelancer. Additionally, Cambridge is a cosmopolitan area where I have met people from different areas of the world. It has been fascinating and helpful for my journey as an artist.

How did your seminar go?

The seminar brought together people from different professions as well as students, faculty, and representatives from the Bangladeshi community. Even the person I am subletting from came! It was inspiring to present my work in front of such a diverse audience. The audience was asking incisive questions, so it was a very good learning experience for me. It was a collective effort to organize the seminar, and I am grateful to Professor Sugata Bose, Curator Alison Nordstrom, Aniket De (Ph.D. student in history) and the Mittal Institute staff.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

-Amy Johnson