Mahbub Jokhio, one of the Mittal Institute’s newest Visiting Artist Fellows for Spring 2019.

Mahbub Jokhio is one of the Mittal Institute’s newest Visiting Artist Fellows, bringing with him a wealth of talent that he uses to create issue-oriented art and inquiries into this life and experiences in Pakistan. His interest in and pursuit of art was shaped by artists before him, whom he has come into contact with throughout his life.

“I was born into a very literary family full of artists, poets, and writers. The art was in the blood. My uncle, an internationally recognized visual artist, basically channeled my interest into visual arts. Since then, I have been involved in the visual arts,” Mahbub said. “I went to Lahore in 2010 for my Masters at Beaconhouse National University, where I had the opportunity to meet Rashid Rana, the father of contemporary art in Pakistan. He really shaped my understanding of art. I think most of my generation, and generations before me, have been influenced by his practice over time.”

Mahbub’s mediums range from photography to video to massive concrete structures — and everything in between. All works have a meaning, a true symbolism behind them, while inviting viewers to come up with their own interpretations. Recently, we sat down with Mahbub to learn more about the meaning behind his art and his hopes for the future.

You’ve spoken about your artwork being a departure from popular Western art and influences. How do you think this makes your work stand out?

I’ve always believed that an artist is like a radio. So, if you put that radio in Pakistan, it would transmit what’s in the air at certain times and certain places. But at the same time, if you put that radio in the USA or somewhere else, it will only transmit what’s in the air in that given context.

My practice keeps on changing with time. I have a variety of subject matters, and I get very excited with new ideas. I want to push myself as an artist with newer subjects, newer media. But my earlier practice has been very referential, which also sometimes happens now. If you see my Graveyard project [the As Time Passes in the City of the Buried series], it’s actually about something completely different, but when you see it from the Partition perspective, it creates a new narrative, and you could actually see it as a reflection of Partition.

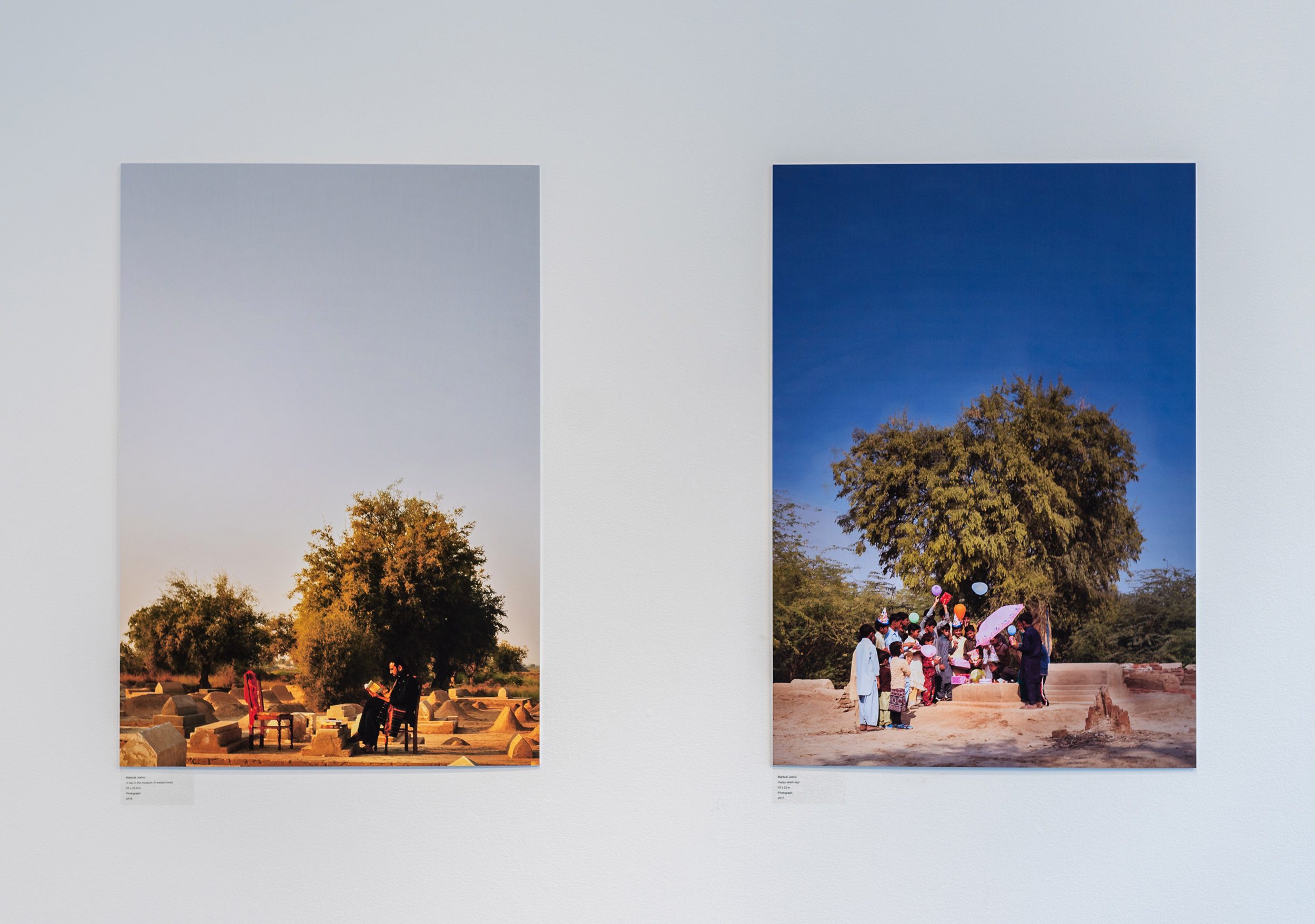

One piece within the series “As Time Passes in the City of the Buried,” by Mahbub Jokhio.

At the same time, that work is also about photography as a medium. They say photography is the death of reality. I see a photograph, and it becomes a celebration of the death of reality. The whole project revolved around death and life, and how they both exist in the same location. You can photograph something that binds these two realities: the constructed reality and the absolute reality — the whole idea of illusion. My practice keeps on changing with time, and my ideas and my subject matters as well. It has a huge range of concerns.

Two pieces within the series “As Time Passes in the City of the Buried,” by Mahbub Jokhio, currently on display at the Crossings Gallery of the Harvard Ed Portal in Allston.

I didn’t originally see the Graveyard project in relation to the Partition. The whole idea was, in Pakistan especially, graveyards are not frequently visited places. They’re very scary and abandoned places; nobody would go there. So that project was a suggestion that the graveyards could be a place where life could happen — you should go see it and pay homage to your loved ones. So, the project was about a public place that should have activity and frequent visits. When I saw it from the Partition perspective, it completely shocked me. It actually made much more sense, that project. And I think that’s the beauty of art: there tends to be so many interpretations that the creator wouldn’t have thought of.

One piece within the series “As Time Passes in the City of the Buried,” by Mahbub Jokhio.

What kind of impressions or legacies has the Partition had on you and your generation in Pakistan?

I don’t have any relation to Partition — like a direct relationship. But I have this huge influence, you can say, of the Partition as a human being more-so than a victim of that event. As a human being, it really makes me sad to know about the Partition, it dislocated so many people and it was a complete disaster. It was not designed very well and it only led to chaos, and that chaos can still be seen in that region. The older generation who actually witnessed that event, I think it lives with them, and it somehow transferred to a generation like us.

A group of people enjoying Mahbub’s work on display at the Crossings Gallery of the Harvard Ed Portal in Allston.

I was looking at a piece you’ve done, called They are Deaf, Dumb, and Blind. What does this work represent to you?

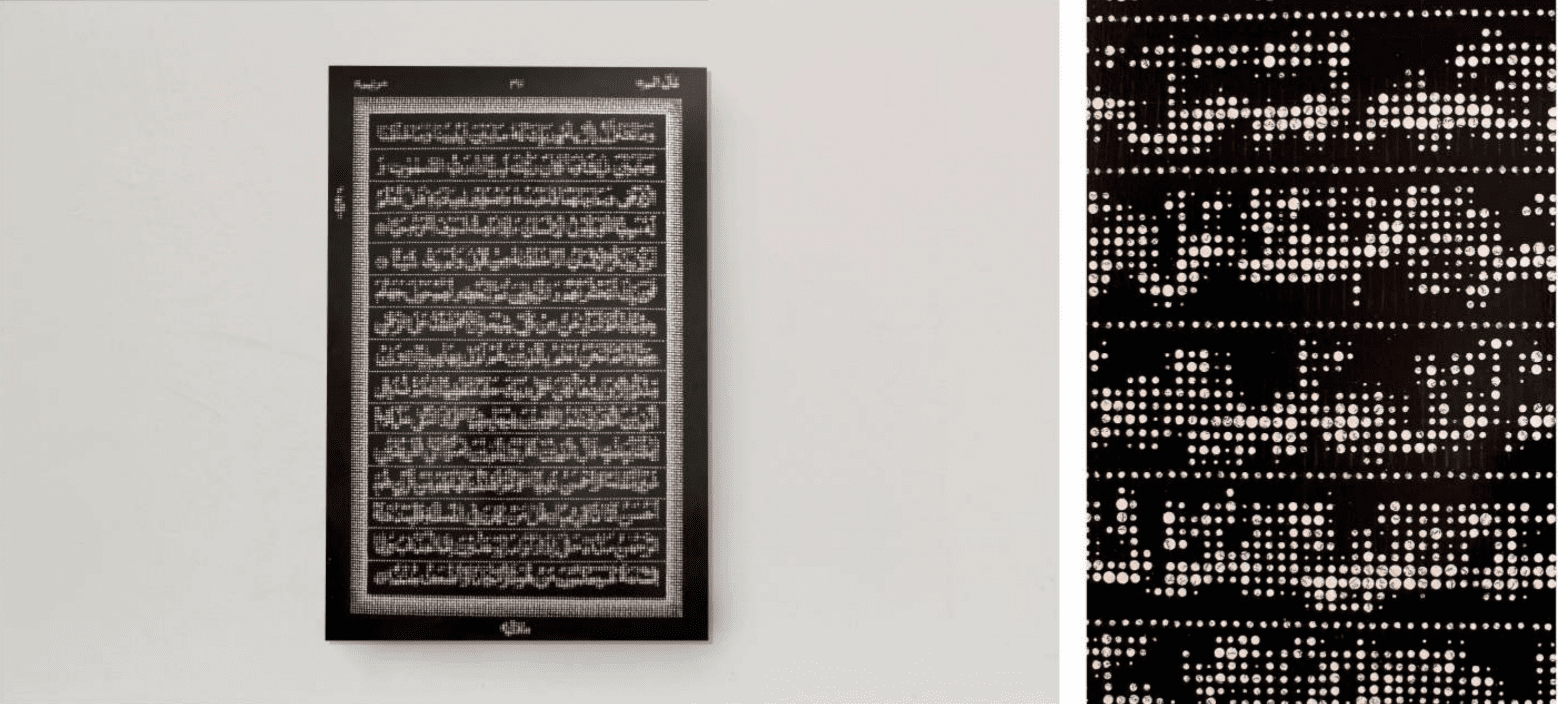

It’s an image of a Quran page, the holy book of Islam, but it’s actually made out of small circular cut-outs from a Sindhi poetry book called Shah Jo Risalo by Shah Latif. So, when you see the work from afar, it creates an image of a Quran page. But when you come closer, the image breaks into abstraction. The image is no longer there, so you’ll see an unreadable text. And the Sindhi text in the poetry cutouts, you can’t actually decipher that as well. So, the text works purely as an image.

A piece called “They Are Deaf, Dumb, and Blind,” from a series entitled “Words Are Image Makers Too,” by Mahbub Jokhio. Full piece on the left, and detailed close-up on the right.

That’s also the case in most of the Muslim countries; you could say [a large portion of] the population can’t read the Arabic text, but they can tell you that it’s an Arabic holy text. For them, it only works as an image. And the remaining population can actually can read it, but they can’t make meaning out of it. So, the whole work is about how the Arabic text is working as image. Islam is a very recent thing that happened to us, about 1,400 years back, so the work also comments on this adaptation of newer religion, which brought with it its own culture and collapsed with the ancient culture of Sindh Pakistan. It shows, in a way, how we couldn’t make sense of both cultures — the Islamic one and the local origin. So [in the work], both are in abstraction.

Do you try to create artwork that comments on your world and society, and how they impact you?

Definitely. I think art should not be limited by walls, and it should have a meaning, an inquiry, a new thought for the viewer. I always believed that art should be issue-centered. I work with these public places, and how we make meaning of things. There are so many themes and current issues that keep on reflecting in my work in Pakistan.

What do you hope to accomplish in this fellowship while you’re here?

I have always believed that the city and the people you meet tend to leave their impression on you for a long period of time. It adds to your experience as a person, and, for me, as a maker. Apart from that, I’m very much looking forward to learning more about the ongoing project of the Mittal Institute, which deals with oral stories from the Partition. I want to create a project that shows a visual history of the event.