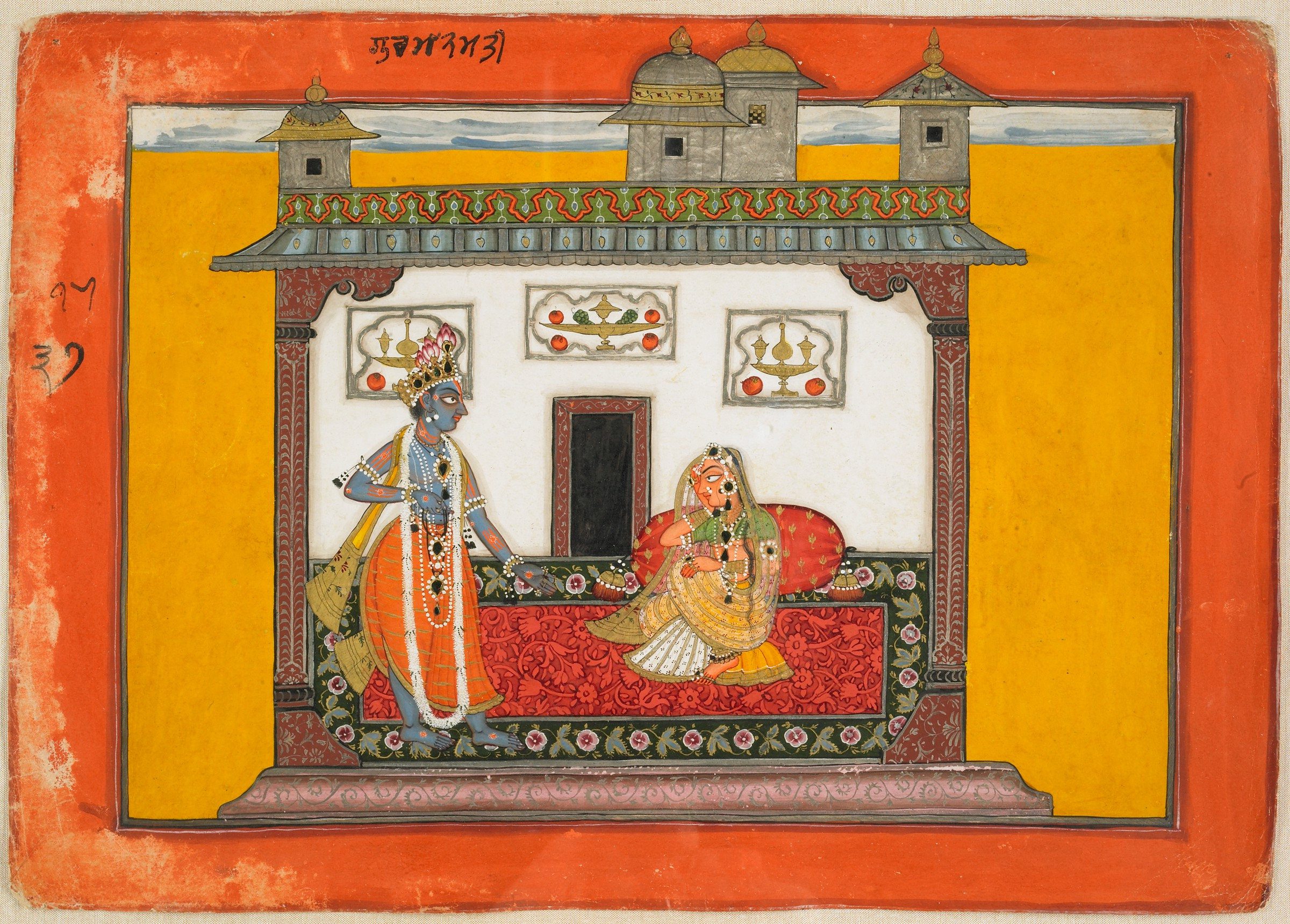

Unknown artist, A Nayika and Her Lover: Painting from a Rasamanjari Series (A Bouquet of Delights), Indian, c. 1660–70. Opaque watercolor, gold, and beetle-wing cases on paper. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of John Kenneth Galbraith, 1972.74. Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museums.

Each year, Asia Week New York gathers the world’s best auction houses, museums, and Asian art specialists for a weeklong event celebrating the importance of Asian art and drawing a crowd of collectors and curators from all over the globe.

This year, Professor Jinah Kim — George P. Bickford Professor of Indian and South Asian Art at Harvard University — and Dr. Katherine Eremin — Patricia Cornwell Senior Conservation Scientist at the Harvard Art Museums — teamed up with Christie’s as part of the Mittal Institute’s Arts Program to give a talk at the event, exploring their work with color and pigments used in Indian paintings and the science behind conservation and restoration.

How Blue Is Krishna?

Professor Kim started off the talk with a simple question: “How blue is Krishna?” Displaying a wide range of depictions of Krishna in Indian paintings dating between the 1400s and 1800s CE, Professor Kim noted how the shade of blue varied in each image — even in some that belonged to the same manuscript.

Krishna with gopis, from the dispersed Bhagavata purana series, possibly Mathura, c. 1520-1530, Harvard Art Museums, acc. 1974.124. Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museums.

“Although we see blue in the sky and water, or in brilliant wings of butterflies, most blues that we see in nature are structural colors and not chemical colors. This means that their color is the result of light refracting in a special way, rather than their molecules reflecting blue light. It’s a play of light. The pigment ultramarine, made from the Lapis lazuli, is one of the very few naturally occurring blue pigments,” Professor Kim said.

That ultramarine pigment was often used to create the brilliant-blue hue used in Indian paintings of Krishna. “Krishna’s blue color has a complex history, and artists’ interventions played a major role in shaping what color Krishna was to be seen in any given period,” said Professor Kim.

And while the artist had their own methods and interpretations of the color, they were also constrained by the availability of materials during their time period. “I suggest that the availability of certain materials and technical advancement in pigment preparation and application … contributed to different ways in which Krishna’s color was pictorialized,” Professor Kim said. “Natural ores of Lapis lazuli are extremely limited — mostly concentrated in Afghanistan — and the term ultramarine, suggesting ‘across the sea,’ beckons the far distance from which the pigment was sourced, making it a costly commodity in ancient trade.”

Professor Jinah Kim (left) and Dr. Katherine Eremin (right) discuss their work at Asia Week New York.

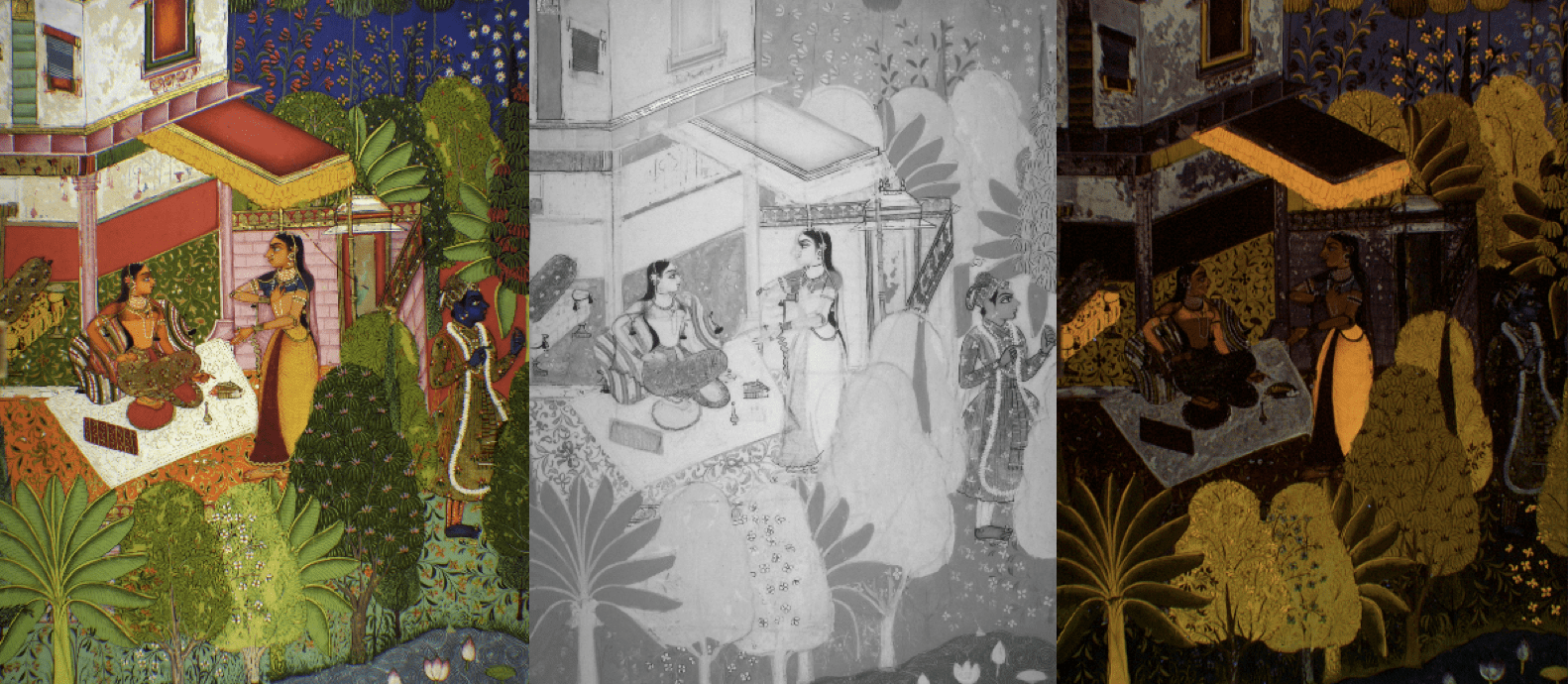

Beneath the Layers

So, how do scientists, conservators, and scholars learn more about the colors and the chemical makeup of pigments used in these ancient paintings? Dr. Eremin discussed the work of scientists and conservators at the Harvard Art Museums and her team’s efforts to analyze Indian manuscripts and paintings using scientific techniques, including Raman spectroscopy, x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, and more. This project, collaborating with scientists and conservators — including Penley Knipe, Head of Paper Lab, and Dr. Georgina Rayner, organic specialist and Associate Conservation Scientist at the Straus Center — uses the Straus Center’s Video Spectral Comparator 8000 to take images and analyze this historical artwork.

The first image shows the painting viewed in visible light, the middle image using infrared spectroscopy, and the third using UV light. Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museums.

Through these efforts, the team seeks to unlock the secrets of these paintings buried in their layers and chemical makeup. Dr. Eremin discussed how her team has worked “to determine the materials and techniques used and how these vary with manufacturing location and/or date, allowing researchers to understand the geographical and chronological ranges in the use of different pigments over the Indian sub-continent.”

Using non-invasive spectroscopy techniques, the team at the Harvard Art Museums learn more about the pigments the artists used in their paintings, while uncovering vast amounts of additional information: the materials and techniques used in the artwork, previous efforts in restoration, and fading or darkening of pigments. It all culminates in one thing: “Understanding what the work may have looked like when it was originally painted,” said Dr. Eremin.

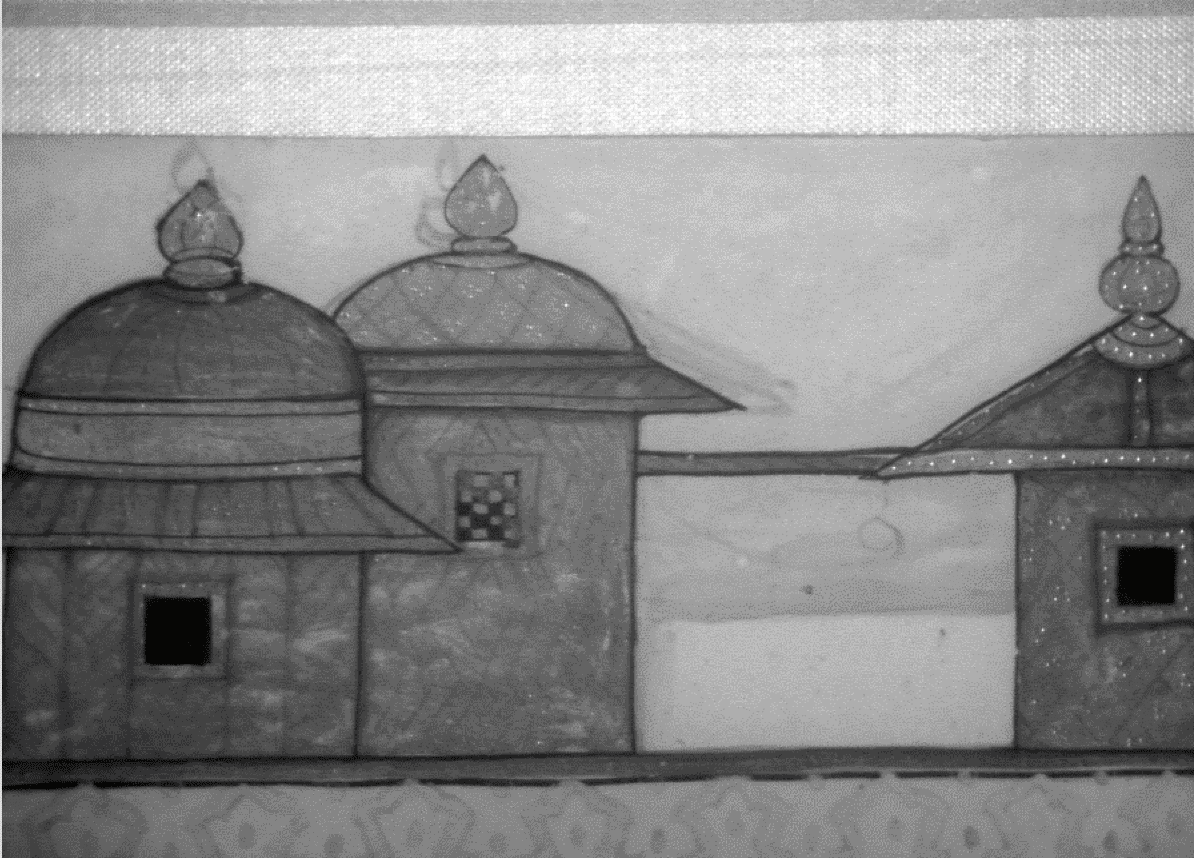

Using infrared spectroscopy, the Harvard Art Museums team is able to discover hidden changes to the buildings. This image shows a close-up of Image 1 cited above, “A Nayika and Her Lover: Painting from a Rasamanjari Series (A Bouquet of Delights). Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museums.

But the work analyzing the makeup of these paintings goes beyond the field of conservation and restoration, providing deeper insight into the region’s history. “We found that mid- to late-seventeenth century manuscripts contain smalt, which is an indication of trade where the import of the pigment probably comes from Holland through the Dutch East India Company,” Dr. Eremin said.

Together, Professor Kim, Dr. Eremin, and their teams will continue to unlock the secrets beneath these centuries-old Indian paintings, learning more about the working practices of the artists, the best ways to preserve and restore these paintings, and learning some history while they’re at it, too. With their ever-expanding expertise, their work will continue to deepen the understanding of South Asian art, allowing them to pass on their knowledge to others and broaden the scholarship of this critical body of work.