This week, the Visiting Artist Fellows’ Fall 2019 exhibit, Exploring Identity Through a Contemporary South Asian Lens, opened at the Mittal Institute. Available for viewing through November 26, photographer Sagar Chhetri and sculptor Sakshi Gupta unveiled their artistic interpretations of life, time, and the human condition to a rapt audience. The 8-week Visiting Artist research program provides a vital platform for an exchange of perspectives and knowledge, linking Cambridge and South Asia through shared stories and new understandings and providing artists from South Asia the opportunity to use Harvard’s resources to perform research that will inform their art practice.

“This program provides a precious opportunity for the Harvard community to engage with artists from South Asia and learn from the diverse perspectives that they bring. In turn, South Asia-based artists who are selected for the fellowship have the rare opportunity to engage with the academic community at Harvard and its intellectual resources,” said Professor Jinah Kim, Faculty Director of the Mittal Institute’s Arts Program. “The aim is to create a channel for communication and interactions that will inspire both the members of the Harvard community and the artists from South Asia.”

At the Still Point of the Turning World

Showing their artwork, the artists commented on their careers, inspirations, and the processes and thoughts that went into each piece. Sakshi works with found objects, reinventing narratives for the items she discovers in her series At the Still Point of the Turning World. “She creates new meanings and contexts out of what we would normally consider waste,” said Professor Kim. “In her work, Sakshi explores the need to achieve a balance between life’s inherent polarities. She wants you to stop in your tracks and really consider your own being and surrounds and your sense of self.”

Sakshi, a sculptor from Mumbai, explored residency spaces throughout India after completing her education in 2004. “These residencies were very low budget, and compelled me to look at material around me. I would find material outside my working space, bring it in, and transform it,” Sakshi explained. “This period changed my approach to my practice, as well as my experience as a sculptor. During these residences, I decided that this is what I want to pursue for the rest of my life.”

Sakshi showed the audience images of her sculptures in her studio space and in galleries, describing the materials used to create pieces that comment on something much larger. “When I came back home, I made visits to industrial scrapyards. I was quite taken aback by the sheer volume of the things coming out, and how beautiful they were. I couldn’t resist it, I needed to bring [these pieces] into my studio. It was like I was building a relationship with them. They came with a history of their own. We got familiar with each other — it was like building a conversation with these materials,” she said.

Motioning to the image above, Sakshi showed the audience one of the first pieces she ever showed in a gallery space. “As you can see, it’s like a ceiling fan coming down toward the floor, made entirely of industrial scrap. It was premised around the notion of transformation, and how it can be quite chaotic and painful in some ways,” Sakshi explained.

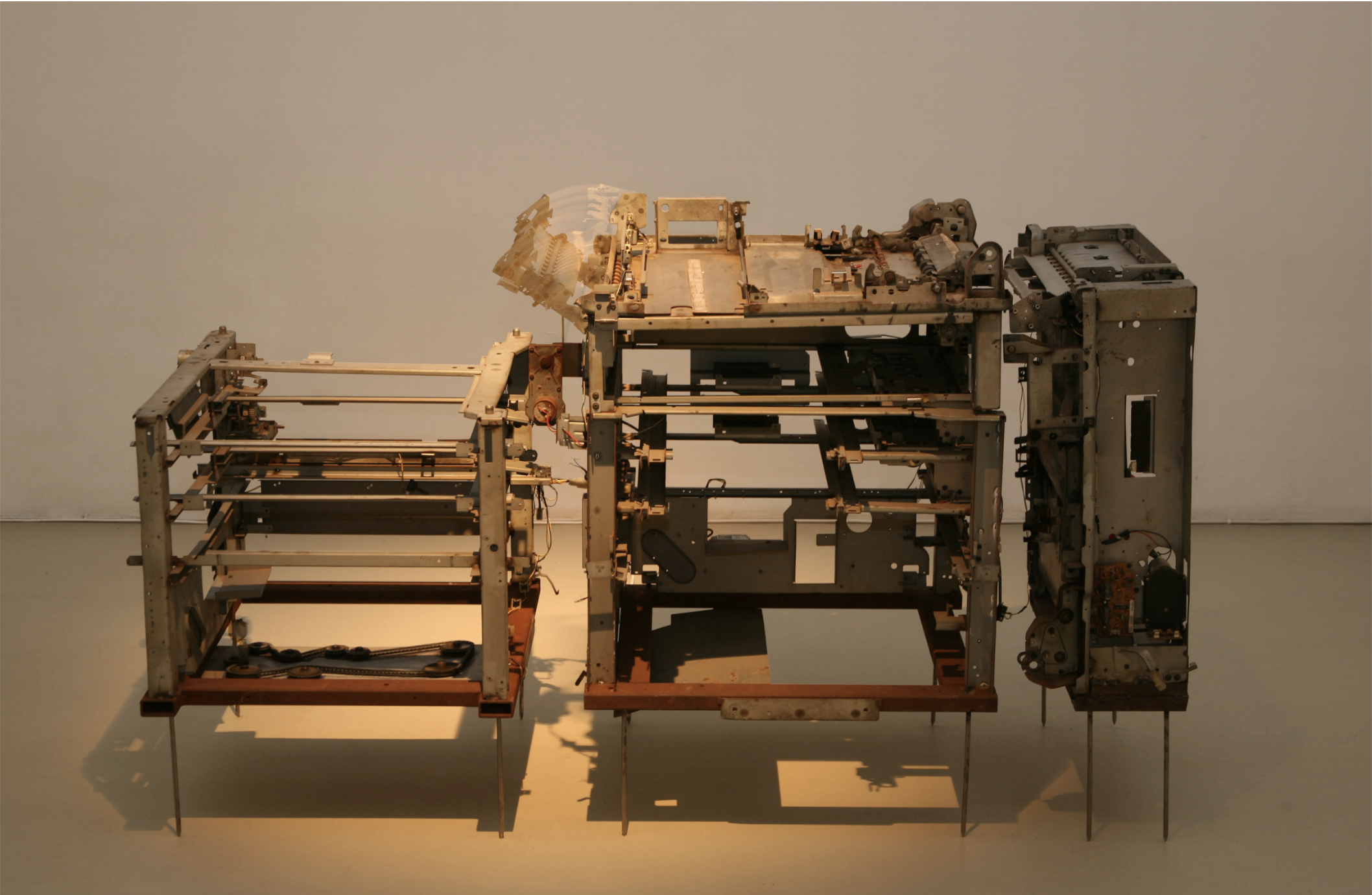

“This was another work I made, in which I actually found a Xerox machine in a scrapyard in Delhi. It was made in France — a 30-year-old machine. I brought it into my space, emptied it out completely, and got it working in different places. But it wasn’t functional, it wasn’t productive in the way we think of productivity, or the way a machine is supposed to function. So, again, I was challenging notions, asking: ‘What does it mean to be full, versus useless?’” Sakshi said. Her focus on change and transformation is intricately intertwined with the city of Mumbai, a dynamic and ever-changing place. “I think these materials that I find in the scrapyards or on the roads of Bombay, they’re constantly undergoing changes and construction,” she explained to the audience.

At Harvard, Sakshi will delve even further into her medium, understanding how she can look at the materials she finds through different lenses. “I want to look at things like time, space, and value through materiality. Coming from South Asia, it’s all the more interesting, because a city this old is still going through much change — and that has a heavy influence on my work,” she said.

Eclipse

Sagar grew up in the southern belt of Nepal, along the Indian border. Through his photography, he works to capture the essence of the region, exploring the character and strength of the people who live there to understand the deeper fabric of the Madhesi community. “Sagar brings a different sense of Nepal’s geography and demography,” explained Professor Kim. “He’s been actively involved in raising the visibility of a marginalized group of people of his native homeland, the Madhesi. His recent and ongoing project, Eclipse, explores the ambiguity that exists around the identity of the people of the Madhesi.”

For the past 10 years, Sagar has lived and worked as a full-time photographer in Kathmandu. “In 2015, I was part of a team that was organizing the first photography festival in Kathmandu,” he explained. “There was some political upheaval going on at the time, a Madhesi uprising on the southern belt of Nepal. I thought it was the right time after the festival to intervene as an artist, a photographer — to go to a place and do something about it.”

When he arrived, he began photographing the activities that were going on around him, trying to get a sense of what was happening. “It was a terrible time. My work, Eclipse, is about ambiguity and the identity of the Madhesi people. I’m also trying to look at how the border region has become politically salient, highlighting the political grievances of the people. But after photographing the street for some time, I felt that this is not what I should be looking at — I should go deeper and invest more time in this project,” Sagar explained.

“I started to turn my lens toward the villages, and went deeper into the fabric of the city and its daily activities. I met people, had food with them, staying open-minded and photographing down the road, reflecting the feeling inside of me that was being generated by the activities going on around me,” he said.

“As a photographer, I’m very much interested in making photographs that are not obvious, that are subtle and give you a hint of the situation around them,” Sagar said. Indicating the photograph on the left above, Sagar described his interaction with the subject. “The moment I saw him, he was bringing a few things around, and he was covered with mud. As an artist, I was interested by the mud on his skin. It resembled the earth, which I was trying to understand. I wanted to take a portrait of him, and asked if I could. He was looking at me with his eyes wide open, but I was using a flash, and thought it might hurt his eyes. I told him he could close them, but he still wasn’t trusting me, so he kept one eye open. The earth, one eye open, one eye closed — I felt there was something there when I saw the photo,” he explained.

Together, the two artists bring to light the fabric of their respective societies, the underlying feelings and identities of those who live around them, exploring how a material, once part of someone’s daily life, can tell a new story, or how looking into the eyes of a rebellion can help understand the character and struggles within. To see more of their artwork, visit the Mittal Institute to view their pieces through November 26, 2019.