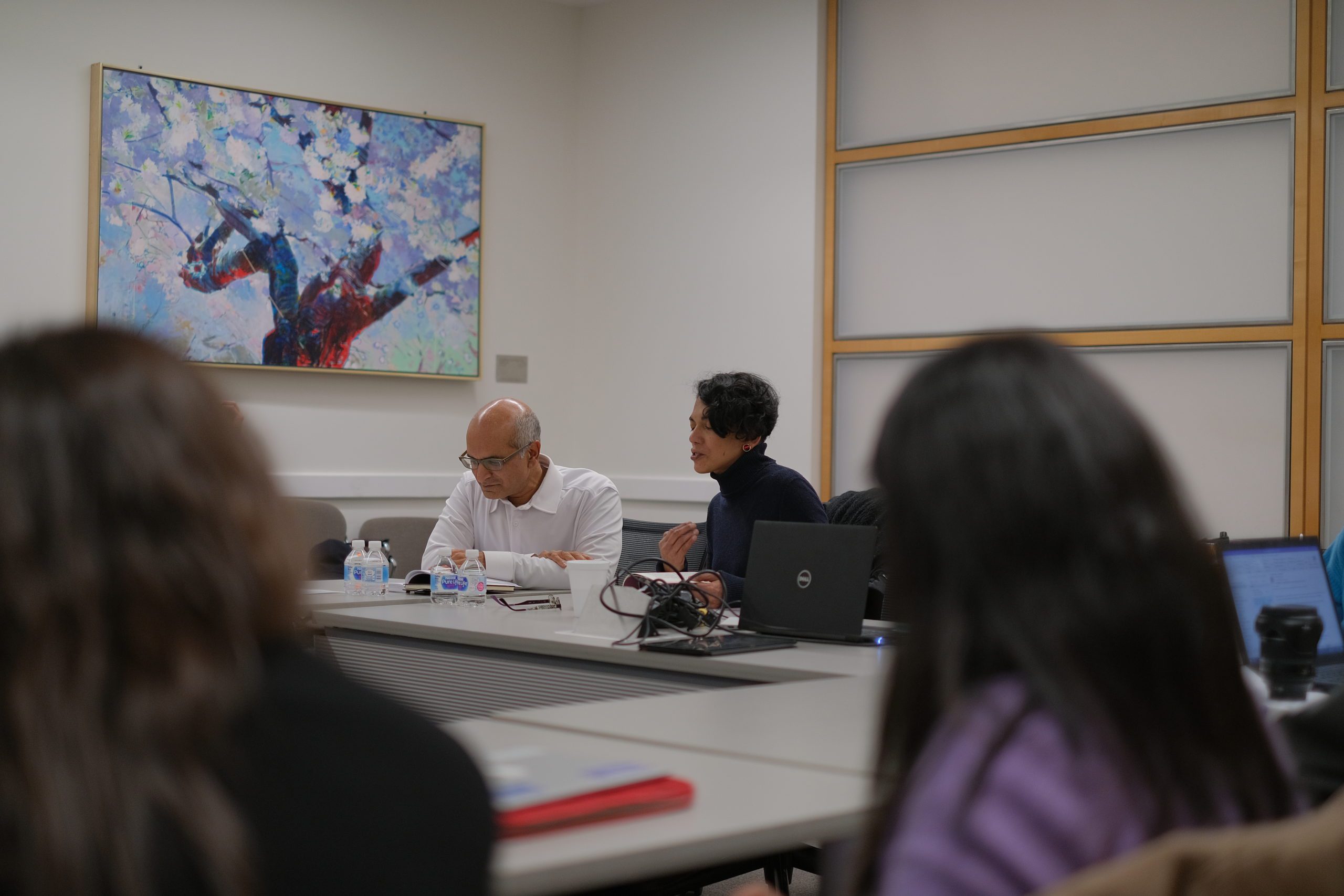

Earlier this week, we were joined by Karthika Naïr, author and poet, for an in-depth discussion on her latest book, Until the Lions. In the book, Naïr retells the story of the Mahabharata through the embodied voices of women and marginal characters. In conversation with Professor Parimal Patil, Professor of Religion and Indian Philosophy at Harvard University, and with the audience, Naïr brought these voices to life.

“Chinua Achebe cited a great proverb once: ‘that until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter,’” said Professor Patil, opening the conversation and highlighting how the minor characters in our history can often get left behind. “Once I realized that, I had to be a writer. I had to be that historian. It’s not one person’s job, but it’s something we have to do — so the story of the hunt will also reflect the agony, the travail, the bravery, even, of the lions.”

Naïr’s book introduces us to 19 of those lions from the Mahabharata, who each have a voice and place in the original epic. “The lions include a range of characters whose presence looms large in the epic, but who usually speak in whispers. The strength of their voice comes not from what they actually say, but from what they don’t say, and what the impact of their presence is,” explained Professor Patil.

In the series of poems in Until the Lions, Naïr chose to weave in one voice in particular throughout. “There is one voice that binds them all together a bit, and this is the voice of Satyavati. There are many perspectives that come into the book, some of which contradict, some of which complement each other, and each of which is real and personal to the teller. And Satyavati herself reminds us through the book that her story is not necessarily a factual one, that she would obviously be looking after her own interests as well,” said Naïr.

As Until the Lions builds on the narratives of these marginal characters from the original epic, we gain more insight into the story itself. “We learn so many things about the Mahabharata narrative as it’s normally received that we didn’t know before,” expressed Professor Patil. “For example, we learned that it was Satyavati and not her father who struck the deal regarding whose children would continue and have the chance to be king.”

“However familiar you are with the Mahabharata, there are things you forget,” Naïr said, commenting on Professor Patil’s observations. “There are people that you don’t necessarily know all of their actions, which may have been catalysts for other actions.”

Naïr and Professor Patil welcomed discussion from the audience, and one participant noted, “This is something that I think a lot of young women today want to do, is start to bring out these voices, and start to retell stories. How do you tell these stories with few sources to go on? What does the process look like to actually write this story?”

“I’d actually say there are a whole lot of sources,” said Naïr. “It depends on what you call data. There’s a Javanese Mahabharata, there’s a Persian Mahabharata — there are so many tellings that have been part of the great tradition of epics, and very little is invented. Everything’s had a source which I found in an interstice or in a certain language tradition.

“There’s always been a spark somewhere, and I think that’s very rich. For me, it’s a danger today to think that there is actually one monolith epic — that there is a single narrative. Because there never was.”