By Siva Emani, Harvard College ‘21

Over the last three weeks of my winter vacation, I traveled to Hindu temples throughout South India, with the goal of understanding the inspirations and motivations that drove musicians to compose about the idols worshipped at these establishments. Starting from the Eastern temple city of Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu, I snaked along the Eastern coast of the Indian peninsula, ultimately arriving to the country’s southern tip at Kanyakumari, before continuing through the hill stations of Kerala and ending at Guruvayur, Kerala.

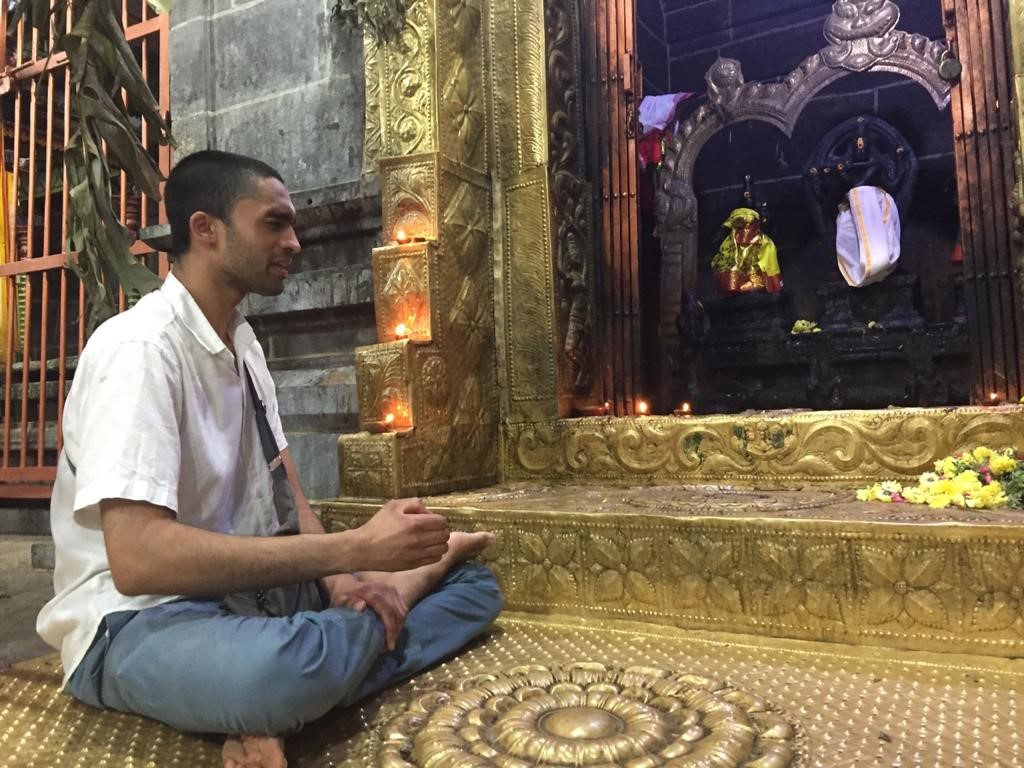

Throughout the journey, I almost exclusively visited places of worship for Hindu practitioners, the trip being both a research trip and a sort of personal pilgrimage. I would rise with the sun in the morning at around 5:30, showering before dressing in a pattu panchi (silk garment) and applying to my forehead the marks of vibuthi (potash) and kumkuma (red colored turmeric) customary of temple goers. After performing a daily worship exercise, I would visit the temple. Due to limited time and an ambitious itinerary, I focused on the one or two major temples at every city I visited, often visiting a temple twice for a total of three to six hours in each temple complex. I primarily visited temples that inspired musical composition of four major composers in the South Indian Classical tradition — Thyagaraja, Muttuswamy Dikshitar, Shyama Sastry from Tamil Nadu and Swati Tirunal from Kerala. For almost every temple, I learned a song and studied its meaning extensively, before singing it myself at the temple in front of the main idol, with the hope of tasting through practice and observation the feelings of devotion and surrender which the composers themselves felt moved to describe through poetry and music.

I could write volumes about each temple I visited, and the different perspectives which I feel each temple has to offer, but I will highlight a few observations and experiences. The temples in Tamil Nadu radiated a certain grandness, as if shouting, “God lives here,” with the stony thunderous voice appropriate for such a statement. Extravagant temple complexes were decorated with multistory gopurams (gateway structures), giving way to multiple layers of inner corridors, full of ancillary shrines, basking in the glory of the main idol. The Garba Griha (inner shrine complex) was usually enclosed, containing the main idol surrounded by a single corridor for circumambulation, with intricate carvings of stories adorning the hefty single-stone pillars that supported these architectural masterpieces. The circumambulatory path to the central sanctum would often contain shrines for other Gods and Goddesses, and often a tribute to the Tamil Azhwars and Nayanmars saint-poets who are often revered as members of the pantheon themselves.

The shrine to the main deity usually utilizes natural lighting from fire-lit lamps to produce a sort of warm glow to the black-stone idols, as if the devotee is praying to both the God and to the God’s manifestation as the element of fire itself. Often, the main moola vigraham (founding statue), made of stone, finds its origin in the Hindu puranas (a set of story texts), with a smaller golden replica in front, used for Ureygimpu (ritual processions). Offerings are given to the idol regularly — milk, fruits, ghee (clarified butter), clothing, vibuthi — and then given to devotees in the form of prasadam (food offering).

The temple complexes in Srirangam and Madurai serve as prime examples of this grand architectural paradigm. The towering gopurams can be spotted from kilometers away, causing pilgrims to feel the occasion of their arrival with a certain pomp and ceremony. With many sets of enclosures, the temple complex acts as a sort of small city, the first few rings bustling with marketplace drama — street vendors selling light up toys and women purchasing malli puvu (Jasmine flowers) to wear in the traditional Tamil hairstyle. Cities such as Madurai were built around the temple complex, with ritual circumambulation emphasizing that the lives of the citizens revolve around Meenakshi Amman, the Goddess who lives there. Srirangam served as a hub of philosophical and scientific inquiry in addition to devotional practice, with the wonder of scientific discovery associated almost instinctually with the wonder of creation. The offerings of fire, rice, milk and even the temple complex itself would have been significant, as they were the greatest advances in human technology, they were all humankind had to offer.

In this culture of complete societal surrender to a single source, it seems inconceivable that the arts would not also praise the entities to which the kings themselves bowed their heads. A song by Muttuswamy Dikshitar, Rangapuravihara (he who lives in Srirangam), portrays this feeling of ecstatic wonderment consistent with the grand temple architecture in Srirangam. A slow brooding tune, the song sways slowly to a melodically minor ragam (musical mode) where the Lord is hailed as “brindavana sarangendra” (king of the animals).

The Arunachaleshwara at Thiruvannamalai, as seen from Ramana Maharshi’s Skanda Ashramam. Photo by Siva Emani.

Temples in Kerala boast a very different relationship with the divinity that they house. They are often smaller, austere complexes, one-story buildings with low, slanted rooves, akin to a Japanese-style architecture. Unlike the stone fortresses of Tamil Nadu, Kerala temples often are built of wood, giving them the feel of a cozy New England cottage, confused by seventy-degree heat in the winter. Despite their small stature, they are often highly decorated and filled with coffers of gold offerings to the Lord. The Padmanabhaswamy temple in Thiruvanantapuram had a modest exterior, but contained golden pillars decorated with stories from the Bhagavata Purana in the inner sanctum. Guruvayur’s temple complex was adorned with paintings in the Kerala style — colorful, voluptuous figures reveling in palace mirth or revering the Lord in a sort of personable form. Songs composed about these deities often mimic the quaint ornateness of the temple architecture. Tirunal’s composition “Saramaina matalento” rebukes the Lord for speaking coyly to the speaker and asks Him to listen to the pleas of His devotees. Employing the pleasant almost jumpy ragam of Behag, the song illustrates a playfulness of the Lord, embodied by his relaxed, supine pose as Padmanabhaswamy in Thiruvanantapuram.

The distinctness of the temple architectures symbolizes a diversity in the forms of worship of Bhagavan (the Lord), inviting him with pomp and ceremony on Srirangam’s red carpet or nourishing him with love and affection in Sabarimalai’s humble cottage. This relationship is reflected in the classical musical tradition, but also in the way bhaktas (devotees) relate to the idols today. The desire to take darsan (sight) of Bhagavan serves as a powerful calling for pilgrims all over the world, standing in 4-hour queues for a glimpse of the vague outline of a face, barely lit by a flickering flame.

It strikes me that the same desire to be amazed, the same flavor of wonder at creation that inspires musicians, scientists, and naturists, must also inspire the bhakta to be moved not only by something like an idol, but by what it represents. As much as this trip taught me about Hindu fine arts, I also learned that the openness to profundity, the ability to be intensely impacted by experiences has less to do with the experiences themselves and more to do with how one approaches them. The practice of bhakti for the great architects and composers seems to be something of a heightened sensitivity to beauty in a normal everyday world, and an attribution of that experience of profundity to something greater than the self or mankind. Rejuvenated in my faith and in my curiosity about the traditions and philosophies of ancient Hindustan, I am extremely thankful to the Mittal Institute for giving me this once in a lifetime opportunity for research and self-discovery, and I look forward to learning more about myself and the relationship between human and the divine through future studies and research.