Numair Abbasi, a mixed media artist from Pakistan, recently joined the Mittal Institute in the latest group of Visiting Artist Fellows. Numair’s practice draws on popular culture, anecdotes, and colloquialisms to stage personal and social narratives in attempts to challenge the politics behind how gender is socially constructed and performed.

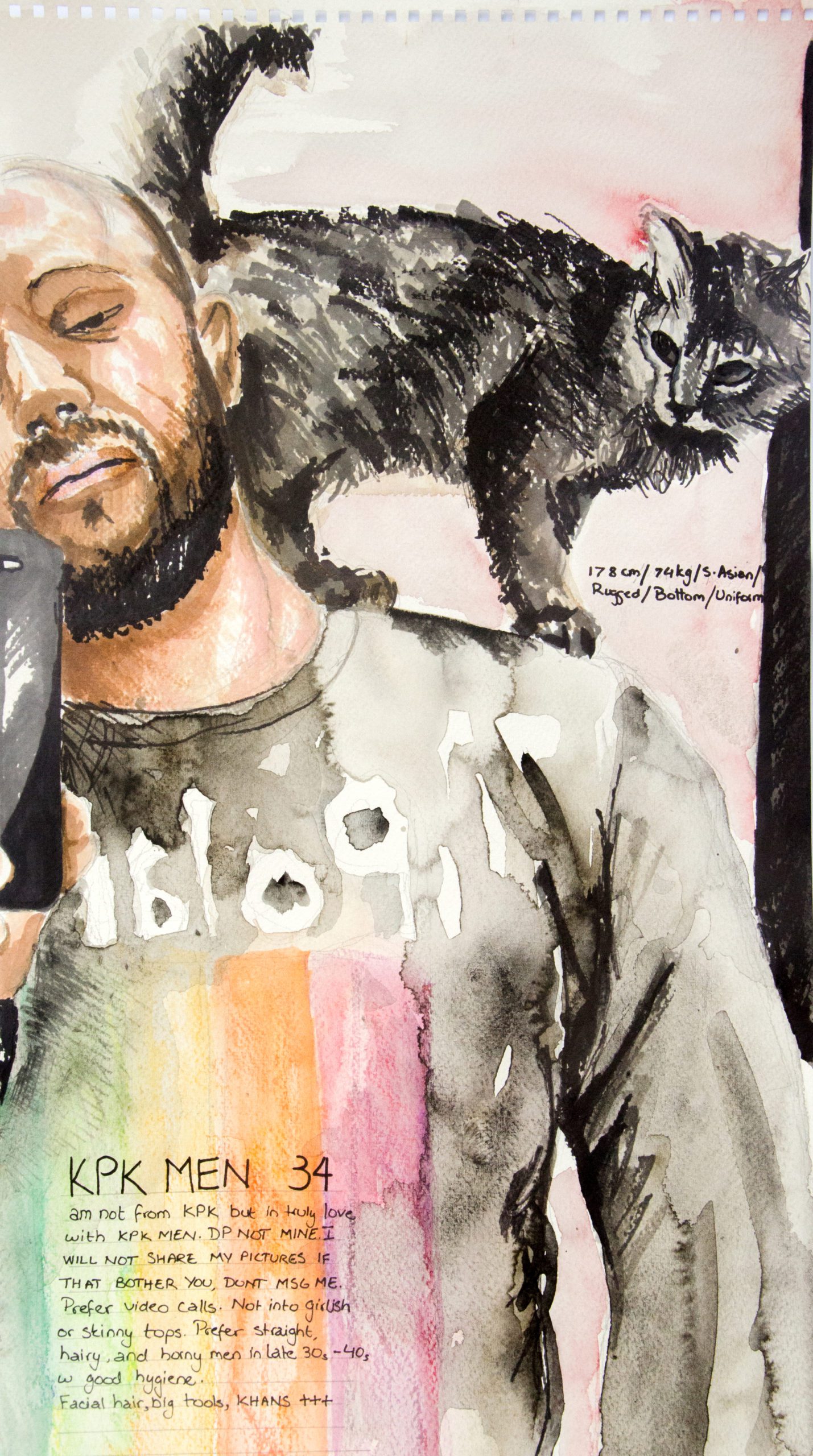

Recent turns in his practice observe how queer men navigate issues related to their identity during interactions within and beyond the community, and across domestic, public, and virtual environments. He repurposes dating apps to investigate the dynamics of fragile spaces where interactions are dislocated, ephemeral, and motive-driven.

We recently sat down with him to learn more about his background, his artwork, and his thoughts on gender identity in South Asia.

Can you tell me about yourself and what inspired you to pursue art as your career?

I come from a family of lawyers, engineers, and doctors. My brother had a very strong creative flair, he was very into art. I wasn’t good at it, and I think I was quite envious. I started to pick it up and, later on, it was I who pursued it. When my brother wanted to become an artist, my parents shot it down, so he decided to become a plastic surgeon. But I knew I wanted to do something related to art, fashion design, or architecture, and eventually picked up architecture because it was perhaps more palatable to our parents.

Those in their first year of art school take a foundation program where you run through all sorts of disciplines. Textiles, graphic design, and so on. I did not enjoy the architecture assignments we had — I found it a bit too dry. At the end of the first year, I decided that I was quite enjoying art and was going to go into that. That’s where I made the transition and never looked back. I quite enjoyed it, the process of conceiving an idea, the tactile nature of working with your hands, and how it was like visual poetry, interpreting something the way you see it. All of these elements are why I went into art.

What are you trying to convey through your art? Are you trying to challenge or comment on something?

I think that comes with everyone’s work, where they’re trying to change or challenge something. I’m not trying to send any message in my work. Primarily, I’m a storyteller. I just try to share my experience and my stories and these anecdotes — these quirky, unusual instances that I hear of or have witnessed or experienced, and that informs my work.

I think that message and that awareness comes with it, but never have I actively thought that my work is to bring about change in society. I’m just sharing my story, and how I see a particular situation. If it makes you think or question something, that’s great. As long as it brings about a conversation, it’s working. That’s what most important.

What kind of stories are you trying to tell?

Initially, I was quite short-tempered as a child. Physically, verbally abusive to my parents — I don’t know why, I can’t trace it back. One of the points where I was going through this phase was when my mother was battling breast cancer. I remember for my thesis in my last year of school I wanted to work with that memory, kind of an apology. But at the same time, I didn’t want to work with someone else’s trauma — that’s not me.

One of the things I always remember is one of my teachers saying that, as artists, we are always sensitive to either our own or someone else’s pain — and to just take the characters out. Take the characters out and talk about the emotion. Talk about whatever they’re going through so it becomes more relatable to everyone else, and doesn’t have to be about your mother. Whenever you look at the work, it will probably be about your mother, but no one else can tell.

That’s where my work began to get into this idea of human relationships and emotional baggage, and how we carry baggage of our own or someone else’s through these strenuous relationships that we build over time through our identity. For me, being a closeted gay man — and in hindsight perhaps that’s what I was dealing with and why I was acting out — I was considering how that identity puts this weight on your shoulders. So, my initial work went in that direction.

As I got braver and braver working, that’s when I decided to really question things: why am I treated the way I am? Why does my family expect me to be a certain way? Why does society expect me to be a certain way? Why do men have to be stoic? I don’t know how it happens globally, but in South Asian societies, men are recurrently reminded of their status as the provider to their family, and I contest that.

I began to get into the question of what really is a quintessential male in Pakistani society. What is masculinity? There’s not enough conversation that goes on about it. We talk about women and the societal pressures they go through, but I don’t see that conversation happening at all for men.

When I started to make these nude figures, the response that I received is also what propelled me to pursue it further. It’s somewhat global that we have an appetite for female nudes, a general acceptance of it. But you don’t really see that regarding male nudes — in Pakistani society, not at all. I’ve had some of the most absurd comments said to me by collectors, by buyers, by passers-by regarding male nudes, and that made me question: why do they see it that way? Why are they reacting to a particular work that way? I think that’s quite essential, most people don’t go a step further and ask themselves: why am I responding that way? But the answer to that tells you a lot about you and how you process things. I really relish what response I get, good or bad, because it gives me a peek into your mind.

You’ve noted that aspects of your work “investigate one’s performative versus their real in everyday encounters and in personal living.” Can you elaborate on this?

What I’m currently working on now are conversations — intimately speaking to people. I’m looking into real-life conversations and those moments that I’ve shared with people where you do feel intimate with them. Another subject that I occasionally read into and am quite fascinated by is our real selves versus our performed selves. On [dating] apps, are we our real selves, or are we performing? Is it the space that is dictating how we navigate around, or are we capable of taking hold of the platform ourselves? Or is that our real selves, and how we interact in real life is that something that we’ve learned? Is that something that’s choreographed?

I was talking about this with a gay, older friend of mine, and he responded by saying it’s because we as a generation in this time like to consume visuals. You have professors putting memes in their presentations, you have Instagram, and you have Tinder where the first thing you look at is an image. He talked about this old application, a chat forum similar to MSN called MIRC. At that time, you couldn’t send images to each other — so how do you remember someone without an image when you’re speaking to many people? So, to remember someone, they had to have a meaningful conversation.

You mentioned that you’re looking to learn more about the construction and performance of binary genders and sexualities in South Asia as consequences of colonization. What do you know about this already, and how has this impacted your work so far?

Initially, I used anecdotes to inform my work. But this idea came about when I read an advertisement on the metro in London, which listed different non-binary identities from developing countries. From Africa, from the Philippines, Peru, and so on, it said that non-binary identities have pre-existed colonization. That is something that stuck in my head.

In Pakistan, a lot of people think that this non-binary and binary conversation is a western import. But we’ve heard of many Sufi poets who had same-sex lovers, and Mughal emperors and others in authority had relationships outside of marriage — and they didn’t have any labels. There was no awareness of it: what is bisexual? What is straight and gay? They didn’t know any of this, they were fluid and free. You have these Mughal emperors who are wearing these A-line gowns with heavy floral embroidery and jewels and henna on their hands and mascara on their eyes, all of these things that we now consider feminine, and yet they’re fighting wars and running empires, which we consider kind of masculine. So, there’s a dichotomy, but they had melded it together.

I was quite curious as to why and how we ended up defining what masculinity and femininity is, and what they are really influenced by. I used to have a kurta in every possibly color, I had a whole spectrum in my closet — four shades of red, three shades of yellow, and so on — and I would arrange it like a rainbow. And there were all of these comments that would be passed around about me, that I’m effeminate and flamboyant, and that made me question: who is defining all of this? What counts as flamboyant? What counts as feminine?

I wanted to bring that conversation into my work: where and how these perceptions have been influenced. Let’s say by colonization — which I think is one of the sources, but I’m sure there are other influences, like religion, that probably had a play in how we perceive gender, masculinity, and femininity. It’s something I’ve been interested in for a long time. Where did fem-phobia come from? It’s very prevalent around the world; at least in the gay community, it’s an active notion, along with the idea of what masculinity should be and what the ideal body should look like. These are things that I want to question. I do want to share my apprehension over the subject: this is something that leaves me a bit confused. If it instigates a conversation, that’s a bonus.

What do you hope to learn or experience during your time as a Visiting Artist Fellow?

I’m not much interested in academic theories — coming from South Asia, the language of theorization itself and art criticism is very colonial, so I don’t really believe in picking a theory up and implementing it into a completely different region, one that’s still trying to develop its own history.

But what I do love about these experiences are the anecdotes that come up, perhaps sitting with a professor and talking about my work and hearing the narratives that they bring up. That’s what is going to inspire my work. For example, two years ago, I was applying to something in Iran. We always hear about how the clothing of Iranian women is policed, and I became curious about the men. For men, shorts are discouraged in public spaces. I just found that so fascinating – why have we not heard about men being discouraged from wearing shorts? Why has it always been women that have been the focus? These bits of information are what really fascinate me, and the visual and idea gestates and comes about.

—————————

☆ All opinions expressed by our interview subjects are their own and do not reflect the views of the Mittal Institute and its staff.