By Divya Chandramouli, PhD Candidate ‘22

For my dissertation project, I hope to trace the stories of Tamil drama artists, as they traveled, performed, and lived between 20th century Madras Presidency, Ceylon, and British Malaya. This winter, I went on a research trip to Madurai and Chennai, Tamil Nadu, to understand the infrastructures that supported these artists’ travels, as well as the kinds of performances they held abroad.

This winter, a research grant from the Lakshmi Mittal South Asia Institute enabled me to spend a month in Chennai, India, for preliminary dissertation research. I arrived in Chennai on December 18th, after having spent a week in Colombo, Sri Lanka, for a conference.

My first task in Chennai was to get reacquainted with scholars who I had been in touch with during my last trip. As my project has evolved over the last year, I wanted to meet with other scholars to get their insight into the types of sources I would be able to access in Chennai.

I met first with Professor A.R. Venkatachalapathy, a scholar of the Tamil Dravidian Movement and 20th century Tamil writers, who directed me toward valuable Tamil primary sources — particularly, the autobiographies of drama artists that I had not been able to trace thus far.

Professor Venkatachalapathy also provided references for Tamil scholarship on cinema and theater. Since I’ve worked almost exclusively with English scholarship on the subject until now, these Tamil sources may greatly expand the range of questions and arguments I engage with through my research.

During my trip, I also met with dramatist and theater scholar Professor Mangai, who redirected some of my driving questions so that they better reflect the historical context of theater in Tamil Nadu. For instance, rather than asking: “What were the differences between so-called urban, ‘amateur drama,’ and rural drama?” Professor Mangai nudged me to question why and on what basis I may be demarcating urban and rural drama from one another to begin with.

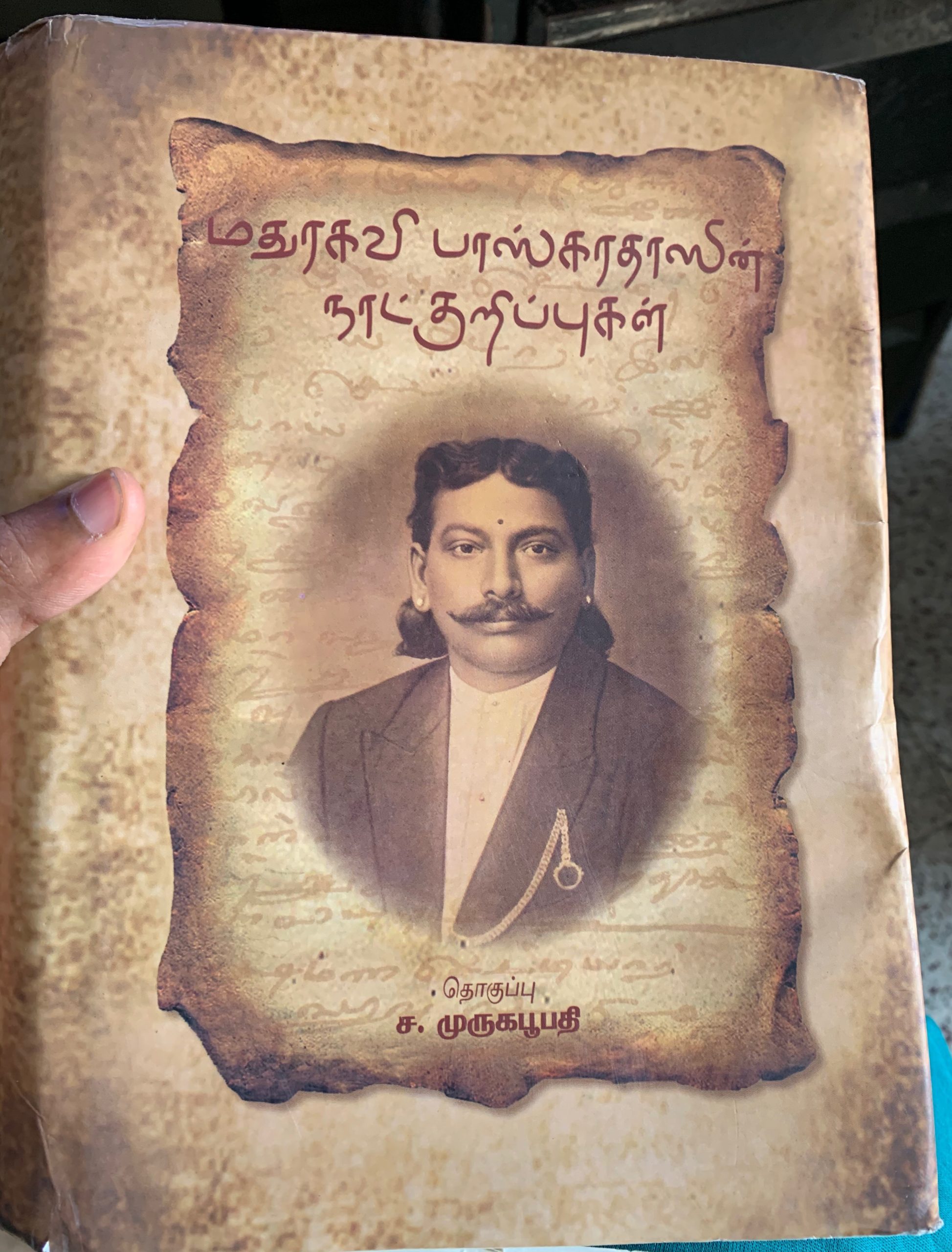

Over the last few days of my trip, I met with Professor P. Ahilan, who was visiting Chennai from JNU. As we meandered through Chennai’s annual book fair together, Professor Ahilan helped me find a source I’ve been searching for since 2018: the diary of a traveling drama artist, published by his grandson. The insight and generosity of Professors Venkatachalapathy, Mangai, and Ahilan has allowed me to discover and begin to contextualize a number of Tamil sources I may never have heard of otherwise.

Diary of a drama artist. Photo by D. Chandramouli.

Aside from these conversations, my time in Chennai consisted of visits to the Roja Muthaiah Research Library, where I was able to find drama scripts and advertisements from the 1930s and 1940s.

I copied down the dialogues for a handful of plays (storing them in my notes to analyze later), but was particularly interested this time in the illustrations that accompanied some of the dialogue pamphlets: How was the stage represented on paper? How were stage characters portrayed on paper? How might this have compared to the costumes of actors, or the stage backdrop?

In other words, I began to wonder which overlaps lay between representations of the stage on drama advertisements, and the stage itself. How did the stage come to be imagined and incorporated in contexts outside of drama?

I also attended dramas put on by renowned stage actors, including S.V. Shekar, Y.G. Mahendran, and T.V. Varadharajan. As a researcher of 20th century Tamil drama, it was fascinating to try to understand how modern-day drama artists make their performances relevant to contemporary audiences, even if the scripts were written decades ago. Each of the dramas wove in references to political and social themes emerging around us, whether that included the sky-rocketing costs of living in Chennai, the CAA bill proposed by Modi, and the complacency of corrupt politicians.

Almost all of the dramas I attended echoed the question, “What has this world come to?” and several lamented the fact the “justice” or “truth” stood silently in a corner as injustice flourished freely. These performances gave me opportunities to reflect on the space that is created by drama: What work is done by these dialogues, which lament the current social and political state of affairs? How do they bring audience members together? How do they provoke (or not provoke) action and reflection? After the performances, I was able to speak to some of the drama artists and get their contact information to schedule longer conversations, which will hopefully take place during my summer visit to Chennai.