Suhasini Kejriwal, a mixed media artist from India, joined the Mittal Institute earlier this Spring in our latest group of Visiting Artist Fellows. Through photography, paintings, embroidery, and more, Suhasini’s practice acts as witness to the lived experiences of those whom she observes, living out their lives in the busy streets of India’s urban landscapes.

We recently sat down with her to learn more about her background and the context behind her artwork, and how she brought art to the streets of Chitpur to make passersby stop and think, bringing a new source of curiosity to their lives.

Can you tell me a little bit about yourself and what inspired you to pursue art as a career?

My earliest memory of drawing is as a child sitting on the floor in my room and scribbling with crayons on the large piece of paper under me. I remember it being a sunny morning and the light pouring in through louvered windows, making warm stripes on the deep red floor. I remember being happy and drawing until the drawing had escaped the edges of the paper and covered the surrounding floor.

Drawing and painting were integral parts of my childhood as I grew up in Calcutta, but they were only some of the many things I did, along with riding, swimming, playing the piano, and learning Hindustani classical music.

Growing up, I didn’t actually think that either art or writing could be a viable career option, so I applied to study Mass Communications at the University of California at San Diego. While there, I mostly chose fine art and music classes, and one of my teachers told me that I had a temperament more suited for fine art rather than media and advertising; this was all the excuse I needed to formally switch over to a major in Fine Arts. I wanted to immerse myself completely in an art environment and went on to complete my undergraduate studies at the Parsons School of Design in New York and my postgraduate studies at Goldsmiths College, London University, with time spent in my studio in Calcutta in between.

When I came back to India, they weren’t many young artists in Calcutta engaged in a dialogue with each other, let alone contemporary art, so I worked in my studio in quiet isolation. Although I found this challenging, I was lucky to have the steady support of a good gallery and the opportunity to show both nationally and internationally.

As a student in a foreign environment, I was naturally interested in identity politics. Most of my early work in college explored issues around representation and finding an authentic language in painting that felt true to my background and experiences. At the same time, I was also immersed in the learning process at both college and the shows I saw in galleries and museums. I remember, in particular, a comprehensive exhibition on Surrealism at the Victoria and Albert Museum that also had on display many objects and theater props that captivated me.

I was deeply influenced by surrealism and had always loved nature and plants, so I began making lush, fictional paintings and sculptures in a saturated palette and containing imaginary plant-human hybrids. I really liked making them in the beginning, enjoying their ability to absorb me wholly in their absurd believability. At this point, I had spent time in New York and London with reasonably long stints in Calcutta between the two, so I was never in one place for more than two years. The strange fictional world I had created in my work made sense to me in those shifting environments.

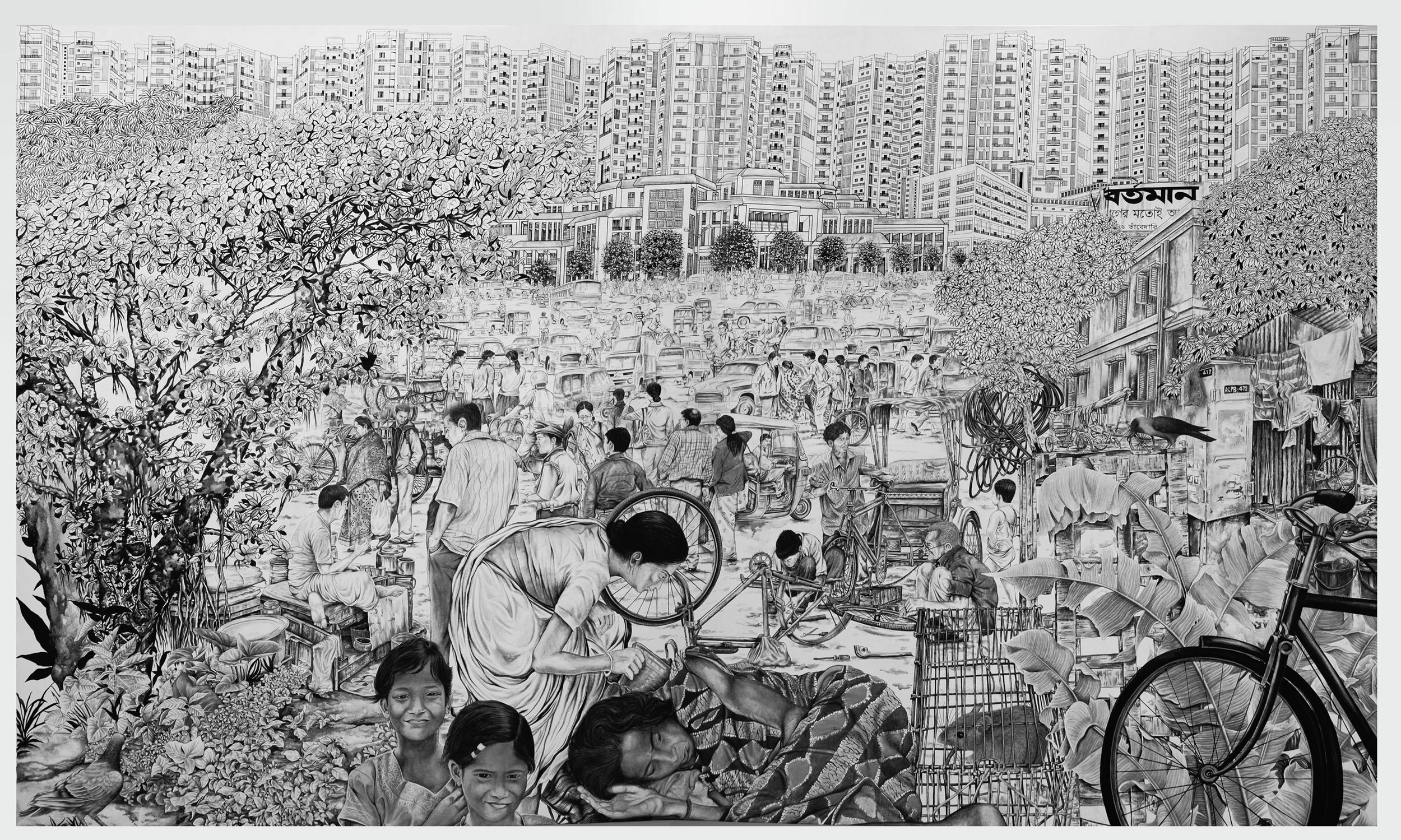

By 2007, I was back in India permanently after spending seven years abroad. The fictional world I had created and that inspired my work had slowly started making less sense to me and was getting replaced by the urgent density of my immediate surroundings. I was at once overwhelmed and fascinated by all the frenetic activity on the streets in my city. Everyday, en route to my studio, I would look out of my window and watch with wonder and amazement all the simultaneous happenings and activity on the streets. I was seeing things anew despite their familiarity.

I eventually began getting out of my car and taking pictures to make sense of this barrage of visual information. Drawings emerged from these photos and slowly grew into a sizable archive over the next few years.

This signaled a huge shift in my work, because I had turned my attention from a fictional, self-created world to the real world around me. I pared down the sensory overload of my saturated palette to simple line drawings in a bid to organize my thoughts. To convey the urgency and density of the city, I layered image upon image to create very large, complex drawings. Slowly, over a period of five years, the line drawings gained volume and fullness, expanding the scope of the line to grayscale.

Meanwhile, I began to feel the need to collaborate with others in an exploration of the city as a shared space. I asked my family, friends, photographers, and other visual artists to walk me around their favorite neighborhoods in Calcutta and Bombay. I walked through many neighborhoods and eventually found myself returning frequently to two: One was Chor Bazaar in Bombay, with a very famous antique flea market and an area for automobile recycling; the other was Chitpur, located in an old historic part of Calcutta. In British times, Chitpur was the home of the native elite and a hub for intellectuals, poets, social reformists, and judges, and others. It was known as the seat of the Bengali renaissance. The first modern educational establishments for Indians, theater, publishing, and printing flourished here.

Of all of the places that people brought you to, what is it about these two places that drew you in deeper?

When I first went to Chor Bazar in Mumbai, I had the feeling that I was stepping into a theater set — the old buildings, unusual antiques, and beautiful furniture had a striking quality about them. In smaller lanes off the main streets, the artfully arranged tire shops and piles of automobile junk surrounding carcasses of old cars were equally compelling. I had the same feeling when I stepped into the similarly surreal surroundings of Chitpur in Kolkata. Beautiful, crumbling buildings with their lace balconies provided a gentle foil to the bold, almost absurd, Jatra theater posters that dominated the streets.

Photographing both of these places over the next four years, I developed an archive of a few thousand photographs and drawings. As time went by, what fascinated me was the quiet invisibility of the people going about their daily lives in these picturesque, historic neighborhoods. Instead of just responding to the surreal beauty of the streets, I became aware of my role as an artist and a witness to the dramatic changes that reshaped Chor Bazar due to extreme redevelopment. In Chitpur, as part of a fellowship with the collective Hamdasti that was working in the neighborhood to create a platform for meaningful dialogue, interaction, and civic participation between artists and communities, I collaborated with a signage maker to produce a series of artworks that combined text with ready-mades. These were displayed and performed on the streets of Chitpur as artistic interventions in daily life.

Both aspects of this entire experience are important to me, because on one hand I was in control — watching, witnessing, recording, archiving, and making work — and on the other hand, I actually put my own work on the street, in the neighborhood, so that it became a more equitable engagement with the audience.

When you say you displayed and performed art on the streets, how was this done?

When I began to work in Chitpur, I wondered whether my engagement with the city could simultaneously linger on in the streets and public spaces. Was it possible to blur the lines between the public and the private spaces of making and experiencing artwork? During my fellowship with the collective Hamdasti, I collaborated with a local signage maker to combine text in metal with ready-made or found objects. Imbuing these objects with new meaning and placing them back within their contexts created curiosity and surprise, leading to unusual interactions between our collective and the audience on the streets. It gave me the unexpected ability to layer a landscape with new meaning.

For instance, our first intervention was on the noisy and chaotic streets of Chitpur, where buses, cars, auto rickshaws, cycle vans, and hand-pulled rickshaws jostle with each other for space. It consisted of text excerpted from a poem in Bengali by the area’s most famous resident, Rabindranath Tagore, made in brass, placed on the seat of a hand pulled rickshaw, and pulled along the streets by members of our collective, our community partners, volunteers, and locals. The second was an installation outside the beautiful, old building of Chaitanya Library, featuring another excerpt from Tagore’s Gitanjali in English. Tagore was known to use this library when he lived here.

The third installation consisted of a title from an unpublished Jatra theater script, inscribed on an antique mirror placed in the front of the historic Diamond Library, famous for its Jatra theater scripts. The final intervention consisted of text in the Devanagiri script excerpted from a Doha by the poet saint Kabir and fitted onto the sides of a cycle van.

Each installation consisted of an ordinary, utilitarian object commonly seen in the area, made extraordinary by the addition of text and inserted into the everyday landscape of the streets of Chitpur.

With Hamdasti, I was also involved in establishing pedagogical processes that reflect the journey of our collective from the locality it is situated in to the opening up of dialogue and discussions in other cultural centers of the city through exhibitions, presentations, and discussions between the residents of Chitpur, artists, and visitors.

The beauty of this journey has been in the expansion of my detached vision as flaneur and artist to a more empathetic role as witness and collaborator.

To see more of Suhasini’s work, click here to check out our Visiting Art Fellows’ exhibit, Everyday Encounters, with the Harvard Ed Portal!

————–

☆ All opinions expressed by our interview subjects are their own and do not reflect the views of the Mittal Institute and its staff.