By Divya Saraf, MDS ’21

This past summer, with COVID-19 restrictions in place, I utilized the research grant awarded to me by the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute to investigate the postcolonial effects of the so-called “Company Painting” style, which was developed in the Indian subcontinent over the 18th and 19th centuries under the “patronage” of the British East India Company. The paintings were a result of British attempts to survey, record, and display Indian culture for British citizens, and the paintings have been instrumental in shaping public perceptions of India abroad. Indeed, even today, these paintings continue to be displayed in British and other national and private museum collections and all over the world — including the Harvard Art Museums’ collections.

Distinctive of these paintings is their “anthropological” aesthetic stylization. That is, these paintings endeavor to portray their subject-matter in a “natural” manner in order to persuade viewers that such subject-matter is neutral, scientific, and objective — merely documenting the customs, habits, and variety of India’s “native” peoples and cultures, as well as the diverse flora and fauna of the subcontinent. However, both this stylization and the continued curatorial practices and contexts in which these paintings are displayed are highly problematic.

Reorienting the Perspective

The stylization of these paintings was a blatant attempt on the part of British colonizers to efface the authorship and labor of the local artists who crafted the works, as well as to commodify and fetishize the peoples and practices endogenous to the Indian subcontinent. Still more problematic for our own historical moment, though, is the fact that this culture of effacement persists today in the ongoing curation of the paintings. Even now, the paintings are typically displayed in museums with no acknowledgement of their original authorship, let alone any historical or cultural contextualization provided by critical postcolonial, de-colonial, or subaltern scholarly discourses.

This failure (perhaps deliberate) on the part of institutions (primarily museums) to acknowledge these and other problematic dimensions of these paintings is especially surprising given the ascendency of post- and decolonial discourses within Western academic and scholarly institutions. Not only is there a wealth of post- and de-colonial theoretical discourses available to curators today — with major contributions by scholars such as Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Gurminder Bhambra, and Dipesh Chakrabarty — but, in fact, there exists significant art historical scholarship treating art and museums in the South Asian postcolonial context by scholars such as Saloni Mathur and Tapati Guha-Thakurta.

Perhaps one possible reason for the persistence of this cultural violence on the part of art institutions and curators stems from the fact that there seems to be little scholarship treating these Company Paintings from a specifically post- and/or de-colonial perspective. Given this gap in the scholarship and the correlative failure of institutions and curators to acknowledge such dimensions of these Company Paintings, the research I conducted this summer, and which I am now continuing as part of my Master in Design Studies thesis project at the GSD, attempts to fill this gap.

A Digital Investigation

While I had initially intended to conduct in-person research at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Library, and the Wallace Collection in London (all of which combined hold over 7,000 original Company Paintings), in light of global COVID-19 travel restrictions, my research focus and questions were instead re-articulated to address these issues as they manifest in the digital realm. What began as an investigation into curatorial practices that reinforce colonial narratives in British Company Paintings has been transformed into an investigation of the role that digital archives and collections play in shaping these narratives.

As institutions are increasingly being held responsible for their roles within hegemonic systems (both past and present), it becomes imperative to question not only the politics implicit in the narratives circulated by such institutions, but the methods and techniques by which the propagation and circulation of these narratives takes place. As such, my ongoing research aims to unmask the continued obscuration of the British Empire’s exploitation, exoticization, and subjugation of India’s peoples, specifically as it occurs in the digital curation of British Company Style paintings. Toward this end, my research efforts over this past summer went as follows.

Bridging the Gaps in Historical Archives

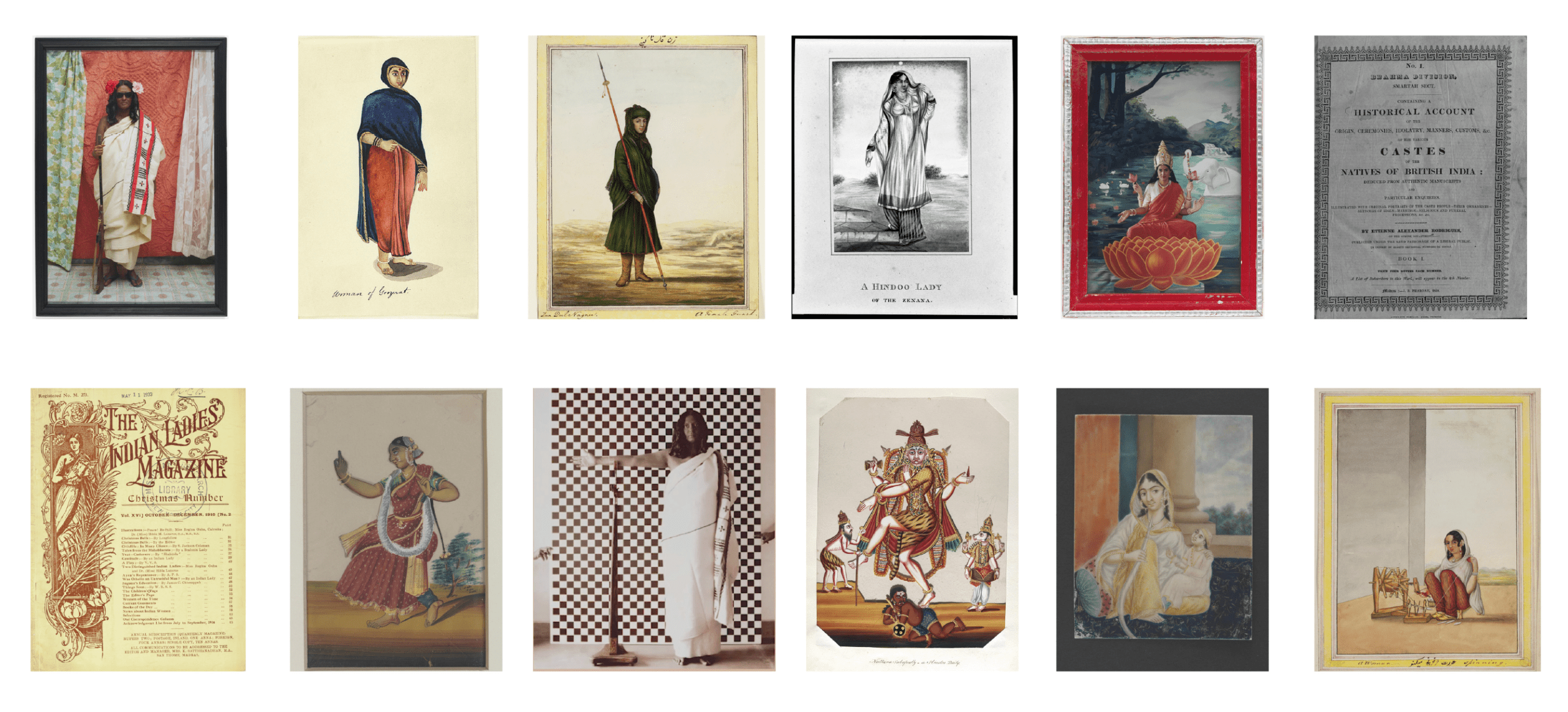

First, I carried out a series of close, critical examinations of the politics, ideologies, and histories implied and enforced by the narratives that curators have constructed when framing and contextualizing exhibitions and archival collections of Company paintings. This involved the study of exhibition descriptions, labels on specific artworks, and their provenance. Some of the exhibitions I looked at included the “Company School Painting in India (ca. 1770–1850)” exhibition in 2017 at The MET in New York, ongoing exhibitions in the Botanical Room at the Indian Museum in Kolkata, and the most recent exhibition at the Wallace Collection in London titled “Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company,” that only recently ended.

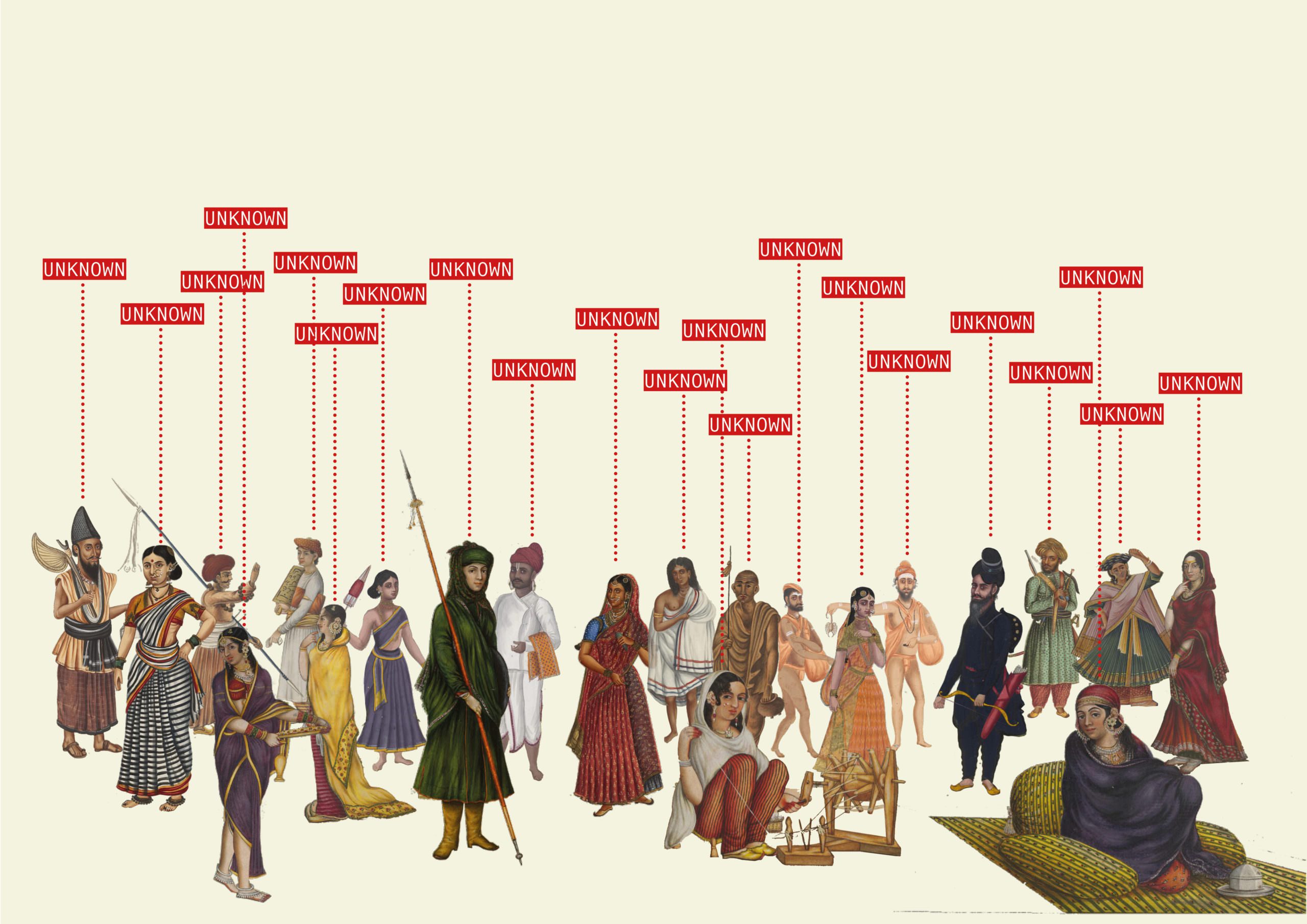

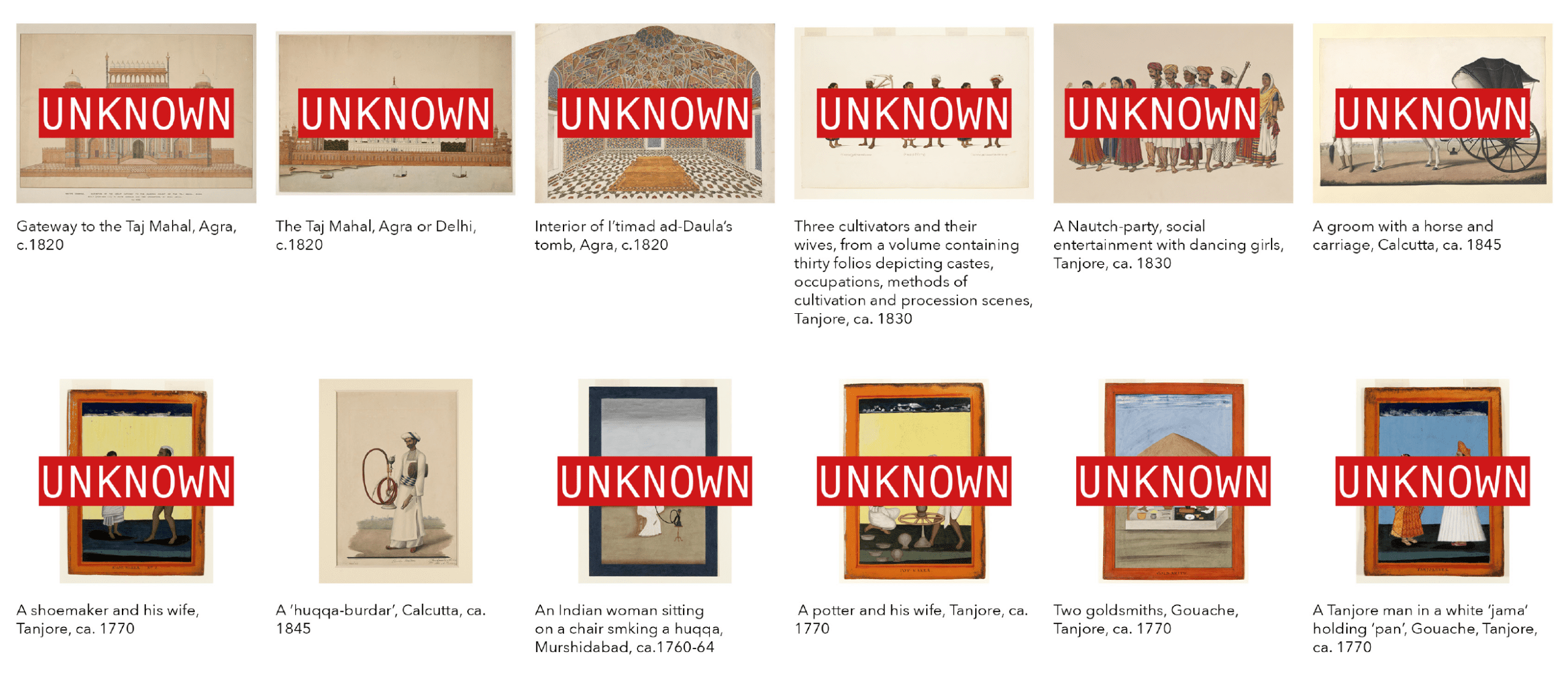

Secondly, I also looked at the kinds and amount of information available — and unavailable — to patrons about Company paintings, the history of display of these artworks, the movement of these artworks from the Indian subcontinent to locations abroad, and the reproduction of these artworks as prints and postcards. Perhaps the most telling detail I found was that, while there exists detailed information on the British commissioners and subsequent patrons of these works, the majority of the artists’ names are unknown, further revealing the importance of questioning the gaps in historical archives.

The third part of my research focused on methods of reorienting the Eurocentric narratives to include subaltern and postcolonial perspectives. This included introducing folios and surveys that the Company Paintings were initially part of, as a way of contextualizing the attempts to categorize Indian culture. By expanding the archive to include postcolonial scholarship and critical voices of contemporary artists from the South Asian diaspora, I attempt to insert missing subaltern narratives. I also experimented with modes of representation that highlight what might be missing from these collections in order to make visible the invisible.

Decolonizing the Narratives

As I carry this research forward into my thesis and beyond, I hope to further connect it to related questions present in our world today, such as: What role do digital archives play in perpetuating hegemonic colonial narratives? How can archives address the colonial narratives embedded within them? How can we begin to decolonize these narratives? How do we include critical, subaltern perspectives within these archives to expand and challenge the knowledge produced and reproduced in and through the digital realm? These are all issues which still demand further in-depth investigation, and ones I intend to continue to engage with through my work.

If our knowledge of the past is never direct and unmediated, but is instead an effect of far-reaching matrices of geo-culturally specific power relations, ongoing socio-political struggles, and deeply-rooted historical prejudices, then what is required is a denaturalization of our received historical narratives by means of a critical-historical interrogation of those narratives which today persist (perniciously) in preventing people from becoming what they are capable of creating themselves to be. So long as art functions as a means of revealing the diversity of human potentials to ourselves, it too must be subject to this form of critique.