A doctor administers the COVID-19 vaccine in Pakistan. Adobe Photo.

By Maha Rehman, Lahore University of Management Sciences

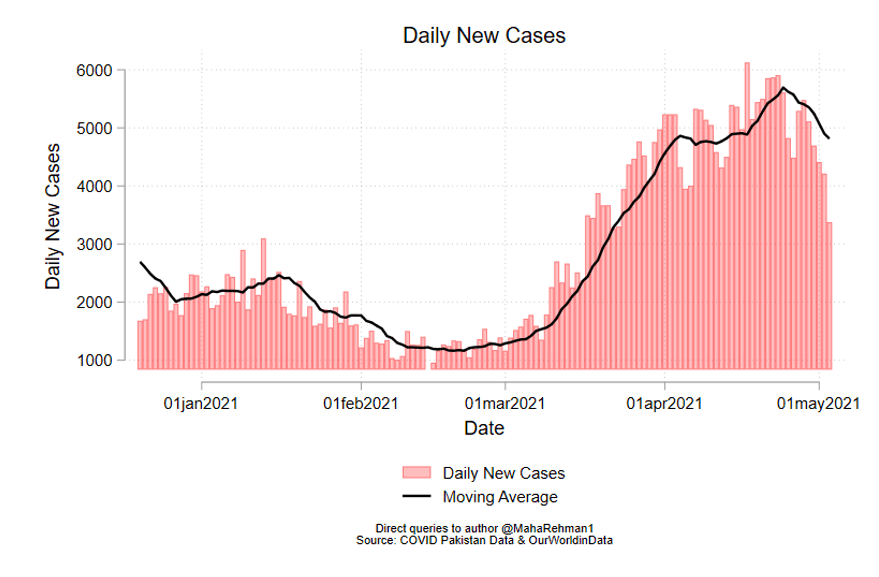

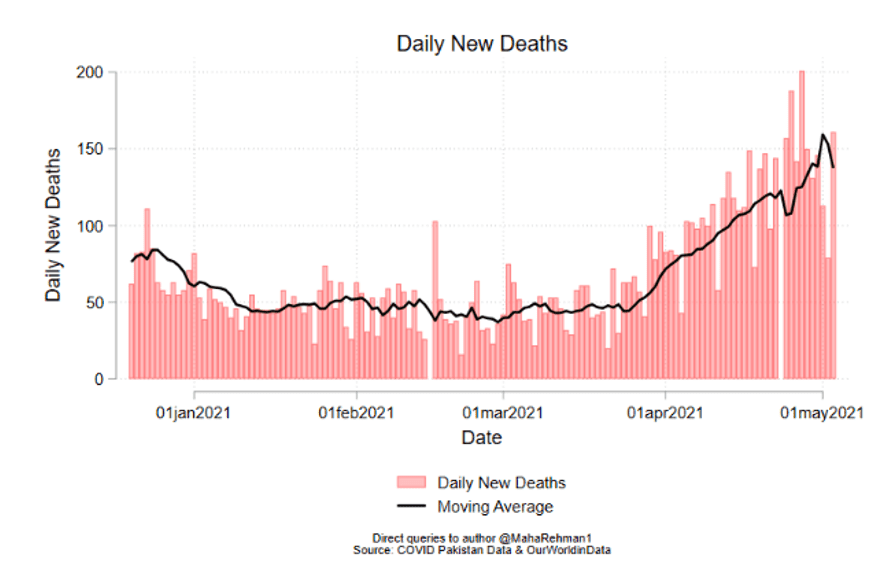

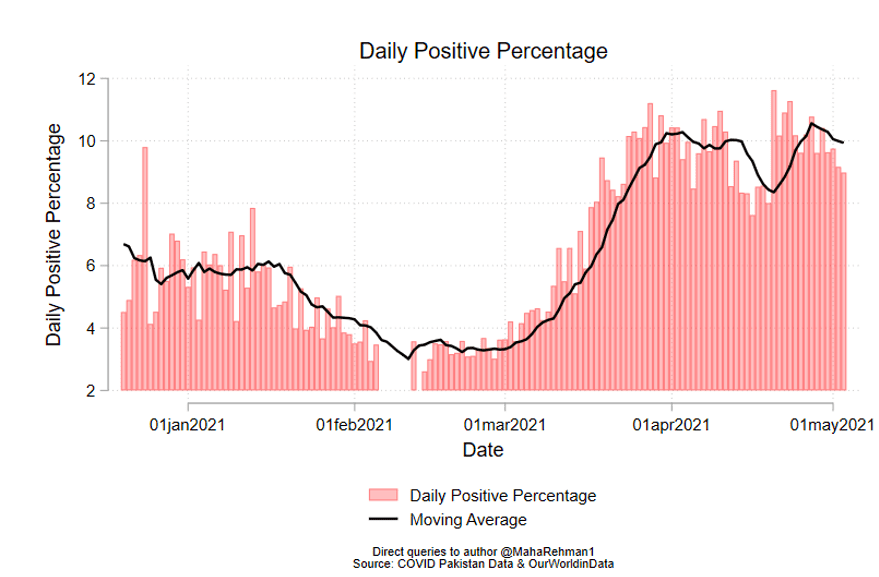

More than a year into the pandemic, Pakistan is fighting the third wave that is sweeping across its main urban centers. The hospitalization statistics increased manifold compared to the first and the second wave. However, after a relentless increase, the statistics are now beginning to register a slight respite. The seven-day moving average of the positive percentage now stands at 9.8%. Despite this trend, caution needs to reign supreme. By now we know all too well that these trends, while being exponential, are fragile. The sustained decrease is contingent on collective Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) compliance, among other factors. While we now understand some of these other factors well, many still remain elusive.

The national vaccination drive is also underway. With no local production, Pakistan has had to rely on purchasing the vaccine, donations or COVAX. As of May 5, 2021, Pakistan has vaccinated 2,967,870 citizens. This means 1.35 doses were administered per 100 citizens in the country. Aside from the fact that this supply has been constrained in developing countries, the rollout in Pakistan has seen challenges of its own.

Data provided by Maha Rehman, using data from “Our World in Data” and “Pakistan’s COVID Data.”

In light of these statistics, Pakistan’s policy response needs to have a multidimensional focus. Short-term policy measures must aim to stem the increase in numbers through effective SOP compliance and localized lockdowns as needed. Lahore’s district administration has been able to effectively turn the tide by vigilant monitoring and surveillance. Evidence from Bangladesh showcases the effectiveness of a four-component intervention to increasing mask wearing in local communities. The research team at Yale University, IPA and Stanford is working with regional partners to adapt the model for urban centers and scale implementation across South Asia. Similar evidence-driven measures must be deployed to increase compliance across the country.

Secondly, the vaccination drive needs to be ramped up to increase the percentage of vaccinated population. Global evidence is proof enough that this policy measure is not only critical in reducing hospitalization rates, but also in reducing transmission. In Pakistan, vaccine hesitancy should be systemically managed through effective communication strategies that increase trust in the vaccine and the vaccine provider. Effective communication campaigns have featured credible public health leaders, whose messages have been readily accepted and implemented by the people. We see one such example in India, where Nobel laureate economist Abhijit Banerjee led an effective communication campaign that increased compliance with SOPs. In other campaigns, credible local organizations have led successful campaigns. Peer advising at workplaces and in personal spheres have also yielded positive results to reduce vaccine hesitancy.

Finally, as the numbers decrease and the vaccinated population percentage increases, developing countries like Pakistan need to step up pandemic preparedness and resilience. Pakistan must build a robust health system that is sufficiently staffed; organize and implement agile data systems; and increase digital connectivity across the country, to tackle any future pandemic that challenges humanity.

Maha Rehman, a data analytics specialist, has almost a decade of experience in designing and executing evidence-based programs, products and policies to improve service delivery and impact. She is an Analytics Specialist and Adjunct Faculty at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) and Director Policy at the Mahbub ul Haq Research Centre, LUMS.