One of India’s most well-known architects reflects on 30 years of writing the city

Rahul Mehrotra. Photo: Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Rahul Mehrotra—practicing architect, urban designer, and educator—believes that “Society invests in us as architects and as urban designers to imagine better spatial possibilities that can enhance life,” and he has devoted his career to contributing to the urban landscape of India and beyond. Rahul, an LMSAI Steering Committee cabinet member, is the John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), where he is also Chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design; Director of the Master of Architecture in Urban Design Degree Program; and Co-Director of the Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design Degree Program.

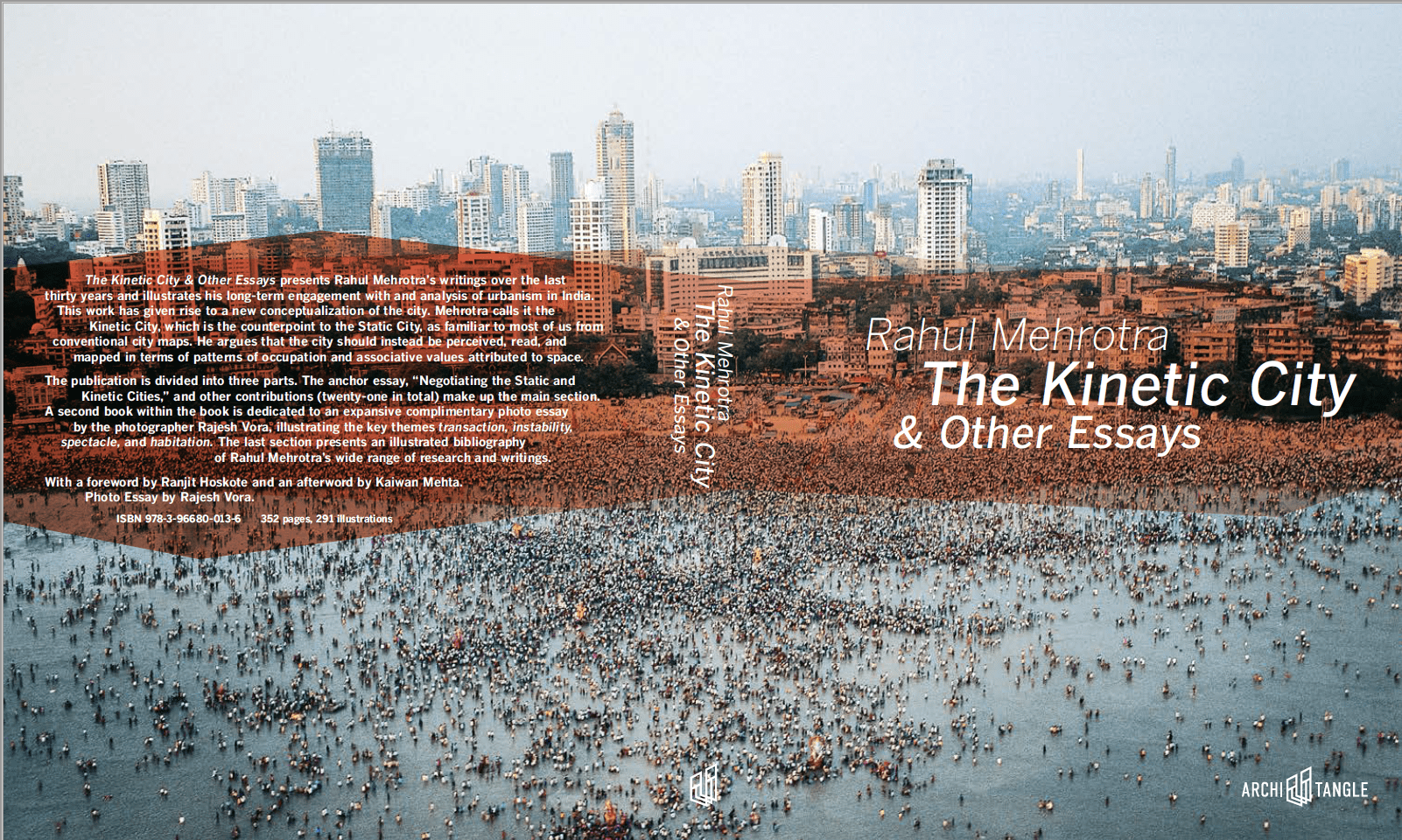

Mehrotra, founder of Mumbai + Boston based RMA Architects, recently released a new book, entitled The Kinetic City & Other Essays. The book presents Mehrotra’s writings over the last thirty years and illustrates his long-term engagement with and analysis of urbanism in India. This work has given rise to a new conceptualization of the city. Mehrotra calls it the Kinetic City, which is the counterpoint to the Static City, as familiar to most of us from conventional city maps. He argues that the city should instead be perceived, read, and mapped in terms of patterns of occupation and associative values attributed to space.

The Mittal Institute sat down with Mehrotra to learn more about his latest book, and the motivations behind it.

The Kinetic City & Other Essays by Rahul Mehrotra.

Mittal Institute: Rahul, congratulations on the new book, The Kinetic City & Other Essays. Would you like to start by giving us an overview of the book, the volume, and what people can expect from it?

Rahul Mehrotra: The book is a curated collection of essays which had been written over 30 years. What compelled me to put these together is that as I was reading the essays, I realized that over these three decades, my own interests have changed a lot, but so have the kinds of issues that are important for the city. And I realized that even if it wasn’t my intention, together, they form a good barometer on some issues connected with urban design and urban planning related to Bombay/Mumbai, as well as India more broadly – and some of these issues perhaps also resonate more globally.

The book is broadly broken into three parts: one is a collection of 21 essays over 30 years. The second is a photo essay by Rajesh Vora, who is a friend and who’s been working with me to capture aspects of Bombay’s particular urban condition for 30 years. And then the third part is a much smaller section, which is a visually annotated bibliography of all the books, catalogs, and brochures I have been part of the effort to produce. Many of these are on Bombay or Mumbai, but they also focus on architecture and urbanism more broadly.

Photo Credit: Rajesh Vora.

The other reason I did this book is to complement my book that preceded this one, Working in Mumbai, which was released about a year ago and was a 30-year reflection on the practice of architecture that I have been engaged with through my firm RMA Architects. I had not written about our practice or about our architecture before, so it was a reflection on three decades of work, but also how the city nourished the practice. In writing that book, I realized that the writings I did on Mumbai were also important for the practice. They were important in the way it maybe gave me presence in the city of Mumbai, but more importantly, it was a way that I was learning from the city. And so Working in Mumbai, was really about trying to discern what was the impact of the city and urban life on the architecture we were making. So, I thought a book like this, which captures 30 years of writing would be a good complement for the Working in Mumbai book, which is more project specific.

And these were both pandemic projects! I guess I was very productive in the pandemic, because I had a lot more time to reflect about these things and relook at my own writings during this period where we were all physically isolated.

Mittal Institute: What did you realize about your own thinking about the city and architecture over time?

Rahul Mehrotra: If I look at the 21 essays and the way they get more expansive in terms of the issues they are grappling with over time, what I see is the evolution of my own thinking about the city or of what I was seeing in the city shifting from a purely architectural gaze.

As time went on, I could see a shift in my own thinking to broader issues, whether it’s the impact of the pandemic or the ephemeral and the temporal and what the notion of time means in planning. I think what’s also interesting is that during the first 12 or 15 years of my career, I was practicing while being based solely in Mumbai, and my practice was very much based on reading architecture or understanding the physical form of the city. I was beginning to become uncomfortable with this reading and there was a tension in my own mind between the relationship between the hard and the soft city.

I think teaching was very important, because that exposed me and challenged me to expand those ideas to resonate more broadly for my students, but also to think about things more theoretically. And the pivotal point in that series of writings was an essay that I did called, “Negotiating the Static and the Kinetic City – the emergent urbanism of Mumbai,” where I began to argue that one can’t only look at the static city, but the presence of human beings in space makes visible another kind of softer city where architecture is often not the central spectacle of the city and one perhaps can’t even use architecture as the only instrument to imagine or to structure a city.

And that evolved into the idea of the “kinetic city,” which I began to then write about and theorize about as a kind of alternate reading beyond what one sees in representations of maps and two-dimensional articulation or even three-dimensional articulation of the city through urban and architectural form. And that’s where the title of the book comes from.

I began to argue that one can’t only look at the static city, but the presence of human beings in space makes visible another kind of softer city where architecture is often not the central spectacle of the city and one perhaps can’t even use architecture as the only instrument to imagine or to structure a city.

Mittal Institute: How do you see the idea of the kinetic city transforming our way of seeing cities in India and beyond?

One could begin to break away from being limited by the binaries that we use to organize and understand the world around us. We are often paralyzed by these binaries and can’t go beyond these critical descriptions to the propositional – which is often about blurring binaries to make solutions that reconcile the different forces that produce polarization and then the binaries to describe these conditions.

The other is to ask ourselves if we are making permanent solutions for temporary problems in the way we instrumentalize expensive and resource-intensive architecture to make cities. On a pragmatic level, if you take the farmers’ markets that happen in the United States, that’s an example of the kinetic city in operation. When you look at Mumbai, 90% of the city is made and remade in this fashion on a temporal scale.

And so, I think it really means that when we plan cities and when we govern cities that we should make space for landscapes in flux that rotate and occupy space differently at different times of the day, month, and year. We should make space multi-use. We should think about buildings with life cycles. We should sometimes design buildings knowing that they’re going to be reversed in 20 years. Look at the fact that in America there are over 2,000 abandoned malls that are just lying empty across the country, including the parking that surrounds them. What a wasteful use of resources.

I think it really means that when we plan cities and when we govern cities that we should make space for landscapes in flux that rotate and occupy space differently at different times of the day, month, and year. We should make space multi-use. We should think about buildings with life cycles. We should sometimes design buildings knowing that they’re going to be reversed in 20 years.

Mittal Institute: What did you learn, or what surprised you when you put together 30 years of writing?

Rahul Mehrotra: What really surprised me the most was that unknowingly one had created an archive on the city. In a sense, it was like capturing a trace or trail that was disappearing, and I think in the process of recovering that trail, one was just surprised by the extent I had focused on the historical architecture of Mumbai in the beginning of my career. And now I seem to be more obsessed with understanding the mega scale of the territory and its dynamics and their effect on the city and vice versa. I suppose as we grow, our spheres of concern broaden. I think I was very surprised by how much my sphere had grown.

Mittal Institute: What kinds of policy implications does this idea of the kinetic city have?

Rahul Mehrotra: It has huge policy implications that have to do with adding dimensions in terms of how we imagine use and, therefore, how we zone cities. How we attribute what’s legitimate in the city. How we even describe what we might call the “formal city.” In the same way, as we reserve space for X, Y and Z, including social institutions like hospitals and schools, we should be reserving spaces for ephemeral activities. We should be reserving spaces for unanticipated uses or for multiple uses. I think what we refer to as informal vendors or informal housing should become part of the formal imagination of the city. Why are they always illegitimate and contested and therefore susceptible to eviction and all the uncertainty that surrounds the lives of the most vulnerable?

Photo Credit: Rajesh Vora.

Mittal Institute: In reflecting on these cities that you have worked on for so long, what gives you hope? What keeps you going, even through all the challenges that cities like Mumbai present?

Rahul Mehrotra: Many things. The Indian architect Charles Correa said something beautiful, he said, “Bombay or Mumbai is a great city, but a terrible place.” That statement says it all! Mumbai has the energy, it has inherently in it hope, and it has people who work against all odds to make beautiful lives for themselves. And so, of course, for us as architects, our only hope and drive should be to make it a better place.

Society invests in us as architects and as urban designers to imagine better spatial possibilities that can enhance life, and Mumbai presents us the greatest challenge to do that, because it is a great city. Mumbai is also a great laboratory to learn from – an extreme condition where you see problems in their most complicated forms, and that’s why I look at these issues with my students at Harvard, hoping that we collectively learn from Mumbai – the Kinetic City!