Curvy roads of the silk trading route between China and India | Adobe photo by Mitrarudra.

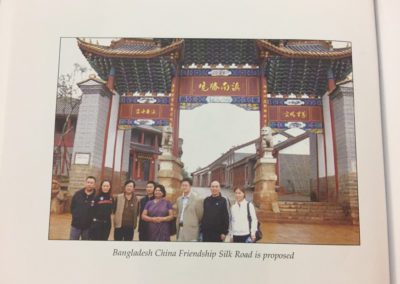

The Silk Road – an ancient network of international trade routes home to diverse culture and traditions – has long been the subject of interest for LMSAI Affiliate Hasna Moudud. Over the past several years, she has journeyed on and researched the Silk Road’s connections to South Asia. In an upcoming Mittal Institute seminar, Winds of Change: The Silk Road to South Asia, on Wednesday, November 17 at 10:00am (register here), Hasna will present findings from years of excursions and studies on the Southern Silk Road and the need to preserve this important part of the region’s heritage. The talk is hosted by Sugata Bose, Gardiner Professor of Oceanic History and Affairs, Harvard University.

The Mittal Institute has interviewed Hasna on past occasions about her travels and curated some of those fascinating pieces along with some of Hasna’s favorite photos from her time on this ancient trading route. Join her next week to learn more about the Silk Road’s lasting impact on commerce, culture and history.

80425

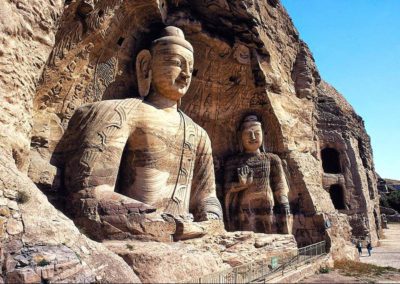

The Mogao Caves are a system of 492 temples 25 km southeast of the center of Dunhuang in Gansu province, China

photo 1

Tea Horse Road Museum, along the the Tea and Horse Road – an extensive network of routes connecting the important tea-growing regions in Yunnan and Sichuan with the Tibetan highlands

How did you first become interested in studying the Silk Road and Buddhism?

The Silk Road is a road from the past that connected people through trade — both in open material and secret spiritual goods. In translating 1,000-year-old Buddhist mystic poems, I discovered how the poems traveled from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan to Tibet and Mongolia through the Silk Road. The poems are lost now but preserved far away. Art, books, and secret tantric teachings traveled the Silk Road through secret passages in the Himalayas.

My interest in poetry grew through my father who was a great poet. We lived near the Kamlapur Buddhist monastery. After my long-awaited visit to Tibet, I learned how people from far away revered Atisha. However, besides the Buddhist priests, people in his birth country, Bangladesh, did not know about Atisha. I see myself as his daughter — and I am devoted to introducing Atisha Dionakara Srigana to his people in Bangladesh.

There is something poetic about your physical journey to discover the lost connections between Mongolia, India, and Bangladesh. I noticed that you also have published on poetry. Could you describe the role of poetry in the way that you conduct your research?

I sometimes call myself a writer and a poet, who loves nature. My research is about restoring and conserving the world’s lost and natural heritage. It is exciting to imagine how these Silk Road riders rode off, some to make money and others not, with a great sense of necessity — an urge to be a part of a race into the unknown — an urge shared with animals. It is a call of nature, just as the mountain and the sea often call me. Poetry opens roads to unusual places.

What has been the most surprising part of your research?

Sometimes information comes as a revelation and I do not have to research; it appears — like a piece of a poem. Additionally, as a masters student of old English literature, translation, and manuscript reading, I have a self-acquired specialization on handling old manuscripts, bringing in new meanings and focusing on the world of their period.

Can you describe the historical importance of the Silk Road and the geographies that it passed through? What was exchanged on the Silk Road?

Long before the “Silk Road” was named, silk roads and marine silk roads existed as the earliest highways to carry out trade, winding through developed urban cities and vast spans of desert and inhospitable terrain and requiring travel through extreme weather.

A main commodity was silk from China, but more items were added as valuable trading items. It was also a give-and-take of non-material kinds, including ideas, innovation, and religion. It was a battle to move forward with new ideas and ideologies and replace or readjust the old. Through it, true globalization took place. More and more excavations in recent times show how that map and its timeframe were constantly changing. History is being rewritten every day.

In your research visits along the Silk Road, what were the highlights of your experience? What did you learn in person that you may not have learned through research of texts?

I have the mind of a poet, an adventurer, and a romantic time traveler. In the winter of 1978, I traveled to China, flying over the Himalayas while wearing a silk sari and sipping tea. I imagined how it must have been to travel through these mountain passes to reach for the other side, looking for a spiritual and material market of goods. Ever since, I have visited various parts of the Silk Road, including Tibet and Xian, the beginning of the Chinese Silk Road. As I visited Dunguang at the end of Gobi Desert, I felt a thrill of what it may have been like thousands of years ago.

Those who traveled the Silk Road were not just traders, but adventurers, not knowing where they were heading. Once, I met a young man in a lonely run-down Silk Road station, who told me that he would like to take the journey like his forefathers did. Someone who looks at the stars at night and lets his mind flow to a faraway land and galaxy after galaxy. The mountain or the sea calls him. It is the call of the unknown, to conquer what is beyond, like it did to a young Alexander the Great.

I liked being in Mongolia and feeling a limitless horizon, which you cannot experience or imagine without being there. Or the ancient towns in China, as they were hundreds of years ago. Or Indian temples in Ajanta and Elliora; Buddhist monuments in Vishaka Pattanam in India; Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka; Mohashthangar, Wari Battedwar, or Moinamoti in Bangladesh. It is an endless list of names of places that result from human endeavor.

The Silk Road, to me, is a symbol of human yearning to be part of the greater world. The traveler is a true globalized citizen in an unknown world — unlike today’s globalized world, which can be reached quickly by plane, by internet, and by visual imagery. The ancient Silk Road was the road of imagination; it attracted a variety of people, from Sufis and scholars to thieves.

How has your research been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic? Have you adapted your research processes or faced any challenges in performing your research in this new capacity?

We have not been faced with a situation like this where the entire world has been simultaneously affected by the deadly coronavirus.

I was unable to give a seminar in June because COVID-19 had already spread throughout Asia and into other parts of the world, including the US. In fact, the pandemic has made me more aware of past pandemics that were attributed to the Silk Road, such the Plague, or Black Death, and smallpox. So, I have taken that into consideration and added it to the paper I am currently working on.

We are never really far away from catastrophes, whether they attack once in a hundred years or more frequently. Karma or cause and consequences have been responsible for human behaviors and acts toward the natural world. Human action is responsible for breaking down the balance between nature and humanity. But nothing prepared us for the current pandemic that has affected the entire world at once.

We in Asia are more exposed to disasters than people and policymakers in the US, whose lives are more predictable, while ours are not. Now, it is catching up, no matter how rich or developed you may be. It is a human tragedy we cannot blame on any one people or country — we are all in it. After COVID-19, the world will not be the same or as predictable as it was before.