A snowcapped peak in the Himalaya mountains. By Raimond Klavins.

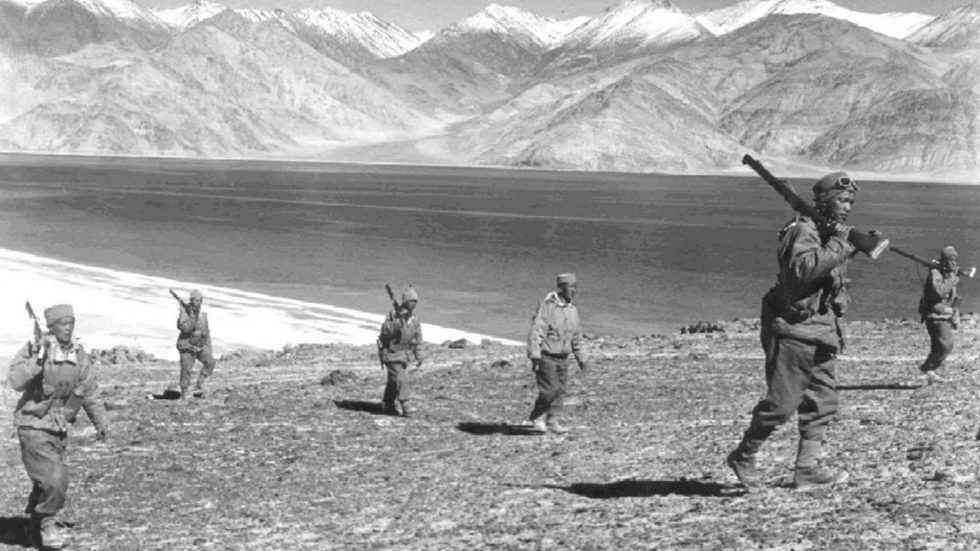

Amid the harsh, unforgiving terrain of the Himalayas, Chinese and Indian military troops fought for control of a disputed border during the Sino-Indian War of 1962. Attemps at diplomatic peace efforts dissolved in October; military action commenced soon after. The war saw large-scale hand-to-hand combat high in the mountains, at altitudes of 13,000 feet. Eventually, a cease-fire was proclaimed on November 20, 1962.

Nirupama Rao, a former Foreign Secretary of India, unknots this complex saga of the early years of the India-China relationship in her new book, The Fractured Himalaya. As a diplomat-practitioner, Rao’s telling is based not only on archival material from India, China, Britain and the United States, but also on a deep personal knowledge of China, where she served as India’s Ambassador. She shared her new book with the Mittal Institute ahead of her upcoming February 17 Borders in Modern Asia Seminar Series talk, “The Fractured Himalaya.” Join her at 12pm for her book talk, chaired by Professor Sugata Bose and co-sponsored by the Harvard University Asia Center, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, and Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute.

Mittal Institute: Nirupama, thank you so much for your time! In the introduction to The Fractured Himalaya, you dedicate it to the new generation, who have no personal memory of this time period. Can you tell us more about why you decided to write this book?

Nirupama Rao: This year, 2022, we mark 60 years after the momentous events of 1962, culminating in the brief, but bitter, conflict between India and China, fought in the high Himalaya, across terrain that is the most forbidding in the world. Public memory of the war is hazy and often incomplete, shot through with numerous stereotypes and insufficient ‘capture’ of what happened in that eventful year. A new generation of Indians, particularly millennials, have had no exposure to what happened in 1962. Given the current state of our relations with China, and all the attendant complications in that relationship, I felt that telling the story of the years between 1949 and 1962 in India-China ties, was necessary if a cogent, coherent perspective of the subject is to be formed in India’s public space today.

Nirupama Rao, former Foreign Secretary of India.

Mittal Institute: You have held a number of diplomatic positions, including India’s Ambassador to China, Peru, Bolivia, the United States, and High Commissioner for India to Sri Lanka. With all of your global experience, why did you decide to focus on China and India’s relationship in this book?

Nirupama Rao: In terms of my career as a diplomat, I began to work on China in the Indian foreign office way back in 1984, as a junior officer. Our relationship with that country was at the early period of normalization after the collapse of the early 1960’s. This professional involvement with China, and India’s relationship with that country, continued over significant phases in my career: first as desk officer, then as head of department for East Asian affairs in our foreign office, subsequently as India’s first (and only, so far) woman ambassador to China, and following that as Foreign Secretary (the senior-most officer and head of the Foreign Service) where I dealt closely with all our neighborhood relationships, particularly relations with China. Even outside my ambassadorship to China, I visited there frequently over the years, starting with 1986 (the early reform years) and then witnessing, on subsequent visits, the momentous changes transforming that country and also our bilateral relationship (including the ground-breaking visit of our then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi to China in 1988). I became an ‘expert’ on Sino-Indian boundary affairs, making field visits to many areas along our disputed border with China (popularly called the Line of Actual Control), and also visits to Tibet. This experience and background, and my being witness to (and often, participant in) the changes in the relationship, and my first-hand knowledge, as a diplomat-practitioner, of its complexities and intricacies, equipped me well, I believe, to write this book.

Mittal Institute: Can you share some of your insight into the war of 1962 – in summary, why do you surmise China and India went to war? Are there some overarching factors that led to the conflict?

Nirupama Rao: This was a war that need not have happened in the first place. India and China started off reasonably well at the start of the 1950s, as newly-established, independent countries, engaged in national consolidation, defining the need for peaceful coexistence between different national ideologies and systems of governance, stressing the need for a third force in global politics, beyond East-West divides that defined the Cold War. This history of Sino-Indian friendship during those years was short-lived because I believe, the two countries, particularly, India did not focus on the need to define and address the potential areas of difference that could lead to possible conflict. I particularly refer to the long land border between the two countries—one of the longest in the world—and also the whole question of Tibet, which is the region that abuts India almost all along this mountainous border (except for a stretch bordering Xinjiang). My book tells the story of how those differences came into the open because we neglected to address them comprehensively with a view to arriving at mutually acceptable solutions (particularly where our borders were concerned) that could make for a long-term and stable equilibrium in the relationship. Neighborhood relationships are, by their very nature, complex and sensitive; friendship is the outcome of a period where both sides work hard at settling differences. Friendship or even normalcy is never a ‘given;’ it is what you achieve after assessing the nature of the terrain, understanding the weak-spots that need attention and redressal, ensuring that outcomes are in tune with the national interest, in order to provide a satisfactory balance of interests between the two sides involved.

Rifle-toting Indian soldiers on patrol during the brief, bloody 1962 Sino-Indian border war. Wikipedia image.

Mittal Institute: Can you speak a bit about the impact of this conflict – how has it shaped China-India relations today?

Nirupama Rao: Perhaps less than in China, the conflict continues to impact the national consciousness in India as an event that amounted to a betrayal— by China of a friend—and a humiliation because of the military rout we suffered. But let us remember also that in more recent times both countries made a conscious, relatively fruitful effort over the last three to four decades to normalize their relations; resume dialogue on resolving differences on the border; stabilize the Line of Actual Control through the conclusion of a number of agreements to maintain peace and tranquility and build mutual confidence; and also expand relations particularly in trade and commerce, education, business, and people-to-people linkages. Unfortunately, both the structure and the process of this normalization was destroyed once the clash in the Galwan Valley in Ladakh between Indian and Chinese troops, took place in June 2020. Today, the situation in the border areas is tense and confrontational. We are dealing with a muscular and assertive China that is engaged in numerous transgressions across the Line of Actual Control, aggravating the risk of kinetic conflict that could have huge ramifications for our region.

Mittal Institute: And finally, to reflect on your 40-year career in public service, what are you most proud of as a diplomat?

Nirupama Rao: I am honored to have served my country as a public servant, and as the representative of a great democracy, as diplomat and Ambassador. As a woman officer, who ventured into areas of work that had not been traversed by my gender previously—as the first woman foreign office spokesperson of India, the first Indian woman to be high commissioner to Sri Lanka, and ambassador to China— fulfilling sensitive and complex assignments, I believe that my experience has served to motivate many young Indian women who aspire to careers in public service in India, particularly in our nation’s foreign service. The fact that my service to the nation has inspired and impacted countless young women is very meaningful for me, as I look back on my years as a diplomat.