By Nariman Aavani, Ph.D candidate in the Comparative Study of Religion at Harvard University, who studies Islamic and South Asian philosophical traditions

During this winter break, and thanks to a joint grant from Lakshmi Mittal South Asia Institute and the Asia Center, I had the unique opportunity to explore Hindu engagements with the Mathnawī of Rumī during the Mughal period in India. My goal in this trip was threefold: (a) to locate and acquire the manuscripts of Bhūpat Rāy’s Mathnawī, and the work of any other Hindu author who engaged with Rūmī’s Mathnawī; (b) to examine the content of Bhūpat’s Mathnawī and determine, albeit in a preliminary fashion, the ways he models his work after Rūmī’s work; and (c) to find the sources that Bhūpat Rāy (d. 1720) draws from in his work.

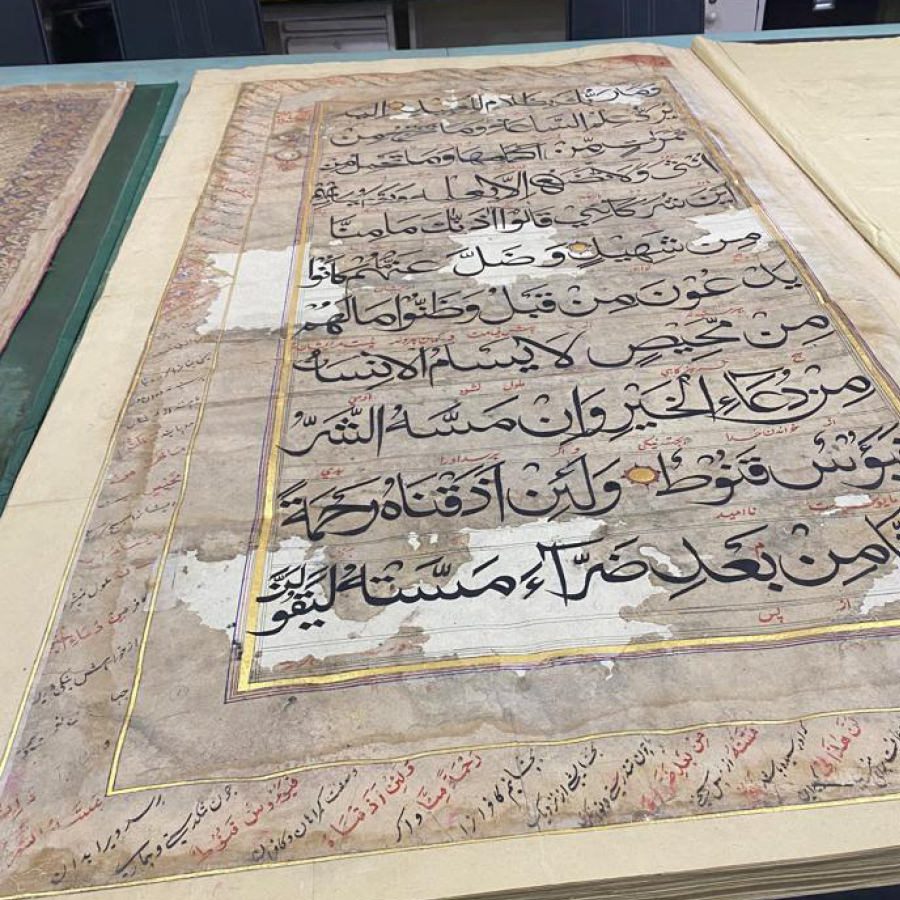

Prior to my departure, I had contacted three institutions in India to conduct archival research: the Noor Microfilm Center in New Delhi, Jammu and Kashmir Public Library in Srinagar Kashmir, and Khudabakhsh Library in Patna. I am glad to report that I was able to acquire digital copies of 11 manuscripts of two seminal texts: Banwālīdās Walīrām’s Mathnawī-yi shash wazn, and Bhūpat Rāy Bīgham’s Mathnawī both modeled after Rūmī’s Mathnawī.

Before examining the content of these works, it is necessary for me to say a few words about the reception of Rūmī’s Mathnawī in India to situate the works of our Hindu authors in the cultural context in which they were composed. Even prior to the Mughal period, India was a scene of literary presence of Rūmī’s work. In fact, one of the first instances of a work quoting verses from Rūmī was by an Indian author. Naṣīr al-Dīn Chirāgh Dehlī (d. 1356), the pupil and the successor of Niẓām al-Dīn Awliyā’ (d. 1328) refers to Mathnawī in his malfūẓāt. The first known commentary of the Mathnawī written by an Indian author is by Abū ’l-Ma‘ālī Lāhūrī (d.1615) a part of which Dārā Shukūḥ quotes in Sakīnat al-awliyā’. This work was followed by the commentaries of ‘Abd al-Laṭīf Gujrātī (d. 1638), Fatḥ-i Mathnawī of Fatḥ Muḥammad ‘Ayn al-‘Urafā’(d.1670), and Mukāshifāt-i raḍawī of Muḥammad Riḍā Multānī Lāhūrī (still active in 1700), to just name a few.

I mention these commentaries to show that Hindu engagement with Rūmī did not appear out of a vacuum and that these works should be understood in this context of intense literary activity centered on Rūmī in Mughal India.

Perhaps the first Hindu author who wrote a work imitating the mathnawī of Rūmī was Banwālīdās also known as Walīrām (d.1666). He was a munshi and a companion of Dārā Shukūh, the Mughal prince. He spent the final years of life in Kashmir, where he met the influential Sufi shaykh Mullā Shāh Badakhshī. Some sources even suggest that Mullā Shāh (d.1661) appointed Banwālīdās as his successor. This point led some sources to assume that he was a Muslim. However, in the introductory verses of his mathnawī he asserts explicitly that he is a Hindu:

نیست نقصانی چه شد گر هندوایم

زآنکه محو اصل یکتا هردوایم [1]

What is wrong if we are Hindus? There is no fault |

Since we both (i.e., Hindus and Muslims) are effaced in the Single Principle. || [2]

Banwālīdās’ mathnawī is often called the mathnawī-yi shahs wazn, meaning the mathnawī of six prosodic rhythms. As it is clear in the title itself, this work consists of six books, each of which possesses a unique rhythm. Based on my preliminary study of seven manuscripts of this text I acquired from libraries in Kashmir, what I found most intriguing about this work is the discrepancy among the manuscripts. Two out of the six chapters are different in some of the manuscripts. The discrepancy among the manuscripts was suggestive that Banwālīdās might not have composed these six chapters as a single work. However, there are verses in the text that suggest otherwise. For instance, in the first chapter, he writes:

درنگر اکنون بوجه یکدلی/ از سر تحقیق در نفس ولی

در لباس مولوی در گفت و گو/ مثنویها کرده شش دفتر خود او[3]

Now look at the soul of Walī with sympathy and out of a yearning for the truth.

He is talking in the guise of Rūmī, having himself composed mathnawīs in six chapters.

These verses indicate that Banwālīdās thinks of his Mathnawī as a work consisting of six chapters, the same number of chapters that the Mathnawī of Rūmī has. The last remark I would like to make before turning to Bhūpat Rāy’s Mathnawī concerns the readership of this work. Three out of seven manuscripts that I found start with the Muslim formula “basmalah” and the remaining four begin with the Hindu benedictory formula “shrī ganeshāy namā.”[4] This means that this work was popular in both Hindu and Muslim intellectual circles.

The second Hindu author, who engaged creatively with the Mathnawī of Rūmī, was Bhūpat Rāy Bīgham. He was born in Pathan Punjab and trained in Kashmir. Some sources suggest that he was a student of Mullā Shāh Badakhshī, the Sufi master with whom Prince Dārā Shukūh, Princess Jahānārā Begum, and Banwālīdās were associated, a fact which seems unlikely due to the age gap between the two.[5] His Hindu master was Narayan Cand, and his epithet ‘bairāgī’ might indicate that he had affiliations with Hindu monastic groups.

Bīgham’s Mathnawī, which consists of 44 tales, begins work with the following lines:

دل طپیدنها حکایت میکند/ چشم خونباران روایت میکند

تا زاصل خود جدا افتاده ام/ داد بیتابی چو بسمل داده ام[6]

The heart tells the tale of the heartbeats/ it narrates the story of eyes shedding tears of blood.

Ever since I became separated from the principle of the self, like a prey I have shouted my restlessness.

Bīgham describes how the heartbeats are telling us a tale. The tale of our separation from the source of ourselves, which has made us restless. What is most relevant for the purpose of my research was the striking similarity between these two verses and how Rūmī’s Mathnawī begins:

بشنو از نی چون حکایت میکند/ از جداییها شکایت میکند

کز نیستان تا مرا ببریدهاند/ از نفیرم مرد و زن نالیدهاند

Listen to the reed how it tells a tale (ḥakāyat)/ how it ccomplains from separation (judāyī). /

Ever since they cut me off from the reed-bed/ men and women have moaned in my lament.

Not only does Bīgham imitate Rūmī in expressing the idea of separation from the origin, but also the terminology he uses to express such concepts, including “tale” (ḥakāyat) and “separation” (judāyī) are taken directly from the Mathnawī of Rūmī. Moreover, there are other topics such as the importance of love (both divine and human) for the journey of self-discovery, along with a criticism of discursive thinking in which Bīgham is influenced by Rūmī’s Mathnawī.

The fact that Bīgham intentionally tries to imitate Rūmī might lead us to think that he lacks originality, but this view cannot be further from the truth. Bīgham is original at least in two ways: (a) he is original in including tales which have their origin in the local Indian culture. One can find many instances of this phenomenon in Bīgham’s work, including in the story of Dārā Shukūh and Bābā Lāl Dās, the tale of Śaṅkarācārya and the untouchable, the tale of Guru Nanak, the story of Arjuna in the Gita, and the story of a serpent charmer in Decan.

The second way Bīgham is quite original is in the way he translates Hindu concepts, such as meditation (dhyāna) and samādhi, in a language comprehensible to an ordinary Persian speaker. A prime example can be found in the story of Dārā Shukūh and Bābā Lāl Dās, in which Dārā Shukūh asks Bābā Lāl to explain the meaning of samādhi and dhyānā and Bīgham conveys their meaning through a tale about a hunter and a deer.

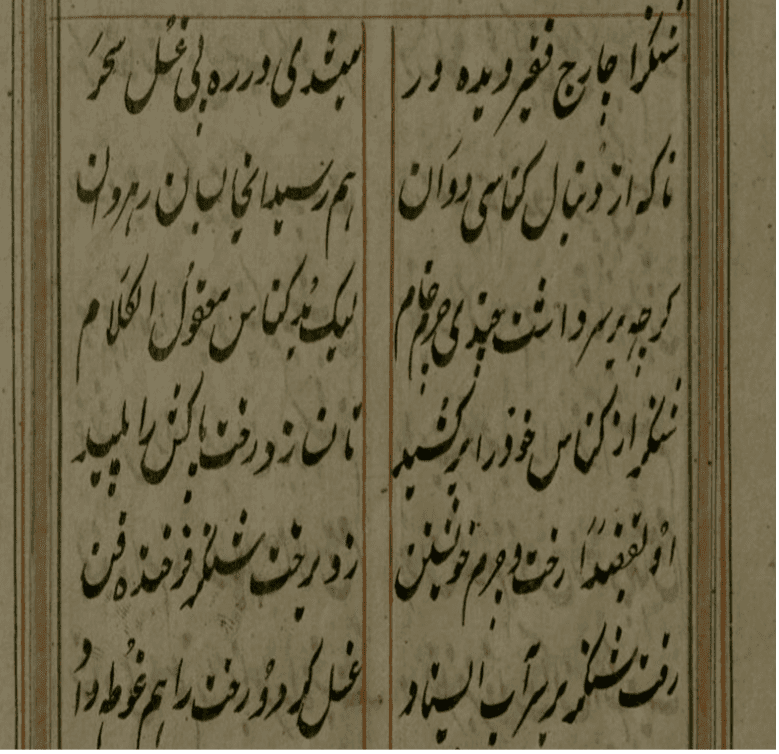

Nariman Aavani (left); The story of Śaṅkarācārya and the untouchable (caṇḍāla) in Bīgham’s Mathnawī, MS 2710 (right).

I would like to conclude by discussing an example of Hindu Sanskrit sources that Bīgham draws from in his Mathnawī. The 29th tale in Bīgham’s Mathnawī narrates the story of an encounter between Śaṅkarācārya, the great Hindu mystic, and an untouchable sweeper. This tale is based on one of the most famous works attributed to Śaṅkara, Manīṣāpañcakaṃ. As the tradition has it, Lord Shiva appears to Śaṅkara in the form of an untouchable (caṇḍāla). Śaṅkara had just bathed in the holy river and when he encounters the untouchable, he tried to avoid him, knowing that being in contact with an untouchable makes him impure. So, Śaṅkara commands the untouchable to go away. After hearing Śaṅkara’s words the untouchable says:

अन्नमयादन्नमयं अथवा चैतन्यमेव चैतन्यात्|

द्विजवर दूरीकर्तुं वाञ्चसि किं ब्रूहि गच्छ गच्छेति||

(Manīṣāpañcakaṃ, verse 1)

O the best of the twice born! what do you wish to send away by saying “go away! go away!”?

Do you want to send a body made of food away from [another] body made of food? Or do you want to send [one] consciousness away from [another] consciousness?

According to the Advaita tradition, the untouchable’s question is pointing towards a fundamental truth. There is ultimately one non-dual reality, which pervades all entities. This is the same conscious self that both Śaṅkara and the untouchable share. So, when Śańkara tells the untouchable to go away, he is mistaken, since the ultimate reality is a non-dual consciousness that pervades both Śaṅkara and the untouchable equally. Bīgham masterfully narrates this story in his Mathnawī:

شنکر از کناس خود را برکشید/ تا نسازد رخت پاکش را پلید

Shankara separated himself apart from the sweeper (kannās),

So that he [the sweeper] does not make his pure clothes impure.

It will be beyond the scope of this short report to provide a full account of the story in Bīgham’s Mathnawī. An important remaining question that I have is whether Bīgham took this story from Sanskrit sources or from versions of this story in sources in vernacular languages such as Hindavi. This is a question I hope to know more about during my ongoing research on the text. I would like to conclude by expressing my deep gratitude to the Lakshmi Mittal Institute and the Asia Center at Harvard once again for their generous grant and I hope that I will be able to participate in their programs and continue my relationship with the Institute in the years to come.

[1] MS 3342: fol. 45.

[2] All translations from Persian and Sanskrit are mine unless otherwise stated.

[3] MS 23: fol. 92.

[4] The Sanskrit form would be “śrīganeśāya namaḥ,” which means I pay obeisance to Ganesha.

[5] Bīgham died in 1720 and Mullā Shāh in 1661. For Bīgham to have studied with Mullā Shāh his year of birth should be no later than 1641 which seems rather unlikely given certain textual evidence in his other works.

[6] MS 7210: fol. 1.

[7] Below is the transcription of the entire story from MS 7512:

گفت بابا لال را داراشکوه/ کای توئی در استقامت همچو کوه

آنکه خوانندش تصور خاص و عام/ آنکه استغراق آمد در کلام

معنی این هردو آور در بیان/ سر پنهانیست بر من کن عیان

درجوابش گفت کای والا گهر/ نیست چونتو طالبی عالی نظر

دلکشی آمد تصور دربیان/ هست استغراق در تخلیص آن

گفت من چیزی نفهمیدم از این/ شرح این معنی کن ای اهل یقین

گفت شرح این سخن گویم کنون/ گوش نه بر حرف من ای ذوالفنون

آهویی را گر بدام آرد کسی/ آهو آندم میجهد از خود بسی

مینگیرد یک زمان آرام را/ میجهد تا بگسلد آن دام را

غیر جستن او نماند یک زمان/ گر نهی بر پای او بند گران

چون ببیند حال آهو صید گیر/ دانه اش را گم کند گردد حقیر

چون شود آهو حقیر و ناتوان/ باز مان از جهیدن بیگمان

روزگاری بگذرد چون این نمط/ آهو از جان بر نخیزد چون نقط

آن تصور هست پیش اهل دید/ معنی آن دلکشی آمد پدید

بعد از آبش اندک اندک آب و کاه/ میدهد صیاد صبح و شامگاه

بعد چندی چون شود الفت پذیر/ بند پایش بکسلد آن صید گیر

صید گیر از پیش آتش چون رود/ آهو از الفت بدنبالش رود

یکزمان بی صیدگیر آرام نیست/ دیگرش حاجت به بند و دام نیست