The Phantom Plague: How Tuberculosis Shaped Tuberculosis Shaped History, a new book from author and health journalist Vidya Krishnan, explores the global spread of tuberculosis—particularly among the most vulnerable populations across the globe—and lessons to be learned from historical public health crises. Vidya is an Indian health-focused investigative journalist, who regularly writes for Foreign Policy, The Atlantic, The Caravan, and was previously the health editor for The Hindu.

On March 24, World Tuberculosis Day, join Vidya for a book talk on Phantom Plague with discussant Madhukar Pai, Canada Research Chair in Translational Epidemiology & Global Health and chair Richard Cash, Senior Lecturer on Global Health, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The Mittal Institute sat down with Vidya to learn more about her research and the upcoming event.

Mittal Institute: Thank you for speaking with us, Vidya, and congratulations on your new book. You are a health-focused investigative journalist – how did you get started in journalism and why did you decide to focus on health as your beat?

Vidya Krishnan: Thank you for having me over. Almost as soon as I understood that adults have to make a living and have to pick a profession at some point, I knew I wanted to be a journalist. I love telling stories – long, complicated, meandering stories. I believe this is because of my own long, complicated story.

I grew up in Bhopal, a small town in central India, a decade after the Bhopal gas “tragedy.” While it was called a “tragedy,” it was calculated injustice and remains one of the world’s worst industrial disasters. I tried nine different beats before landing on health as my bread and butter issue. My father worked with UNICEF, in post disaster Bhopal, and I grew up around conversations surrounding polio campaigns, mass vaccination drives, etc. In the newsroom, I drifted towards the beat, and have always covered it from a social justice aspect. This is because I saw the aftermath of half the city I grew up in being gassed in their sleep and it’s inter-generational impact on health. That story is foundational to the kind of reporting I do.

Vidya Krishnan is a health-focused Indian investigative journalist and author.

Mittal Institute: Can you talk to us about the origins of this book – why did you focus on the spread of tuberculosis? What can readers draw from the book?

Vidya Krishnan: I did not intend to focus on tuberculosis or even write a book. This book forced itself on me, almost – with some help from my friends who insisted I write about TB so I would stop talking about TB. So, there isn’t a great origin story. I just had a book full of stories and was working in a media environment that did not want to publish bad news.

The book now belongs to the reader. I can’t tell them what to draw from it, but there are two things that I advocate: one, the right to health is a global conversation. I constantly draw the parallels between history and the present as well as the East and the West to emphasize that. And two: medicines cannot be governed, legally, the same was as refrigerators and cellphones. Globally, healthcare is becoming a luxury instead of being a right conferred by the state, and I talk a lot about intellectual property laws after setting up the story in the first half of the book. They are unjust laws that disproportionately impact black and brown nations.

Mittal Institute: Tuberculosis was largely controlled and cured in the West in the early 1900s. Can you talk to us about TB in South Asia today?

Vidya Krishnan: South Asia is the most crowded part of the world and is uniquely vulnerable to infectious diseases. South Africa and India are also the nations with the highest TB burden in the world. This is a preventable, curable infectious disease, but it is spreading in black and brown nations because medicines are too expensive.

As COVID-19 has already taught us, pathogens that emerge in Asia or Africa don’t remain contained there. The book attempts to force a conversation about the stigma and racial discrimination involved in treating infectious diseases. At its root, this is a solvable problem, but we only seem to treat people in black and brown nations when it is “cost-effective” as against effective.

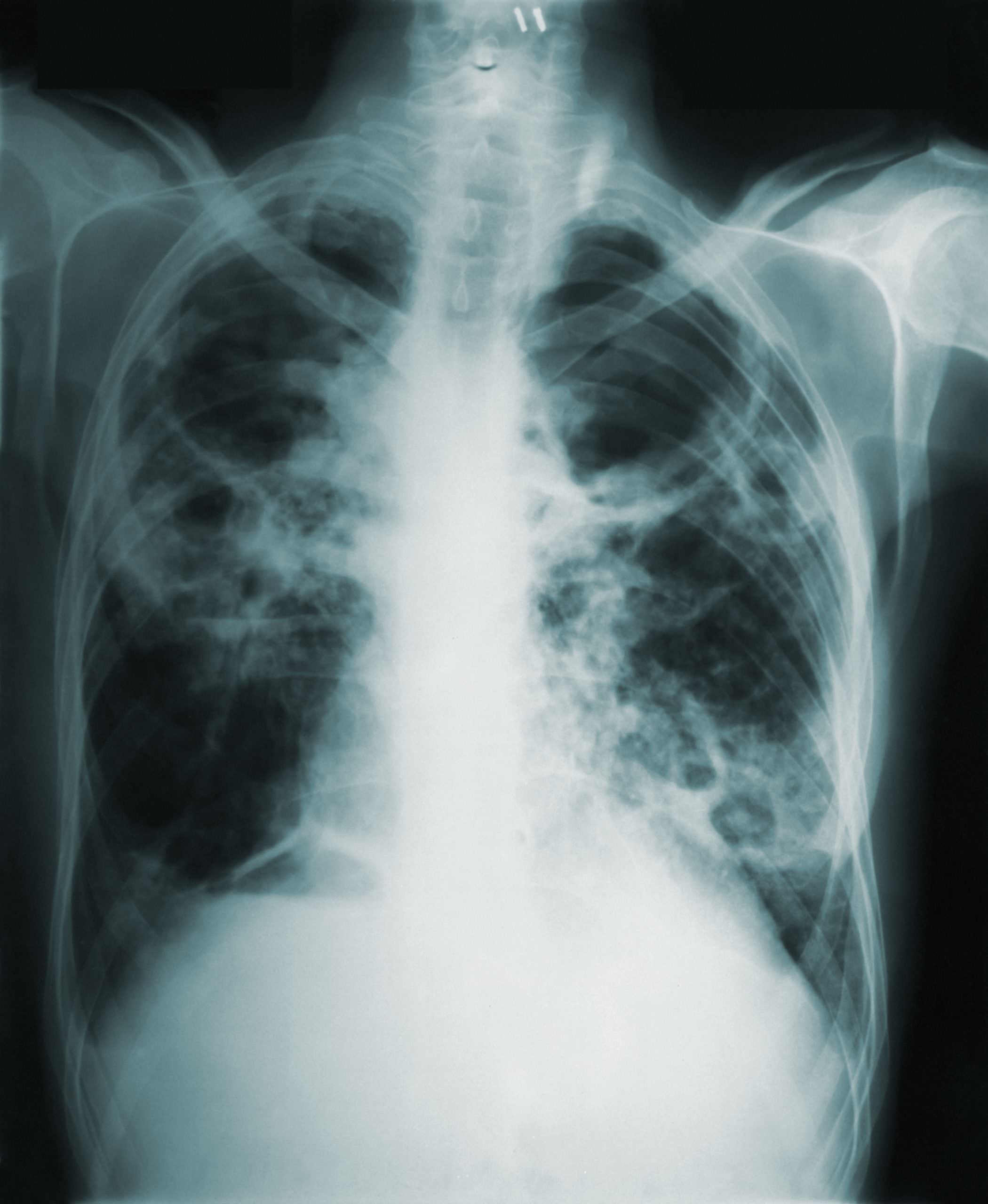

An x-ray shows pulmonary tuberculosis. By the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Drug-resistant, Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria, the pathogen responsible for causing the disease tuberculosis (TB). By the CDC.

Mittal Institute: In your mind, what measures could have been taken to eradicate tuberculosis in developing countries?

Vidya Krishnan: For starters, I’d love for the book to be a starting point for the phasing out of toxic injectables. These are old drugs that wouldn’t get marketing approvals today. One in four patients go deaf because of these toxic medicines. The book profiles the work of Médecins Sans Frontières [Doctors Without Borders] as well as many patients who have survived drug-resistant tuberculosis and are now fighting to ensure that newer, safer drugs like Bedaquiline are made available to patients.

Secondly, protecting intellectual property of multinational corporations – as millions die – is making global health vulnerable. As coronavirus has shown, we protect pharmaceutical patents to allow companies to succeed; meanwhile, communities – mostly black and brown – fail. Eradicating TB, much like eradicating COVID or malaria, requires structural changes in the global health order, starting with intellectual property on new TB medicines. The global battle against TB, especially in India, cannot be won if newer therapies like Bedaquiline and Delamanid get rationed due to patent monopolies. Both drugs are locked in patent monopolies and currently rationed in India, and other black/brown nations with a high burden of TB. It is also why a country like India has to rely on old, toxic antibiotics that are making patients deaf – one in four patients go deaf when they are put on unsafe injectables.

Mittal Institute: Do you see any parallels between the handling of TB and the handling of other infectious viruses, like COVID?

Vidya Krishnan: Yes, of course. Both are respiratory diseases. Both are preventable and curable. Coronavirus has now been a preventable disease for nearly two years. There are now upwards of 14 vaccine candidates. And, not coincidentally, both are devastating black and brown communities across the world.

We are now in month 18 of Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) negotiations. It’s shocking that the global health tsars are mulling over legalities as people die. This book is not about TB. That’s just a case in point. It is about our refusal to care for people who don’t look like us. Medicines are unaffordable in America, same as they are in India, where most American pharmaceutical companies manufacture their drugs at a small fraction of the cost they charge. I draw that parallel – between India and the U.S. – to show how unsustainable this system has become. Disease after disease has shown us that global health, especially when it comes to infectious diseases, is a universal conversation. We need to decenter the conversation from what serves the companies to what serves worst-affected communities.

Mittal Institute: In doing your research for the book, did anything surprise you?

Vidya Krishnan: Yes. I was surprised, heartbroken really, that the Indian government refused a new therapy, Bedaquiline, to cure a teenager who was diagnosed with extensively drug-resistant TB. She failed five rounds of treatment before dying. Her family was wrecked – all of it happened with the permission of our courts. India is the pharmacy of the world. That we can’t any longer find it in our hearts to care for a teenager (and millions like her) was… difficult to reconcile. I was surprised it stayed with me long enough to turn her story into a book.

Mittal Institute: What is next for you professionally? How can our community follow your work?

Vidya Krishnan: I just finished a long investigation on India’s deadly second wave for Caravan magazine while working on the book. So, I hope what’s next is a long vacation. After that, I intend to continue writing stories that are at the intersection of race, medicine and social justice. ☆

————————

☆ All opinions expressed by our interview subjects are their own and do not reflect the views of the Mittal Institute and its staff.