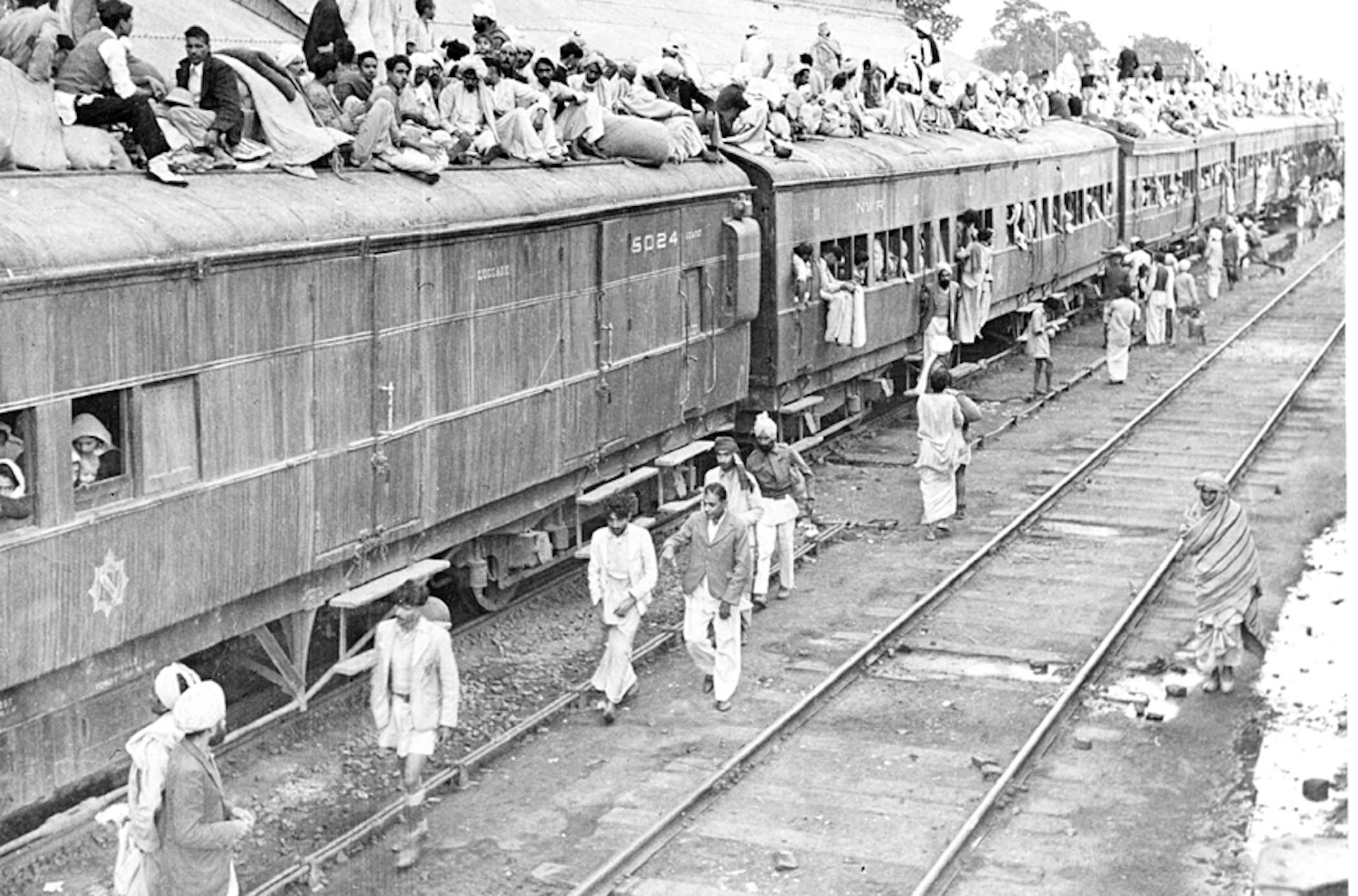

A Partition refugee special train at Ambala Station. The carriages are full and the refugees seek room on top. Wikipedia image.

An expert in public health and rights-based responses to humanitarian crises, Dr. Jennifer Leaning has spent her nearly 50-year career at the intersection of war and disaster, atrocities and conflict. Despite witnessing some of the darkest instances of human behavior, it is a ‘kindness of strangers’ motif that motivates her work. She applies this approach to the Mittal Institute’s 1947 Partition Project, which she has led since its inception in 2016.

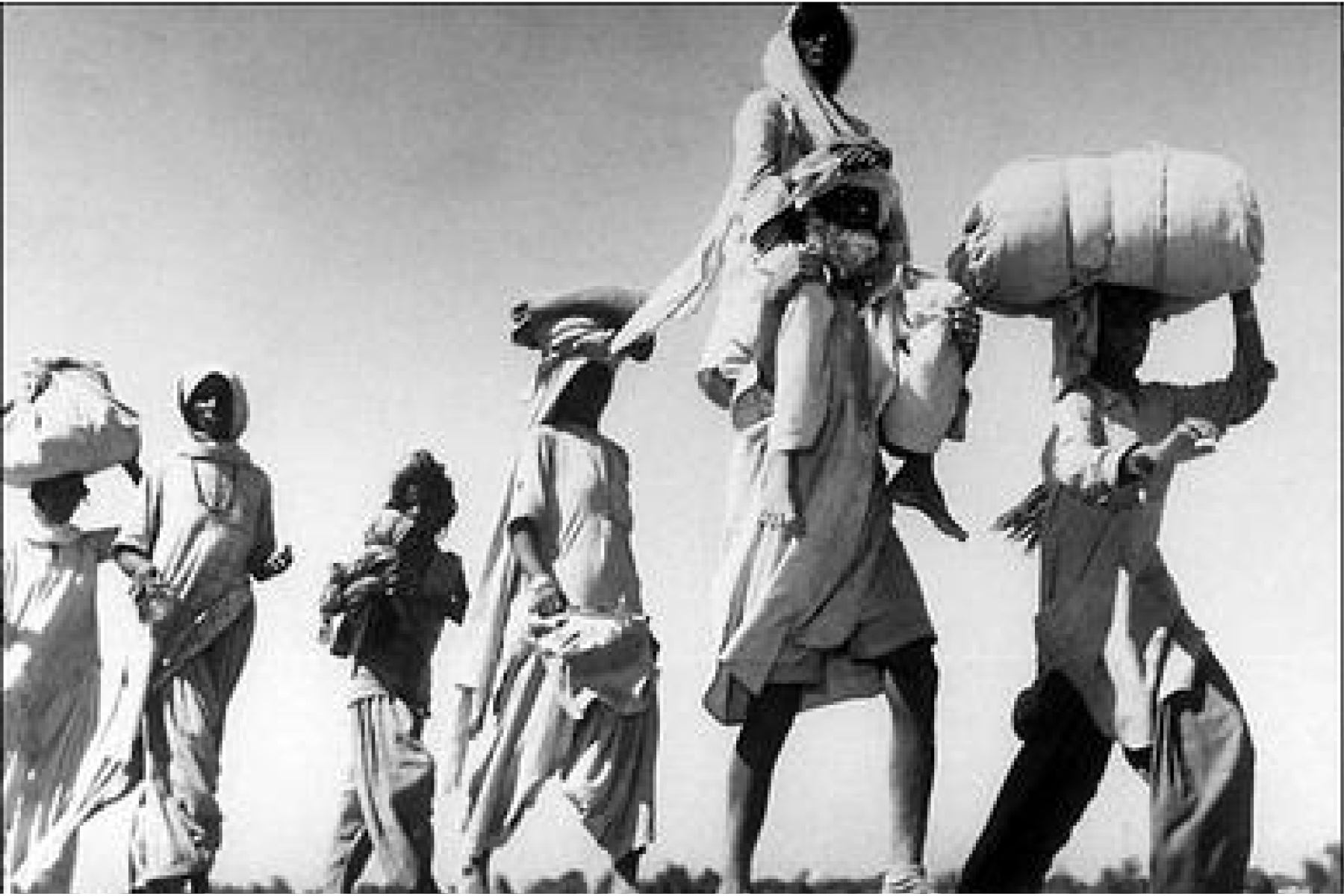

The Project studies the 1947 Partition of British India, termed the ‘greatest mass movement of humanity in history,’ following the end of a 300-year British rule. In an often violent upheaval, the population of the subcontinent was divided into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan, comprising West Pakistan and East Pakistan (which is now present-day Bangladesh). During the great episode of forced migration that ensued, millions of people fled their homes to find safety in areas across the new border, identified by religious affiliation. Many never made the journey because of sectarian attacks en route.

Yet in the midst of profound tragedy, Dr. Leaning notes the courage and compassion of the millions who were forced to move. “Partition is a deeply tragic episode in the birth story of these new nation states,” she explains, “and it is also a story of harried officials and charitable organizations who scrambled to respond and sustain the desperate millions who were in need.” To her, “this is what I would like those now living in the subcontinent to recognize about Partition.”

Dr. Jennifer Leaning. By Claudio Cambon.

Dr. Leaning, Senior Research Fellow at the Harvard FXB Center for Health and Human Rights and retired Professor of the Practice at Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health, will share her decades of Partition work in a new edited book, a collection of essays convened by the Mittal Institute with contributions from scholars in all three major affected countries in the subcontinent.

A ‘Complete Disruption’

Dr. Leaning was first struck by the Partition as an undergraduate at Radcliffe. It was there, and then as a Master’s student at the Harvard School of Public Health (and prior to earning her MD from the University of Chicago), that Dr. Leaning recalled reading a number of Partition accounts that caught her attention. “Such a large-scale migration of people who did not want to move – but were forced to – was already becoming a noticeable aspect of modern war,” she says. “It struck me as a really devastating aspect of the human condition.”

Her work on human rights and humanitarian response initially took her in a different direction. She worked clinically in emergency medicine; was the medical director of the Harvard Community Health Plan; and in 1997 founded the Program on Humanitarian Crises and Human Rights at the Harvard FXB Center. In 2000, she attended a Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies talk, and prompted by the discussion, broached the subject of Partition with the then-director, Professor Sudhir Anand. She asked him if he was aware of any studies on the numbers who had been forced to move and time scale over which this Partition migration had occurred. He said there were few recent studies, and they both agreed that these questions merited further study. The first step was to organize a seminar inviting scholars working on the demography of British India.

“At the first meeting, we talked about what was known and unknown in terms of the data; it turned out that there were many, many aspects that were not known and had not been explored,” Dr. Leaning explains. “We thought that the estimates of the numbers who had fled were low and there were no really solid numbers on those who had been killed. So we set out to pursue this.”

Dr. Leaning mobilized a small team, including Ken Hill, an esteemed demographer and professor at HSPH, and Sharon Stanton Russell, then a senior research scholar at the Center for International Studies at MIT. The first order of business was to decide to focus on the Punjab, which was known to have had a larger number of people cross borders in a shorter period of time than the Bengal side of the subcontinent (Partition-related migration along the Bengal border took place over a longer time period and the historical circumstances were different). The second move was to examine the excellent census records of British India and compare the undivided Punjab in 1941 against 1951, this time taking Punjab as again undivided and looking at both the Pakistani and Indian 1951 census reports and tables. This approach allowed for an exploration of who had moved and who was missing from the undivided Punjab in 1941 compared to the 1951 census. It was known historically that the bulk of the population of the Punjab had moved between 1947 and 1948.

A key boost to the analysis was finding that both the Indian and Pakistani census directors had agreed to ask one crucial additional question in the 1951 census—“where were you in 1947?” The team then extended their work to analyze the 1931 and 1971 census records and used techniques of indirect estimation to compare expected and actual noted births and deaths, by age and sex, across this 40-year record. The team found radically different and higher numbers of who had moved and who had died than in the then current estimates. Approximately 2-3 million people had died and 18 million had crossed the border, in either direction, from 1947-1951.

I knew enough about contemporary forced migration to recognize that these rates of deaths and migration were the largest that had ever been recorded. It still remains the largest ever recorded . . . It was clear that this period of time had been one of complete social disruption throughout the Punjab.

“I knew enough about contemporary forced migration to recognize that these rates of deaths and migration were the largest that had ever been recorded. It still remains the largest ever recorded,” says Dr. Leaning. “It was clear that this period of time had been one of complete social disruption throughout the Punjab.”

Together, they published a 2008 paper, “The Demographic Impact of Partition in the Punjab 1947,” in the Journal of Population Studies that provided the technical report of this research. “At the time, as a volunteer investigator with Physicians for Human Rights, I had been looking at forced migration in settings of war, where people were being hunted, such as in Somalia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Darfur…you had very high numbers because there was active hostile pursuit and killing,” says Dr. Leaning. “The Partition death rate that we had found was very high – and unless people are being actively chased and shot at and bombed and hunted, it does not approach the number of deaths that we witnessed and had been tracking in contemporary armed conflict. It was horrific how deadly Partition was compared to any experience of forced migration that I knew about.”

These sobering numbers spurred Dr. Leaning and the team to expand their work. They poured over Partition records in US libraries and the UK, especially in the British Library in London, as well as exploring library and archival sources in Delhi, India. They presented at conferences of the Population Association of America. They applied for grants from the Carnegie Foundation and the Weatherhead Center to support their research. And it was at that time that the Partition Project found a home at the Mittal Institute.

Left: A Sikh man carries his wife during their forced migration. Right: Rural Sikhs in a long oxcart train headed towards India. Wikipedia.

Humanizing the Data

In 2008, economists Prashant Bharadwaj, Asim Khwaja, and Atif Mian released their own Partition study, “The Big March: Migratory Flows after the Partition of India,” in Economic And Political Weekly. They were investigating economic parameters but they, too, examined the migration numbers using census comparisons – and came out with very similar findings as that of Dr. Leaning’s team.

“This really validated our numbers – that another team within a year had replicated what we found, through a completely different approach,” says Dr. Leaning. “So then for the next few years I began to acquire more and more information and decided that I would start to work on this book.”

Dr. Leaning herself began collaborating with the Mittal Institute in 2013, where she met Meena Hewett, former executive director, and Tarun Khanna, faculty director. Together, they explored transitioning the information-seeking phase to a new goal: putting a human face to the data. “I needed to understand much more of the social dynamics and what Partition meant to the people in India and Pakistan,” she explains. “Meena was the one who helped me recognize and shape this mission.”

After receiving a Mittal Institute grant for her work, Dr. Leaning set out to involve scholars from across the subcontinent in Partition research. With the help of Shubhangi Bhadada, a lawyer working at the Mittal Institute, they gathered scholars from Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, as well as from Harvard University—a first-of-its-kind project in which all three countries actively collaborated to document the demographic and humanitarian consequences of Partition. The project, officially titled, “Looking Back, Informing the Future: The 1947 Partition of British India,” and housed at the Mittal Institute, had a twofold aim: to build a network of scholars aligned on Partition research in the hopes of cultivating a rich, interdisciplinary exploration into one of the subcontinent’s most-defining events and to use techniques of crowdsourcing to capture memories: firsthand oral narratives from people in the subcontinent willing to recall the Partition history of themselves or their families.

The project on crowdsourcing memories was developed under the leadership of Tarun Khanna, Jorge Paulo Lemann Professor at Harvard Business School, and Karim Lakhani, Charles E. Wilson Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and Founder and Co-Director of Laboratory for Innovation Science at Harvard. Most of the 2,300 narratives they collected over the course of two years (2017-2019) were captured by trained volunteers who sought to reach those not represented in earlier histories: women, minorities, and the poor.

“Through the survey questionnaires, which I helped develop, we were interested in modes and conditions of flight: what they carried and who they lost along the way,” explains Dr. Leaning. “We also aimed this crowdsourcing to reach the poor, because most of the people who were being memorialized in the current archived collections of interviews talked primarily about their life post-Partition, and most of those people were well-to-do.” Eventually, these narratives became one of the underpinnings of the Mittal Institute’s Partition Project, and contributed to the foundational essays that are found in the forthcoming book.

A History of Pain; A History of Healing

Asked about the Partition book – tentatively due out in Fall 2022 – Dr. Leaning says, “There’s always much more to learn, but what I’m hoping is that this book will spark a real interest and respect in the subcontinent about an episode of distress and death that has not been matched anywhere else in the world.” The book represents the voices of 19 scholars, each with their own reflection on Partition: how it affected the fabric of the region’s politics, demographics and religion; how it has played out in art and architecture and urban design; how families told their stories and what the survivors now recall from those desperate days of flight and early resettlement.

It is paramount for Dr. Leaning that this book be readily available to the general public across South Asia. She and Bhadada are co-editors of the book, titled The 1947 Partition of British India: Forced Migration and Its Reverberations. The team is working with SAGE India Publishing to print and price the book so that people of modest means can purchase even one article. Digital access will also allow readers to download the book online for a nominal fee, and it will be available through outlets like Amazon. “This book will hopefully help substantiate a history of pain, which did not have very much basis except through the received stories from their families, or the sharing of these painful stories with other families close to them,” says Dr. Leaning. “I hope that it will resonate with people across the subcontinent and allow them to acknowledge the saga of survival and courage embedded in Partition, as well as the grief and loss.”

Dr. Leaning’s own chapter focuses on the six months leading up to Partition and the six months post, wherein she recounts the first months of the Indian and Pakistani governments’ efforts to navigate something totally unprecedented. Despite the virtual bedlam of those first months – millions on the roads and trains harassed by violent factional groups on both sides – there were also moments of humanity.

This is the ‘granddaddy’ of humanitarian response. There is a tradition of human concern that shaped the humanitarian response arising out of the Partition of British India that is unique in its shape, rooted by culture and traditions, but similar and in some ways more magnificent than many of the humanitarian responses we’ve now been able to muster.

“I want those in the humanitarian community to realize that this is the ‘granddaddy’ of humanitarian response,” she explains. “There is a tradition of human concern that shaped the humanitarian response arising out of the Partition of British India that is unique in its shape, rooted by culture and traditions, but similar and in some ways more magnificent than many of the humanitarian responses we’ve now been able to muster.”

The fate of two nations depended on the adept handling of this vast movement of people – and the weight of that responsibility was staggering. It brought out the ‘kindness of strangers’ as the subcontinent struggled to cope with the scale of misery and hate. “You had two governments behind the humanitarian response, and they all – the civil services, the military services, the bureaucrats, as well as the organized charities – did everything they could possibly do in their first two years of existence on both sides of that fraught border. And everything was mobilized towards easing the distress that their people experienced,” Dr. Leaning explains. “I’m quite surprised that these leaders didn’t crack and breakdown.”

For now, Dr. Leaning hopes that a ‘sense of humanity’ comes through in the book’s essays, which are sometimes deeply personal. “In most cases, people fought valiantly to help their family members but also strangers in need along the way. The basic story is survival through pain and suffering, hope in the midst of fear and the unknown. The volunteers and charitable groups tried so hard to help others,” she says. “Humanity will generally always come through. But often, as in Partition, with a great sense of loss.”

This article was written by Kellie Nault, Writer/Editor at the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute.