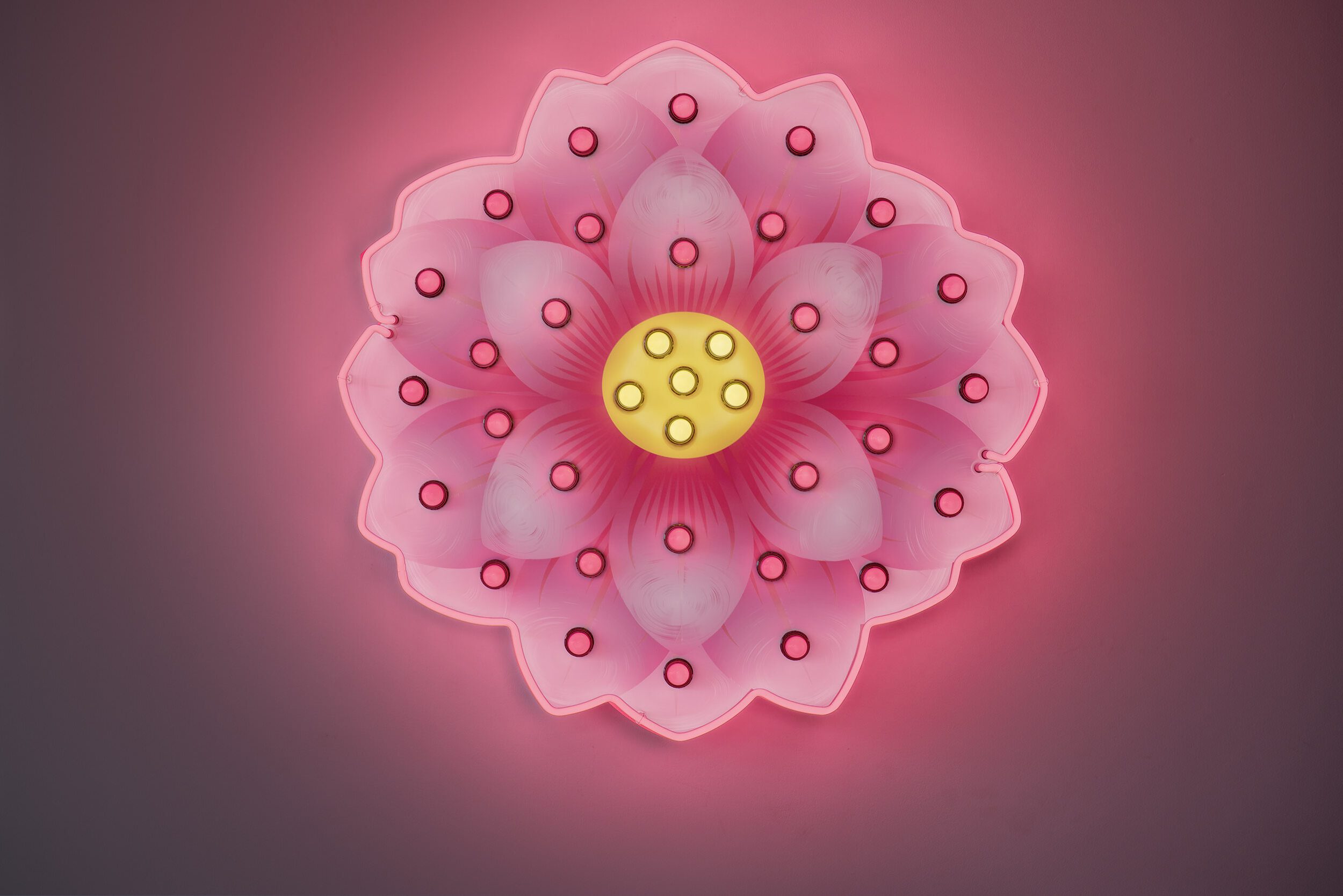

Padma – lotus [India], part of the Effloresence series by Professor Iftikhar Dadi and Elizabeth Dadi. Efflorescence denotes radiance, the blooming of a flower, and the flowering of civilization, but also bears negative valences such as discoloration. This doubled sense of the word provides an apt title for this series of large-scale illuminated sculptures of the national flowers of contested regions. Inspired by popular commercial signage, the works jump scale in their materiality and dimension: their industrial artifice acknowledges the manner in which delicate natural forms are deployed as fixed emblems to vindicate intangible claims of identity.

Iftikhar Dadi is the John H. Burris Professor in History of Art at Cornell University. He joins the Mittal Institute’s Annual Symposium for a discussion on Partition and the arts in a panel chaired by Jennifer Leaning, Professor of the Practice at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and faculty lead of the Mittal Institute’s Partition research, along with discussants Bhaskar Sarkar of UC Santa Barbara and Nadhra Khan of Lahore University of Management Sciences. LMSAI spoke with Professor Dadi about his work and art.

Mittal Institute: Professor Dadi, we look forward to your participation in our symposium. How did you first become interested in Partition? What are some examples of your work on this topic?

Iftikhar Dadi: My interest in the Partition is artistic and scholarly in the professional sense, of course; but above all, it is deeply personal. Both of my parents and much of their extended families hail from India and moved to Pakistan in the wake of Partition. My mother’s family, which was based in Lucknow and Bareilly, traces itself as members of the Rohillas, the quintessential middle-class professionals and civil servants that Aligarh Muslim University produced. On the other hand, my father’s immediate family was Gujarati-speaking and based in Bombay [now Mumbai]. The numerous members of the Gujarati-speaking community that had migrated to Karachi formed an elaborate labyrinth, and they were above all interested in trading and other business activities, rather than salaried employment. Members of both sides of my family have remained in India, and many others migrated to Pakistan and then to Canada, the U.S., Europe, and the Middle East, forming a dispersal that can no longer be gathered in any stable territory that is “home.”

Iftikhar Dadi, the John H. Burris Professor in History of Art at Cornell University.

My own artistic engagement with the legacy of the 1947 Partition began with a fortuitous meeting in 1996 at an exhibition in Copenhagen with Indian artist Nalini Malani, who had moved from Karachi to Bombay following the Partition. We discussed an alternative “celebration” of the 50th anniversary of the independence of India and Pakistan, as well as Partition, in 1997. This resulted in an exhibition titled, Mappings, which traveled to New Delhi, Bombay, and Lahore. And we collaborated to develop an artwork, Bloodlines, in 1997. But the work could not easily be made together—partly due to visa and travel restrictions—and its original and recent editions have therefore been fabricated by professional embroiderers in Karachi. Its exhibition in India in 2016 is an important milestone in my continued engagement with these tangled legacies.

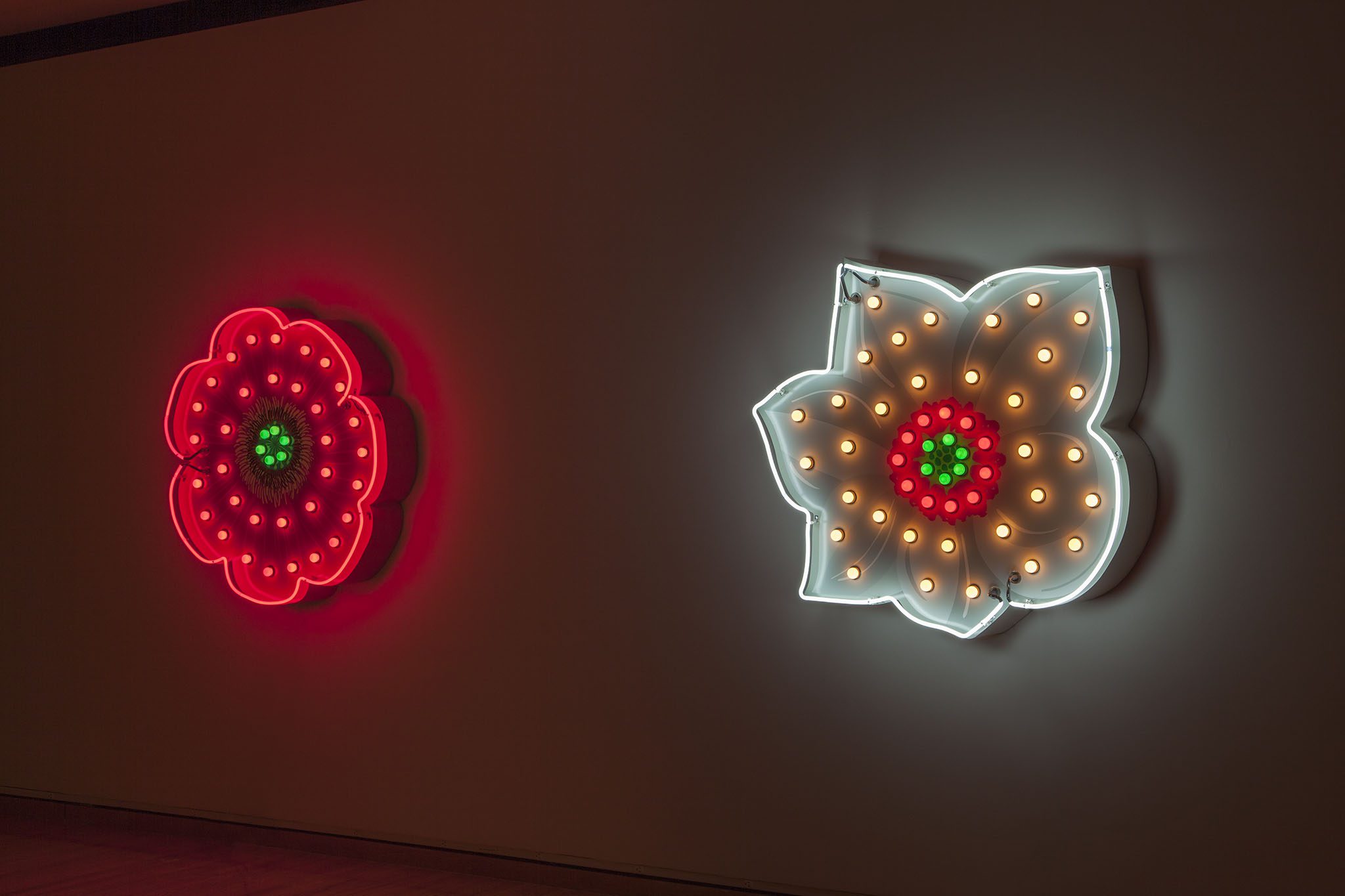

As an artist, I have collaborated with Elizabeth Dadi for over 20 years. Another body of work in which we address nationalism is the Efflorescence series (2013-ongoing). It uses the language of pop art and commercial signage in a large-scale commentary on sovereignty and the nation-state: the series consists of giant neon flowers that are industrially fabricated, each the national symbol of a country or region with disputed borders. In their giant scale and their graphic industrial character, the works confound expectations as to what delicate flowers should look like. The specific flowers referenced in this series are supposedly sacred national symbols, but grow widely, across nations and even across continents. The works speak to the arbitrariness of nationalism and its borders—their mesmerizing light and shape also evokes the lingering seductive power of nationalism on our imagination.

Installation at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge University (2019), as part of the exhibition Homelands: Art from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Laleh – tulip [Afghanistan] on left and Padma – lotus [India] on right.

Installation at John Hartell Gallery, Cornell University (2015).

Shaqa’iq an-numan – poppy [Palestine) on left and Mokran – magnolia [North Korea] on right.

Mittal Institute: Partition has long been captured via written text. Why is it crucial to also reflect on it from an art and architectural perspective?

Iftikhar Dadi: Modern nationalism in South Asia has largely succeeded in sustaining ethically repugnant notions of unwanted others in the national body politic. This nationalism works primarily at both the elite and the popular levels by foregrounding stereotypes and discouraging face-to-face encounters with the complex humanity of others. Despite this, the vital work of numerous writers, musicians, filmmakers, and artists continues to inspire others across borders and beyond narrow identitarian affiliations. The aesthetic dimension of life in South Asia is thus radically political, in the sense that it allows us to imaginatively and affectively participate in a universe where a constrained sense of belonging is positively challenged and one’s sense of being is invited to be enhanced in open-ended ways.

In the arena of contemporary art, this crucial work being performed by artists, curators, writers, galleries, and museums—whether located in South Asia or beyond—is therefore of immense significance. Art provides us and the successive generations with intellectual and affective resources for rethinking our stances, and these effects may address immediate conditions, or they may be latent, proleptic, or prophetic. From this perspective, it does not matter whether the art is accessible or difficult, how widely the work circulates, or what the specific identity of the artist is.

Contemporary practice by a growing number of South Asian artists—most of whom did not experience firsthand either 1947, or the 1971 liberation of Bangladesh—is now beginning to grapple with the latent complexity of Partition’s effects, which extends from grand nationalist, geopolitical and identitarian agendas into the most personal and intimate aspects of the self.

While a number of modernist artists who experienced the Partition, such as Satish Gujral and Tyeb Mehta, did respond to Partition’s effects in their work, others approached it only in metaphorical and indirect ways. However, contemporary practice by a growing number of South Asian artists—most of whom did not experience firsthand either 1947 or the 1971 liberation of Bangladesh—is now beginning to grapple with the latent complexity of Partition’s effects, which extends from grand nationalist, geopolitical, and identitarian agendas into the most personal and intimate aspects of the self.

The contemporary work of art offers no transcendence and no attempt to redeem events and crises into a utopian metaphor. Rather, it resolutely refuses all claims to authenticity and insistently maps the multiple dislocations and antinomies of the social field. It is characterized by its being both fully immersed in its time, yet also simultaneously out of joint with it, and therefore not bound by the “timeliness” of its demands or by the sense of “reasonably” addressing only what is politically and socially pragmatic. Much of contemporary art ethically critiques our conceptions and practices of modern institutions, such as the nation state, which were meant to usher us into an enlightened new age, but which can no longer suppress the violent memories of their founding or their inassimilable exclusions and remainders.

I am co-curating a major exhibition of pop art from South Asia and its diaspora at the Sharjah Art Foundation. This will run from September 2 through December 15, 2022. Sharjah is easy to get to if one flies through Dubai, so I hope many people will be able to view this show, which deploys play and humor to address serious questions.

Cinema is also an important form for reflecting on social divides and the role of the aesthetic in addressing it. My book Lahore Cinema: Between Realism and Fable is forthcoming later this year. It examines, among other questions, the Partition as a haunting in Lahore’s commercial cinema, and the cultural politics of language between East Pakistan and West Pakistan.

Mittal Institute: Your book, Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia, received a Book Prize from the American Institute of Pakistan Studies. It traces the emergence of modernism over the course of the 20th century through the work of selected South Asian artists. Can you describe the evolution of this book?

Iftikhar Dadi: I wrote this book keeping in mind a number of audiences: scholars of modernism who remain narrow in their scope and clearly need to understand it in a genuinely global context; researchers in South Asia area studies who ought to incorporate cultural and artists developments much more in their analyses; students of Islamic art who are perplexed when dealing with its encounter with modernity; and young artists from South Asia who do not understand their own history very well. Most of the artists I discuss are still largely unknown in the West, so part of the challenge has been to write in a manner that explicates their life and work without simplistic reduction.

At one level, this book is an intellectual history of the emergence of modernism in the art of Pakistan and South Asia during the 20th century. But I begin with arguing that terms such as “art” and “modernism” are far from simple, and do not have stable meanings. The book thus also forays into a number of theoretical and postcolonial concerns that have broader relevance for the study of modern art in much of the world.

One issue is that modern art still commonly refers to a rather narrow range of meaning and scope. It basically focuses on developments in Paris (Impressionism, etc.) in the 19th century and to selected Euro-American movements in the 20th century (Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, etc.). But if we understand modernity as a socially transformative condition that was in force across much of the world from the 19th century on, how are we to understand artistic practices that were associated with these momentous changes?

Another problem confronting the study of modernism is that of the universal versus the particular, which is mapped onto temporal change versus geographic particularity. Cubism, for example, is understood as a “universal” movement that decisively altered the trajectory of modernism. But if one begins to look at what happened in specific geographic areas, such as parts of Asia or Africa, the impulse so far has been to write delimited studies of “national” or regional art histories.

My book attempts to provide another narrative to these larger methodological questions. It views modernism as constituting a much larger set of practices in many sites through travel and exchange of people and ideas. This is a productive way out of the center-periphery issues that still characterize the study of modern art. I understand modernism as a global aesthetic. This is not so surprising if we see modernism as a search for aesthetic forms beyond what was available in Europe itself.

Finally, I argue that the tradition/modernity relation is far more complex than a simple binary in opposition. I understand “tradition” to be a complex assemblage of ideas and practices, and some of them provide paths for modernist exploration and development. Indeed, modernism cannot be fully understood unless its genealogy in “traditions” across the world is also accounted for.

Modern art in the region of South and West Asia and Africa therefore emerges via a complex negotiation with “tradition,” with a resonant and affirmative encounter with transnational modernism and with the need to situate itself in relation to colonial and postcolonial impasses and possibilities.

Modern art in the region of South and West Asia and Africa therefore emerges via a complex negotiation with “tradition,” with a resonant and affirmative encounter with transnational modernism and with the need to situate itself in relation to colonial and postcolonial impasses and possibilities. In many cases, in the absence of developed art-historical methodologies and concepts, artists developed their practice with reference to other modalities of “tradition,” such as oral and written literatures.

Investigating artistic practices at the peripheries of canonical modernism demands careful and patient work, including an awareness of social and political history, languages and literatures, and other cultural conceptions the artists engaged with—in short, a writing of artistic practice that respects the formalist properties of the art, but also situates it with reference to the intellectual history of the time and the region, and along the artists’ experiences of physical and metaphorical travel. I have tried to do justice to these issues in my book.

Mittal Institute: Your exhibitions have been shown across the globe. What exhibit are you most proud of and why?

Iftikhar Dadi: Our collaborative work (Iftikhar Dadi & Elizabeth Dadi) has been shown in numerous sites and exhibitions. Some of our work can be viewed at www.dadiart.net. It’s impossible to identify a single exhibition as being a favorite. Generally speaking, we welcome the opportunity for a sustained engagement with a site and the opportunity to make new work. We are invited to exhibit at the upcoming Sharjah Biennial opening February 2023, which will be a major art exhibition based on the vision of the renowned curator Okwui Enwezor (recently deceased) and which is being realized and expanded upon by Hoor Al Qasimi and an advisory team of scholars and curators. Our participation will consist of existing work and a new site-specific installation that we are presently working on.