Bandipur National Park wildfire in the Karnataka state in India. Wikipedia.

Wildfires cause a deterioration in air quality, loss of property, crops, resources, animals and people, according to the WHO. With rising temperatures, ecosystems are drying out, leading to an increase in the size and frequency of wildfires in some regions. In agriculture, fire is often used to remove crop waste after harvests, control weeds and pests or clear land. The resulting air pollution from fires, both wildfires and agricultural fires, has a variety of health issues attached to it.

Residents of South Asia know these impacts all too well, but so does Tina Liu, a Mittal Institute Graduate Student Associate and Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard. Growing up in southern California, Tina witnessed wildfires that burned through swaths of dry shrubs on the hills surrounding freeways and even witnessed firsthand the acrid smoke that emanated from these fires. Tina finds the increase in the intensity and size of wildfires–combined with their widespread impact over the past decade–particularly troubling. She has focused her research on this area in places such as India and Indonesia, using satellite data and atmospheric modeling to quantify the impacts of fires on air quality and public health. She recently published two papers with another in review on the topic of crop residue burning and the impact on air-quality degradation.

Tina Liu, Mittal Institute Graduate Student Associate, is a Ph.D candidate in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard.

Air Quality & Agricultural Fires: The Search for Answers

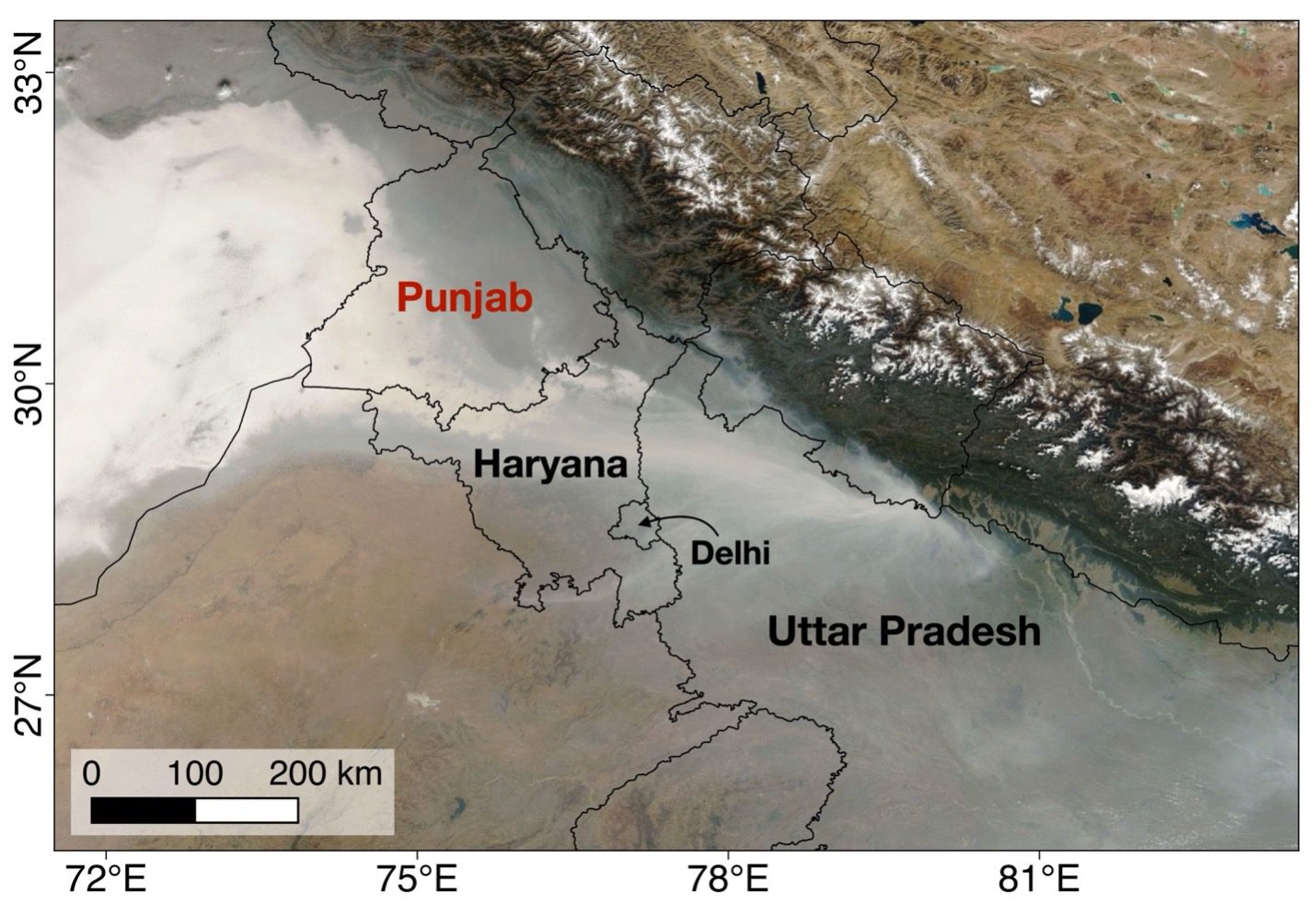

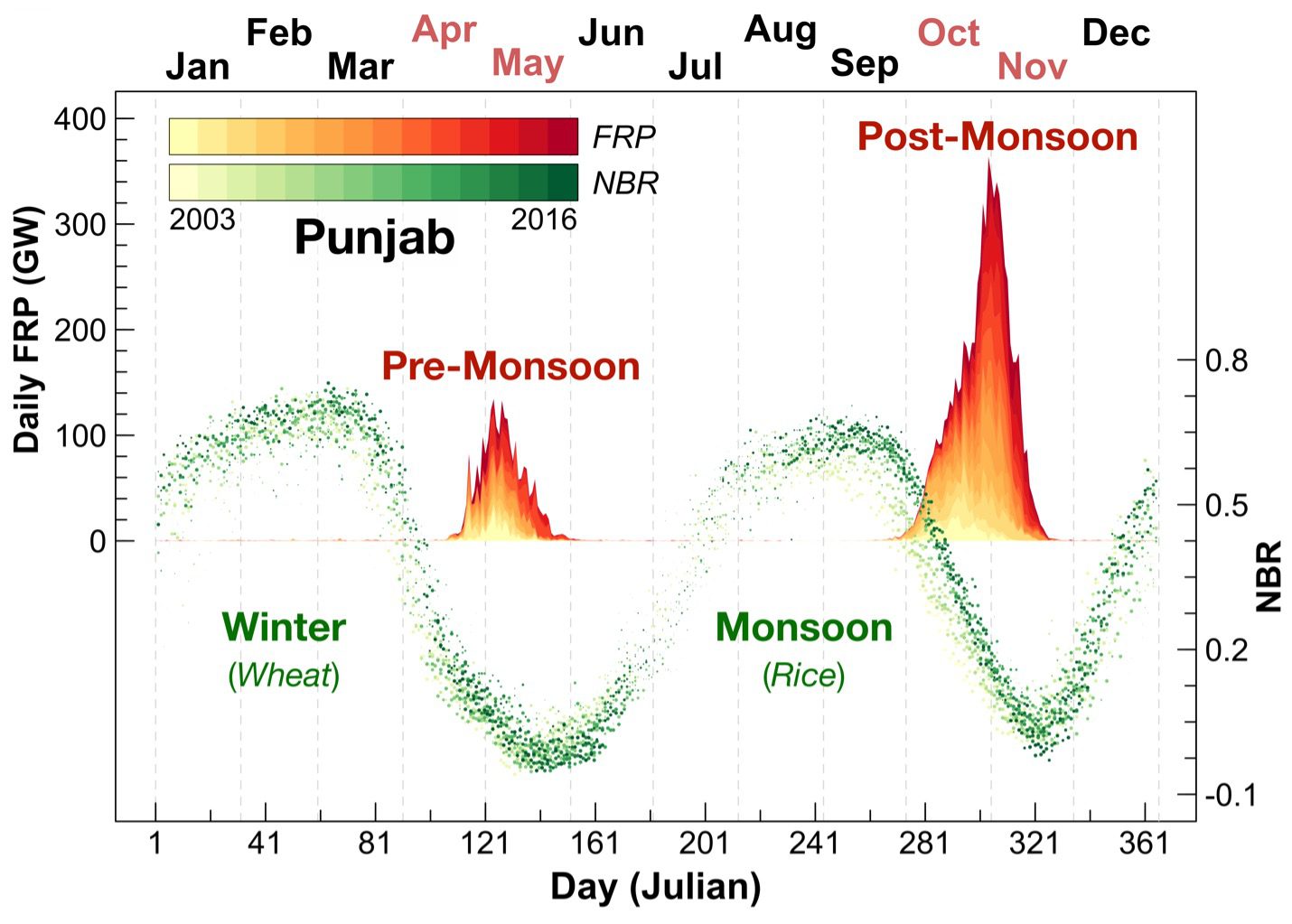

Tina’s research on the Indo-Gangetic Plain in India led to the discovery of the main potential drivers for air quality and the public health consequences of poor air quality in the region. Using satellite observations, Tina and her team found a two-week delay between the time that agricultural fires occurred in the state of Punjab during the post-monsoon period (October-November) from 2003 to 2016. After monsoon rice harvests, many farmers burn crop residues that remain on the field to quickly prepare for winter wheat planting, due to the short turnaround time from rice to wheat in the double-crop cycle. The findings were published in a recent paper, “Detection of delay in post-monsoon agricultural burning across Punjab, India: potential drivers and implications for air quality.”

Example of thick haze and fog over the Indo-Gangetic Plain (Liu et al., 2021). MODIS/Terra corrected reflectance image of thick haze and fog extending across northern India and Punjab, Pakistan on November 6, 2017 (NASA Worldview; https://worldview.earthdata.nasa.gov/).

The rise in mechanized harvesting since the 1980s also promotes crop-residue burning as a more tractable and cost-effective option, since the use of combine harvesters leaves behind short rice stalks that are difficult to manually remove from the field. Along with an increase in fire activity, the delay in post-monsoon fires may exacerbate air quality issues, particularly in dense population centers that are located downwind from the fires, such as New Delhi, and this in turn increases the likelihood of extreme air pollution episodes.

Along with an increase in fire activity, the delay in post-monsoon fires may exacerbate air quality issues, particularly in dense population centers that are located downwind from the fires, such as New Delhi, and this in turn increases the likelihood of extreme air pollution episodes.

As the season progresses from post-monsoon to winter, the prevailing meteorology yields poorer ventilation conditions that trap smoke near the surface and causes the increase in concentration of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), tiny suspended particles in the air with a diameter less than 2.5 micrometers. These particles can be lodged deep into the lungs, and public health studies have linked PM2.5 concentrations to higher risk of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases as well as premature death.

A recent groundwater policy in Punjab, the Preservation of Sub-Soil Water Act, 2009, may partly explain the delay in the post-monsoon fire season. Due to severe groundwater depletion, the act prohibits rice planting until after a certain date, so that the onset of the summer monsoon rains may supplement irrigation needs. Indeed, satellite data also shows a shift in the timing of the monsoon rice growing season. The unintended air quality consequences of the cascading delays from the monsoon growing season to post-monsoon fires leaves north India in a difficult position to find solutions that tackle two pressing issues, groundwater depletion and air quality.

A recent groundwater policy in Punjab, the Preservation of Sub-Soil Water Act, 2009, may partly explain the delay in the post-monsoon fire season. Due to severe groundwater depletion, the act prohibits rice planting until after a certain date, so that the onset of the summer monsoon rains may supplement irrigation needs.

Tina has published a subsequent paper “Crop residue burning practices across North India using household survey data: bridging gaps in satellite observations.”

Estimates of fire emissions, or the amount of greenhouse gases and aerosols fires emit, is uncertain for agricultural fires in North India. More accurate estimates are needed as input for atmospheric modeling to quantify the impact that fires have on air quality. The research aimed to understand how to constrain fire emissions and did so by combining satellite and household survey data. The research accounted for factors such as potentially missed satellite detections of fires, as agricultural fires are small and short-lasting compared to wildfires, and thick haze and smoke cover can obscure satellite sensors from ‘seeing’ the fires.

Tina’s third, and most recent paper is currently in review and titled, “Cascading delays in the monsoon rice growing season and post-monsoon agricultural fires likely exacerbate air pollution in north India.”

For this paper, Tina used an atmospheric model to quantify the effect that delays in the post-monsoon fire season have on air quality degradation. The atmospheric model uses a meteorological dataset, with parameters such as wind direction and speed, to calculate the transport of gases and aerosols.

Cycles of fire activity and vegetation greenness in Punjab, India (Liu et al., 2021). Fire Radiative Power (FRP) is a proxy for fire intensity, and the Normalized Burn Ratio is a proxy for greenness, or crop growth. Daily FRP (left axis) and median NBR (right axis) in Punjab. FRP values are stacked with earlier years on the bottom. The double-crop cycle indicated by NBR is predominantly a rice-wheat rotation, where high values correspond to crop growth and maturity and low values to the harvests and the transition period between crops. Pre-monsoon fires occur from April to May after the winter wheat growing season, and post-monsoon fires occur from October to November after the monsoon rice growing season. The fire intensity in the post-monsoon period is much higher than in the pre-monsoon.

The research team also conducted hypothetical experiments to measure the impact of the timing of the fire season on air quality degradation. The study found that air pollution is made worse for cities that are downwind and close in proximity to any fires, such as New Delhi. Findings also indicated that the delays in the fire season are linked to increases in fire activity – that is, farmers with a shorter turnaround time to transition between rice and wheat are more likely to burn crop residues – then the impact of the delays are even more severe.

All three papers answered a lingering question Tina had been asking since the days of her undergraduate research: Why is there a shift toward a later post-monsoon fire season in northwest India, and how much do these delays contribute to air pollution?

Tina’s research sheds light on what we can learn about human actions and decisions, either through state policies or through changes in the agricultural system. Her team was able to use household survey data to gain further information on when and how farmers set fires to supplement satellite data.

Tina’s research sheds light on what we can learn about human actions and decisions, either through state policies or through changes in the agricultural system. Her team was able to use household survey data to gain further information on when and how farmers set fires to supplement satellite data.

Although there are uncertainties, limits, and caveats to satellite observations, household survey data, and atmospheric modeling, it’s important to tackle air quality research with creative methods, such as integrating different sources of data or taking advantage of advances in cloud-based geospatial computing and data storage.

The Path Ahead

Tina recently completed her dissertation and will be working with UC Irvine’s Dr. James Randerson as a NOAA Climate & Global Change postdoctoral fellow. She will be working primarily on wildfires in the western United States, but also hopes to improve global agricultural fire emissions estimates in a future project.

She says that her time as a GSA at the Mittal Institute has been an enriching part of her research experience at Harvard, “I’ve enjoyed participating in GSA round tables both via Zoom and in person and learning about research topics in other fields. Since my research is interdisciplinary, it’s neat to see what GSAs are working on and glean some inspiration!” Among other positive experiences at Harvard that stand out are forging collaborations with other graduate students in mentoring undergraduates, receiving all-around moral and technical support from the Atmospheric Chemistry Modeling Group, and having the opportunity to present research in Jakarta, Indonesia and at meetings such as the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting and Google’s Earth Engine Summit.

This article was written by Taamra Segal, Mittal Institute Communications Manager in the New Delhi office.

Papers Referenced:

Liu, T., L.J. Mickley, R. Gautam, M.K. Singh, R.S. DeFries, and M.E. Marlier (2021). Detection of delay in post-monsoon agricultural burning across Punjab, India: potential drivers and consequences for air quality. Environ. Res. Lett., 16(1), 014014. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abcc28

Liu, T., L.J. Mickley, S. Singh, M. Jain, R.S. DeFries, and M.E. Marlier (2020). Crop residue burning practices across north India inferred from household survey data: bridging gaps in satellite observations. Atmos. Environ. X, 8, 100091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeaoa.2020.100091

Liu, T., L.J. Mickley, P.N. Patel, R. Gautam, M. Jain, S. Singh, Balwinder-Singh, R.S. DeFries, and M.E. Marlier. Cascading delays in the monsoon rice growing season and post-monsoon agricultural fires likely exacerbate air pollution in north India. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., in review.