Khyati Tripathi, the Mittal Institute’s Jamnalal Kaniram Bajaj Trust Visiting Research Fellow, is a psychologist and anthropologist from India who tries to bring together events, emotions and practices related to death to explore the psychosocial significance and intricate connections between them. She is interested in exploring the ‘sacred’ in death and the pure and impure aspects of it. Her work is based at the intersection of social anthropology, psychology, and psychoanalysis.

Khyati Tripathi is LMSAI’s Jamnalal Kaniram Bajaj Trust Visiting Research Fellow.

Mittal Institute: Thank you, Khyati, for sharing your work with us. What initially drew you to this field?

Khyati Tripathi: The ephemerality of life has always intrigued me, and more so when I lost a friend at the young age of 14. His death was hard for me to cope with in many ways. Firstly, it was my first encounter with the ‘tangibility’ of death as a teenager who was mature enough to understand death; and secondly, it pushed me into a cobweb of questions I had no answers to: what happens to us after death? Is there an afterlife? Am I going to meet him after I die?

As I became interested in these questions, I realized that very few people would engage in personal or academic conversations pertaining to death. I instantly felt drawn towards knowing ‘death’ more through people’s experiences (direct or vicarious)—of going through a terminal illness, of performing death rituals as mourners, of participating in the mourning rituals, of performing rituals as a death priest, etc.

Over the years, I have introspected and reflected on this quest of mine and have been able to understand that my work is also a way to intellectualize ‘death’ by helping me tame my ‘death anxiety’ pertaining to my significant others. We as humans cannot let go of the control, right? I think that’s what I am trying to do—seek some control on a phenomenon that is utterly unpredictable and uncertain. Ironic!

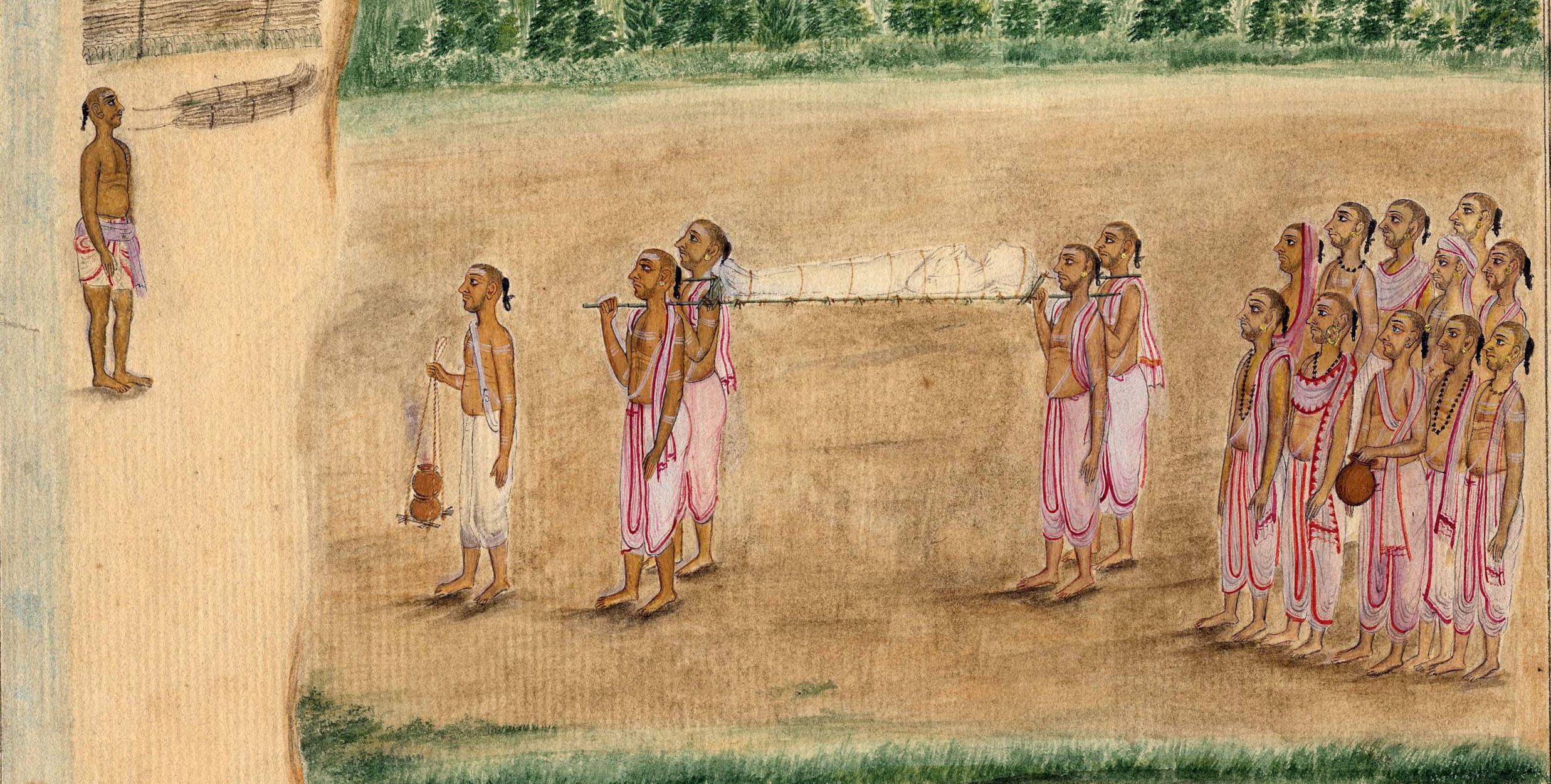

An 1820 painting showing a Hindu funeral procession in South India | Wikipedia.

Mittal Institute: Can you give us a high-level overview of the aim of your work? What aspects of death and dying are you most interested in, and what specifically are you working on while an LMSAI Fellow?

Khyati Tripathi: Through my work, I am interested in redefining how the concept of purity and impurity are understood in Hinduism in the context of death. As an LMSAI fellow, I am looking at how ‘impurity’ plays out in death work and if death work acts as a caste category in Hinduism. During my fellowship, I am especially invested in exploring the social status of executioners in India and what aspects of impurity are novel to the specific deathwork of judicial killing.

Mittal Institute: For some people, death is a taboo or morbid topic. What would you say to those people?

Khyati Tripathi: Absolutely, for some people it is and I would say that they are right in perceiving it that way. We are all wired differently. As a scholar interested in death studies, I believe I am adept at being in/witnessing certain situations that might not be very comfortable for others. Similarly, there are fields/spaces that are uncomfortable for me. I also believe that people take their own time to slowly fathom the impermanence of life and turn towards understanding, exploring, or “befriending” death thereafter at their own pace. It is the latent relationship with death that gradually comes to the surface; and while death still remains morbid for some, their ways of responding to it change.

I am looking at how ‘impurity’ plays out in death work and if death work acts as a caste category in Hinduism.

Mittal Institute: How have you seen death and dying practices change, for example, with the advent of “death with dignity” laws, or the recent COVID pandemic?

Khyati Tripathi: We saw a change in ‘deathways’ during COVID. While death unleashed its untameable side, we were unable to address it within the religious or social realm (through performance of death rituals, meeting the bereaved, through physical touch of the deceased’s body, etc.). At many junctures during the different waves of the pandemic, we witnessed how dignity in death was lost, especially when it became difficult to even see the loved one’s face one last time or when the plastic body bag was the only memory of the deceased the bereaved were left with. The faith-based death rituals, of course, play a pivotal role in bidding farewell to the deceased; they also help the bereaved cope after the death of a loved one. The sense of having been able to do something for the deceased brings psychological comfort. This is not to say that the rituals take away all the pain and that the grieving ends with the defined mourning period; rather, the rituals handover some control to the bereaved after the death has happened. With COVID, the sought or ‘illusory’ control was lost, which affected people in adverse ways.

Mittal Institute: You recently wrote a book chapter on Partition and the “nature of death.” The Mittal Institute has played a major role in capturing and archiving the voices of those affected by Partition. Your chapter talks about a range of deaths – physical deaths, social deaths, material deaths. Can you tell us more about this piece?

Khyati Tripathi: Yes, I wrote this chapter for the Routledge Handbook of Religion, Mass Atrocity and Genocide. Through this chapter, I have discussed how the alive bodies became ‘congruent’ or ‘incongruent’ during the partition. I explain how migration by millions was an effort to bring their bodies in a congruent state by stepping on the land that corresponded with their bodies’ religious identities. The state of incongruence was based on the physical presence of an individual on land ‘not meant for him/her.’ As I write in the chapter, “migration was symbolic of the struggle to transition from the state of incongruence towards congruence” (p. 152). In this chapter, based on the state of congruence or incongruence, I discuss physical deaths, social deaths (when you become socially non-existent), and death of material, i.e explaining how such things as homes die too, along with people.

Mittal Institute: How has your Fellowship with the Mittal Institute advanced your work? What are your future research goals, and how do you see your alignment with the Mittal Institute impacting this?

Khyati Tripathi: It is the rigour with which LMSAI focuses on South Asian research that drew me to it. I felt convinced that this is the place which will support me in bringing the research ideas (pertaining to death work) to fruition that have been marinating in my head for years now. I am thankful to the Mittal Institute for this fellowship that allows me to get on this journey of dissecting impurity further in deathwork in India with respect to the executioners. After my fellowship tenure at LMSAI is over, I plan to pursue fieldwork in India with death workers. The support, resources and mentorship at the Institute are unmatchable without which I am sure it would be difficult to accomplish my research goals.