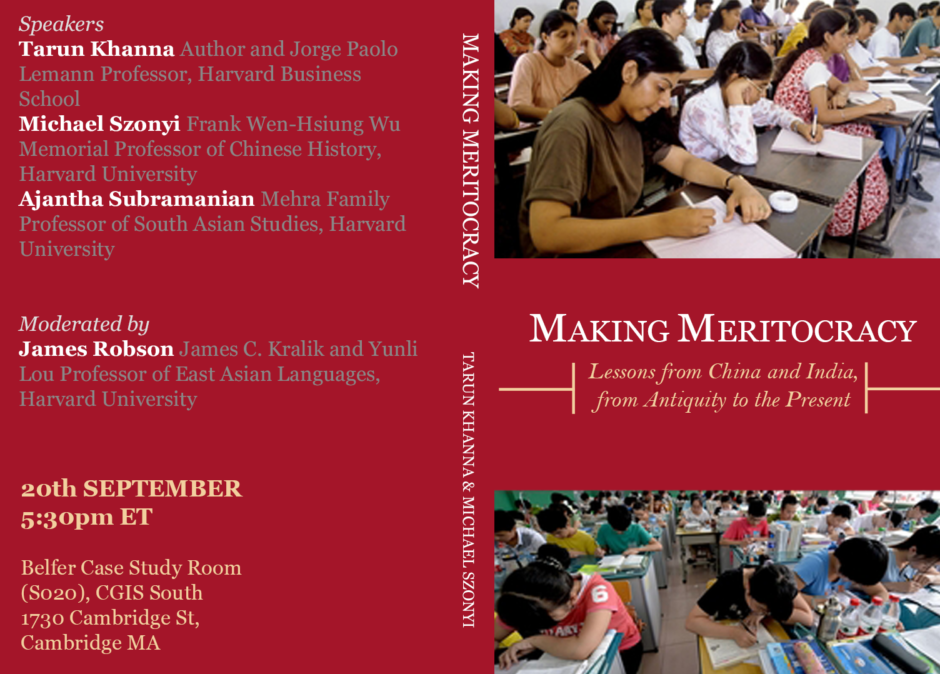

How do societies identify and promote merit? In their new book, Making Meritocracy: Lessons from China and India, from Antiquity to the Present, Tarun Khanna (Jorge Paulo Lemann Professor, Harvard Business School and Director, LMSAI) and Michael Szonyi (Frank Wen-Hsiung Wu Memorial Professor of Chinese History and Former Director, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies) explore how societies enable all people to meet their potential, and advance through their own demonstrated merit. Through more than a dozen essays by top experts, the book discusses how the two most populous societies in the world have tried to make meritocracy time and again through the centuries, but how those efforts have always met roadblocks, so that meritocracy is always a work-in-progress. Ahead of their September 20 book talk, we spoke with Professors Khanna and Szonyi about the book and the lessons countries around the globe can draw from it.

Mittal Institute: Congratulations to you both on the new book! Can you describe the evolution of your partnership – how and why did you decide to band together on this project?

Tarun Khanna: Obviously, for anybody interested in any fast-growing, rapidly-developing society, one of the central concerns naturally surrounds the issue of how we nurture talent and then ensure that talent somehow finds itself being used for the purpose to which it is best suited. I guess it’s even more so for university academics like us who are privileged enough to be surrounded by talent that we’re charged with nurturing.

I remember I had a serendipitous conversation in around 2014 about the examination systems that cause so much angst in both China and India between Mark Elliott, who is now Vice Provost of International Affairs but at the time was the Director of the Fairbank Center, and Wang Yi, who was running our Harvard China office in Shanghai. Somehow, we got around to convening a workshop at Harvard of scholars interested in this comparative topic. A lot of people from diverse disciplines attended, and that was sort of the kick off to the project.

Mark moved on to his administrative role in the Provost’s office, and Michael stepped in as Director of the Fairbank Center. And to my delight, Michael thought this was a good project to continue. I have had the pleasure of learning from him enormously. We hosted a number of workshops – in Beijing, Shanghai and New Delhi – and smaller workshops in Cambridge to refine the ideas. Out of a subset of the people who were involved with that from all disciplines, we identified a core group with whom we developed the outline of the book. So that’s the thumbnail sketch.

Michal Szonyi: This is a topic that drew people together. It engaged scholars working in an extraordinarily wide range of disciplines, from philosophy to history to sociology to economics to business. So part of the reason for the momentum of the project was that so many different people in different parts of Harvard and different universities around the world, and indeed, beyond the university, recognized the significance of the topic and jumped on board.

Tarun Khanna, Jorge Paulo Lemann Professor, Harvard Business School and Director, LMSAI (left) and Michael Szonyi, Frank Wen-Hsiung Wu Memorial Professor of Chinese History and Former Director, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies (right).

Mittal Institute: Why is it so important to analyze the meritocracy of China and India? Can you give readers a brief glimpse on how these respective countries currently identify and promote merit?

Michael Szonyi: This gets to one of the central motivations for the project. One of the things that makes the project significant is that meritocracy is such a very hot topic in the United States right now. And there are several important books coming out that talk about the problems of meritocracy in the U.S. However, the discussion in the United States often gives the impression that this is the first society that has ever had to confront the challenges of identifying and nurturing talent and meritocracy. And one of the things that makes China and India so interesting is that these are societies that have been pondering similar issues, analogous issues, literally for millennia – the question of what constitutes merit, of how to identify and nurture merit, how to reward merit. Not only is there an extraordinary philosophical tradition of reflecting on these topics, but also an extraordinary practical tradition of really trying to find optimal solutions. Having said that, the book and the project were not really primarily historically focused, although we ended up including a number of historians.

The discussion in the United States often gives the impression that this is the first society that has ever had to confront the challenges of identifying and nurturing talent and meritocracy. And one of the things that makes China and India so interesting is that these are societies that have been pondering similar issues, analogous issues, literally for millennia – the question of what constitutes merit, of how to identify and nurture merit, how to reward merit.

Also, China and India are the most populous countries in the world, so their methods and their success or failure at nurturing talent are extraordinarily consequential in an absolute sense. If people are not given equality of opportunity in places like China and India, that is a human tragedy of enormous scale and scope. If we accept the premise that the nurturing, identification and rewarding of merit is linked to economic efficiency and productivity, then if China and India don’t get this right, there is an enormous economic cost. But rather than simply framing it in terms of who gets it right or gets it wrong, there’s also the point that these three societies – that is China, India and Singapore, which is also mentioned in our book – may provide practical lessons for one another to deal with these challenges.

Finally, it matters because China and India are the sources of very large numbers of our students at all levels. And we want to recruit meritorious students, and we want to set them up for success, and we want them to succeed. And so understanding how merit works in the societies from which they come and to which they may return is immediately consequential to our work here at Harvard.

Mittal Institute: What are some of the lessons that readers can glean from the book?

Tarun Khanna: I approached this project, not being an historian, with very little preconceptions about what I would learn about the China and India of past times. As a self-described “analytic social scientist,” the way we learn is through variation in the data. And if all we are doing is looking at the U.S. context over and over again, we are collectively limiting ourselves and potentially drawing incorrect inferences about how meritocracy plays out.

So I approached this from a study design perspective, saying it would be really good to be able to, in the social science jargon, exploit time-series variation by looking at China and India over time. Plausibly, the China of 200 years ago is very different from the way meritocracy is thought up and organized in the China today – and ditto for India, and so on. And it is interesting to also explore contemporary cross-sectional variation between China and India, or different subparts of what are two continent-sized land masses, so to speak.

The really amazing thing was that, as Michael alluded to in his initial comments, it’s déjà vu. It’s the same issues over and over again. So not only is America unexceptional in the angst-ridden way in which we are daily litigating these issues on the front pages of The Crimson and the New York Times, but the very same issues are being societally litigated pretty much everywhere, including in India and China, including going back millennia. So, it’s really quite extraordinary.

Mittal Institute: You both are experts on these two countries, respectively. What came out of the research that surprised you the most ?

Tarun Khanna: One thing that was brought to the front of my consciousness much more explicitly was the realization that all our discussions of meritocracy are really about a relatively smallish percentage of the population. It’s about people who are in white-collar professions, right? And that’s extremely true of the U.S. debate, as well. You read some of these amazing new books – Daniel Markovits and our colleague Michael Sandel – they’re extraordinary books. But they’re really about the angst of Ivy League colleges or just beyond. And that’s such a tiny sliver of the talent mass.

And the same applies to China and India to varying degrees. And I just found myself thinking that there’s over a billion people in each of these countries – that’s a lot of people we are talking about. These days, we’re very much fascinated with the rise of the so-called gig economy. All these people are running around, doing all this stuff. What about the idea of meritocracy as an organizing principle for the bulk of society comprised of these vast masses of people, ultimately, whose productivity is the engine of growth? All our debates about meritocracy really aren’t explicitly embracing those. And I think, in a few of our essays, we had some of our colleagues bring those issues to the forefront. I thought that was a very different perspective.

Michael Szonyi: One thing that is very striking coming out of the book is that virtually all modern societies staff government offices through a combination of meritocracy and democracy to some degree. A great many people in government in the United States are not elected. They are appointed and then promoted on the basis of merit. And so what many might see as a binary between meritocracy and democracy as modes of selection in a society are really much more a set of options from which all societies pick and choose. This is true of China and India and the US

And to answer your question about what things struck us through the project, I think one thing that comes out very clearly from certain essays and the book as a whole is the way meritocracy is often presented as a question of techniques. That is, what are the policies? What are the principles by which schools should be organized, admissions should be organized? But in all three societies – and indeed, in all societies – meritocracy is wrapped up in questions of very fundamental values about how societies think about the individual, the relationship between the individual and their community, and about the kind of community we want to construct. So for me, this was both a striking observation, but also a cross-cultural and cross-historical finding regarding debates about meritocracy. Debates about meritocracy are often presented as if it was a narrowly technical question, but it’s never a technical question. It’s always a question about values, about what a society holds dear, about tensions within a society over different ways of defining values. And we see this again and again and again in the historical and contemporary context of India, China, and indeed, the United States.

Tarun Khanna: One way to make that concrete in my mind, Michael, is to think of this issue of what we refer to in the book as – I think it’s a phrase that you and I came up with – compensatory discrimination, right? And what I mean by that is if you look at any of these societies at any point in history or contemporary times, there are always a set of people who are privileged and a set of people who are materially or cognitively or psychologically left behind, right? And the issue then arises, is it right to provide extra societal favors to those who are seen as left behind, which those who are not left behind consider to be unfair at that point in time, so that things ideally would become more equal and fair in some hypothetical future? In essence, privileging of one kind of values as another.

Mittal Institute: And why was it interesting to look at Singapore? What did it offer you that India and China didn’t? What additional information did you glean?

Tarun Khanna: To my mind, Singapore, with Lee Kuan Yew as the societal sarchitect, I always think of it as the canonical example of an entity that is committed to the idea of meritocracy. And, of course, Singapore is managing a multiethnic state, so to speak, a city-state – predominantly Chinese and then some Indians and Malays – and is very conscious of racial tensions. And so, it always has to maintain amity across all. And one way to do that was to take a very technocratic approach and say, let’s construct a meritocratic society, which generally seems to have succeeded, at least in economic terms.

So the first item of fascination was to look at meritocracy as an organizing principle in our societies, and Singapore seemed like a very interesting case. Spatially, it’s also sort of “in between” China and India. And arguably, it would have been influenced both by what happened in China as well as in India, though in practice, I think it’s far more influenced by China than it is by India in any sense of the term – historically, anyway.

Singapore is also currently struggling because it finds itself in its own meritocratic contradictions and unable to escape them to reach what I think Singaporeans would describe as their desired higher levels of creativity. And so that itself is an interesting issue when you build a society based on commitment to a particular interpretation of meritocratic principles, and how difficult is the transition if you wish to move away from it? I think there were a lot of conceptual issues there that, to me, were very exciting…….. And I also love the food in Singapore. So that was another reason!

Mittal Institute: Are there specific lessons that can be gleaned for India and China, or maybe more globally, from Singapore as an example?

Michael Szonyi: Perhaps one is that meritocracy is, by definition, not an end-goal but a process, because definitions of merit are contingent and need to adjust and adapt to a changing political economy and to changing social structures. And so while Singapore stands out as a particularly successful example of implementing a meritocratic approach to education, it now finds itself in need of adjusting.

The second finding, which I think is actually a central lesson of the book, is that meritocracy must be a process in a somewhat different sense. In virtually all contexts where attempts have been made to create a meritocratic approach to education, the system is basically captured by elites. They take advantage of their privilege to ensure that their offspring are better positioned to meet the criteria that are being used to evaluate meritocracy. And so this elite capture issue is really striking because meritocracy in education is typically promoted as a way of undermining privilege. And yet it seems everywhere to entrench and reinforce privilege. And as we write in the afterword, a principle intended to undermine entrenched privilege results in the appearance of or the actual entrenchment of privilege whenever and wherever it is put into practice. This seems to be a central and perhaps universal paradox of meritocracy.

This obviously has lessons for any society that seeks to promote meritocracy. The process part of the story is not simply because you are going to conceptualize meritocracy differently when you are in an early-stage industrial economy from when you’re in a high-tech economy. You also need to deal with the internal contradictions of meritocracy. And Singapore, as Tarun said, is realizing that.

This obviously has lessons for any society that seeks to promote meritocracy. The process part of the story is not simply because you are going to conceptualize meritocracy differently when you are in an early-stage industrial economy from when you’re in a high-tech economy. You also need to deal with the internal contradictions of meritocracy. And Singapore, as Tarun said, is realizing that.

Mittal Institute: What’s one thing you’d like readers to take away from Making Meritocracy?

Tarun Khanna: It really places the American debate that’s playing out around us in a much broader context and makes it clear that it’s not something idiosyncratically American that’s driving these moral, philosophical, economic discussions, but something more fundamental, probably, to human nature.

Michael Szonyi: I would agree. Just to expand briefly, it is interesting to see how a debate that exercises so many people so much is indeed not historically specific to the United States at this moment but is perhaps even universal in complex societies. And it’s also interesting because, to come back to my comment about meritocracy touching on core values, it’s interesting that this is a topic that really can be approached from so many different angles. It’s a topic that lends itself both to trans-geographic comparison, which is why Tarun and I are collaborating on this project, but also to true interdisciplinary conversations. So it makes it very interesting as an academic subject. Our conversations at the workshops were fascinating because there really were ways in which political philosophers, historians, anthropologists, sociologists, and activists could talk about these issues together.