Tania Saaed, Associate Professor of Sociology at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), Pakistan, and Marie Curie fellow at Ca’Foscari University of Venice, Italy, recently arrived at Harvard as part of her Marie Curie Fellowship with LMSAI.

Her work focuses on comparative and international education, from exploring Islamophobia and securitization in the context of universities in the U.K., to the increasing securitization of education in Pakistan, and across South Asia. She spoke with the Mittal Institute about her work and fellowship.

Tania Saeed.

Mittal Institute: Tania, welcome to Harvard! What led you to apply for the fellowship in the first place?

Tania Saaed: Since 2008, my research has primarily focused on education, from my D.Phil at Oxford to the research and policy work that I have done in Pakistan. However, increasingly I have been drawn to questions beyond educational institutions—the kind of socialization taking place in communities and families that influence young people’s engagement with others—that is reflected in encounters of discrimination or acceptance within classrooms and schools. As a result, I started engaging more with political sociology in my work, while also realizing that I needed to expand my research training. That is where the Marie Curie fellowship comes in, which is precisely designed for researchers to grow their training, encouraging more interdisciplinary work. I have designed a project that builds on my doctoral work in the UK with the Pakistani and British Pakistani communities, including my research in Pakistan that was more focused on the politics of education, while expanding it to the American and Indian context, and bringing communities into focus. In the U.S, the only place I applied to pursue my Marie Curie research was Harvard’s LMSAI. There was no question about going anywhere else, given LMSAI’s exemplary scholarship on South Asia, which has been home to many of my colleagues and mentors. It is an absolute honor to be in their company at LMSAI.

Mittal Institute: What captivates you about educational systems – what drew you to examine them from the lens of social justice, inclusion and citizenship?

Tania Saaed: My interest in studying education systems has existed since I was an undergraduate student at LUMS. In fact, for my senior year thesis, I conducted interviews and surveys of nearly 300 female students and teachers across government and low-fee private schools in Lahore to understand the different ways in which patriarchy worked in the education system; not only what was taught through the curriculum, but also what was learned through teachers and how that shaped female students’ perceptions about themselves and their futures. As a young student myself, that experience taught me first hand about how such systems that should be a resource for future opportunities become yet another tool to control women’s place in society. That was also when I knew I wanted to pursue a career that would allow me to do such research.

My [research] experience taught me first hand about how such systems that should be a resource for future educational opportunities become yet another tool to control women’s place in society.

My interest at the time was focused more on learning about gender and feminism, which is why I went on to pursue an M.Sc in Gender, Development and Globalization at the London School of Economics; however, I did not want to enter academia without experiencing the world beyond, and that resulted in a different trajectory when I took up a research position at the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in Egypt. I was still doing research, primarily focusing on policy work around women entrepreneurship in the MENA region, on microfinance and SME markets, but my curiosity towards larger questions remained. That brought me back to academia, which is the only place where I could explore these questions.

My focus on citizenship and inclusion became more prominent in my doctoral work in education at Oxford. My research was about British Muslim female students with a Pakistani heritage, and overseas Pakistani female students’ experiences of Islamophobia and the British state’s counter terrorism agenda in their day to day lives across universities in England. I explored how different levels of religiosity (how the intersection between religion and ethnicity in a largely securitized context) informed their everyday existence. The work also captured the resistance of these students, as they actively challenged prejudice and Islamophobia in universities, on the street, with some planning to take up positions in politics or media (which they have). The work has been well received, and published as a monograph entitled “Islamophobia and Securitization: Religion, Ethnicity and the Female Voice” by Palgrave Macmillan’s Politics of Identity and Citizenship series. I carried on my research on citizenship and education when I moved back to Pakistan, and collaborated with Professor Marie Lall to explore similar questions of identity, securitization, and belonging for young Pakistanis, focusing on students’ perception of the changing nature of Pakistani society and their relationship with the state, the military, the education system, and their engagement (or lack of) with politics, and social media. The project resulted in a co-authored book Youth and the National Narrative: Education, Terrorism and the Security State in Pakistan, published in 2020 by Bloomsbury.

As you can tell in all my projects, centering on the narrative of the student is extremely important for me. We as research scholars who undertake such rich qualitative work have a responsibility to our particpants to ensure that we don’t co-opt their voice. That is also something I have learned while doing research on issues of social justice and citizenship: how to write in a way that truly does justice to my participants who have always been so generous.

As you can tell in all of my projects, centering on the narrative of the student is extremely important to me.

Mittal Institute: As the Marie Curie fellow, you are focusing on your ongoing research project called The Inter-Nationalist – can you give us an overview of this work?

Tania Saaed: The Inter-Nationalist explores the relationship of the Pakistani and Indian diaspora in the U.K and U.S. with South Asia, across generations, with a particular focus on politics. The project has two trajectories: the first one attempts to understand the different ways in which first and subsequent generations of immigrants engage with the country that was left behind, the memories, the joys and disappointments in going back, and their future hopes, as well as the home they found in the U.S and U.K. For this purpose, I have been interviewing parents and their children, as well as students who are part of Indian and Pakistani student societies, which so far has been an enriching experience. The one interview that I most enjoyed recently was with a 102-year-old remarkable woman in the U.S. from Pakistan, who has led an incredible life and was instrumental in providing girls education across Srinagar to Peshawar—narratives that would otherwise be lost. I am still in the process of conducting these interviews, and will be traveling across the U.S in the hopes of meeting the Pakistani and Indian diaspora.

The second one focuses on more direct political engagement through the case studies of the International Chapters of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) political party, and the Overseas Friends of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), to explore how they engage, why it is important, and what they hope to accomplish through such engagement. This part also examines concepts such as populism, transnationalism, and political remittances. While more scholarship exists on the Indian diaspora, and in particular on the BJP overseas, there is limited work on political engagement of the Pakistani diaspora. The PTI has been more active in trying to work with the Pakistani diaspora than any other Pakistani political party, which is why I chose to focus on PTI. My fieldwork in the U.S. will end in January, after which I will spend three months in the U.K conducting interviews with the diaspora community there. I will be working on academic publications, including a manuscript, but I also hope to be back, because there is a lot more to explore here and I feel like I am just beginning.

Mittal Institute: Some of your other recent work has focused on the ideologies of exclusion in education, particularly in Pakistan. Can you share an overview of any of these projects that you’re working on under this topic?

Tania Saaed: There have been quite a few projects that I have been working on, ranging from exploring ways in which particular identities are included or excluded in the curriculum; teaching across different types of schools including government, low fee private and refugee schools in cities and refugee villages; to understanding the structure and functioning of the neoliberal university in Pakistan. However, the one that I am incredibly proud of and would like to highlight is the Education Justice and Memory (EdJAM) network that is led by Professor Julia Paulson at the University of Bristol, where I have been co-Investigator since we applied for the grant in 2019. The network is funded by the U.K. Research and Innovation (UKRI) Global Challenges Research Funding (GCRF) Collective Programme. EdJAM brings together artists, activists, researchers, civil society members, heritage sector professionals, students and teachers across 13 countries (Pakistan, Uganda, Cambodia, Columbia, Jordan, Argentina, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mexico, Peru, Jamaica, South Africa, Palestine and the U.K) to explore creative ways to teach and learn about violent pasts (EdJAM 2022). In Pakistan, our team has been working with Shehri Pakistan, a social initiative run by the incredibly talented Arafat Mazhar, who has produced short animations on violent historical events that are seldom discussed in mainstream curriculum, from British colonial rule to the anti-Ahmadi violence of 1953. Called Hashiya Online, these videos are freely available for viewing.

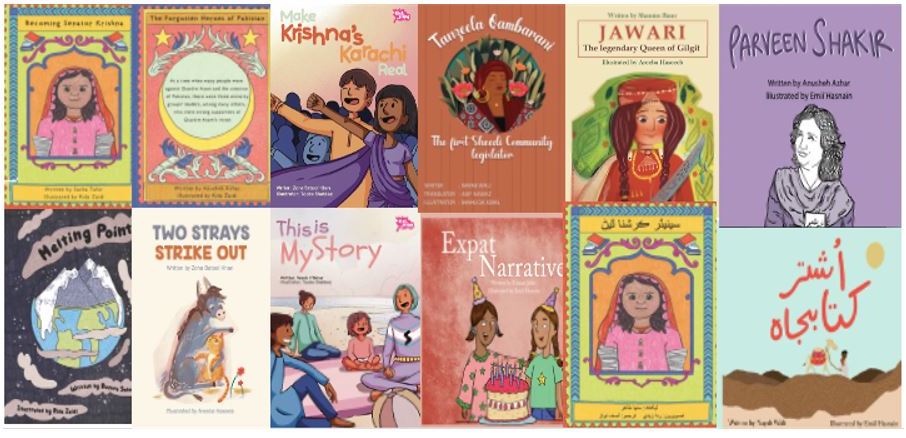

As part of EdJAM, we have also worked with students and young local artists to produce short illustrated books for children. The Pakistan Children’s Series highlights stories that are missing from mainstream curricula on topics such as the climate crisis, animal rights, land rights, gender and sexualities, the role of leaders from religious and ethnic minorities, among others. These books were researched and developed by our students, and illustrated by young artists from across Pakistan. They are also open source. Around 2,000 books have already been distributed across schools.

Examples from the Pakistan Children’s Series.

I wanted to highlight this project in particular because of its interdisciplinary nature and its emphasis on collaboration across sectors for more social impact. Our EdJAM framework engages more theoretically with bell hooks ethic of love, together with our EdJAM values. I won’t go into detail, but if your readers are interested, we have a forthcoming chapter, “Values and the possibilities for minimising epistemic injustice in international collaborations: reflections on bell hooks’ ethics of love from the Education, Justice and Memory Network (EdJAM)” in the edited volume by T. Archer, B. Hajir, and W. McInerney, Innovation in Education and Peace Praxis, published under Routledge’s International and Comparative Education Series.

Mittal Institute: What are you most looking forward to during your time in Cambridge?

Tania Saaed: There is a lot I want to do, and have been doing since I arrived. I’ve attended seminars, explored libraries, and just enjoyed walking around the campus. But what I did not expect was to meet such a wonderful cohort of fellows at LMSAI. I have learned so much from my conversations with other LMSAI fellows Ajmal, Aamina, Khyati, Sharbendu, Liaqat, Yaqoob and Ian, about current events in South Asia, thinking through religion, culture and of course food, you know when you have a bunch South Asians food is a central part of the conversation. I have also met some wonderful fellows from other departments during the Fellows orientation, friendships that I did not think were possible at this stage of my career. It continues to be an enriching experience, and I hope I continue to learn and grow during my time here.

Mittal Institute: Do you have any other research projects on the horizon?

Tania Saaed: There are a few projects on the backburner that I will be returning to after the fellowship. But in the meantime, I have two edited volumes coming out next year. I am a guest editor for Palgrave Macmillan’s South Asian Education, Policy, Research and Practice series, that is run by Radhika Iyengar, Matthew A. Witenstein, and Erik J. Byker. Our upcoming volume is entitled The Politics of Education: Exploring Education and Democratization in South Asia, that brings together established, early career scholars, students and teachers who engage with the socio-political changes taking place in South Asia and its implications for education and democracy. This will be out early next year.

The second edited volume is with Dr Marcus Otto who is based at the Leibniz Institute for Educational Media, and the Georg Eckert Institute in Germany. The book, Critical Perspective on Integration in Education. Grassroots Narratives from Multiregional Settings, brings together policy makers and academics from across the Global North and South to think through the notion of integration in/through education for displaced communities, refugees, immigrants and minorities, essentially members of those communities that are either excluded from mainstream schooling, or their experiences are silenced for the purpose of greater integration through education. The edited volume will be out around the middle of next year, published by Bloomsbury UK.