Clockwise from top: Chhimtuipui and Tuipui river of Mizoram; A Tiwa tribal woman of Meghalaya; Nagas of Nagaland rehearsing a traditional dance | Wikipedia.

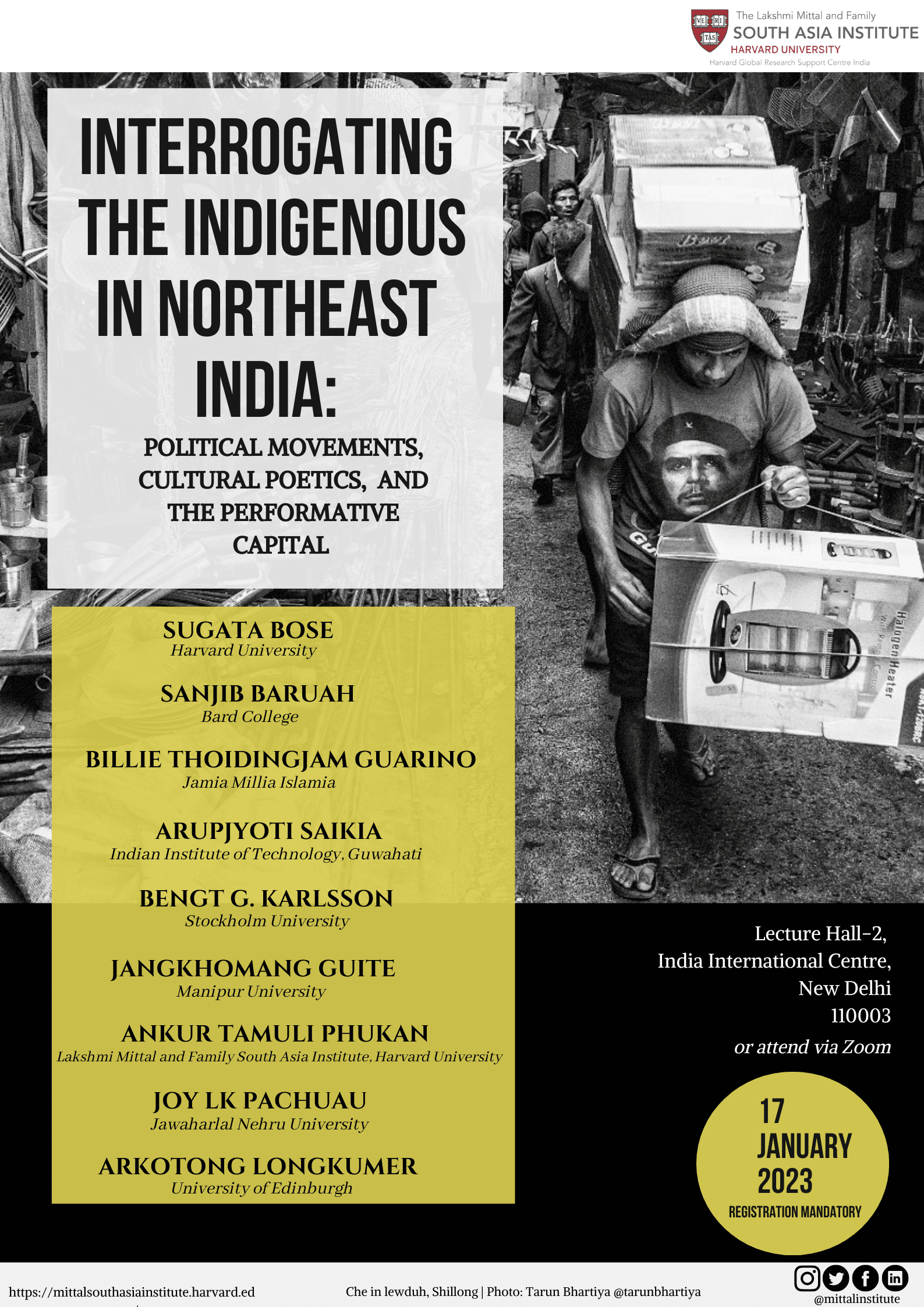

On Tuesday, January 17 the Mittal Institute will host the “Interrogating the Indigenous in Northeast India: Political Movements, Cultural Poetics, and the Performative Capital” conference, which will trace “indigenous” as a historical category, investigating the ways in which the indigenous question has become a shared language of social critique in Northeast India. The conference will begin with a keynote lecture on “Indigeneity and Contemporary Northeast India: History and its Contingencies” by Professor Arupjyoti Saikia, Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati. The session will then move into two panel discussions: Vernacular Politics, Ethnic Sovereignties and Politics of Hills and Plains; and the Indigeneity and the Politics of Performance. Attendees can register to attend in person (Lecture Hall-2, India International Centre, Annexe Building New Delhi,110003) or via Zoom.

We spoke with conference convener Ankur Tamuli Phukan, Mittal Institute India Fellow based in our Delhi office. Ankur works under the mentorship of Sugata Bose, Gardiner Professor of Oceanic History and Affairs at Harvard University, who will chair the keynote and a second panel discussion. Ankur shared the motivations behind the conference, and what he hopes attendees can glean from the panel discussions.

Mittal Institute: Ankur, thank you for speaking with us about this conference. As a historian, your research interests lie at the intersection of populism, nationalism, citizenship and migration. How did your work as an LMSAI fellow lead you to coordinate this conference?

Ankur Tamuli Phukan: Given my particular interest in Northeast India’s political and social processes, I learned to be aware of the significance of politics of identity and recognition in the region. In the last four decades the region has witnessed massive mobilizations around issues of identity and recognition, along with the brutal counter-insurgency operations by the Indian state. In the contemporary moment these trajectories have constituted indigeneity as the shared language of social critique in the region.

As an LMSAI fellow, I have attempted to unearth the essence of this new phenomenon by tracing the technology of its production within a specific historical time frame. I have had the privilege of reading some very new, emergent and interesting works in the field, so I thought it would be nice to think collectively. I am glad that some of the best minds in Northeast Indian studies have accepted our invitations and we are very much looking forward to collectively discussing the structure of indigeneity in Northeast India in the conference.

Mittal Institute: Can you give us a brief overview of the history of the term “indigenous” as it arose in the 20th century, and the shift that’s taken place in recent times?

Ankur Tamuli Phukan: The circulation of the idea of “indigenous” is a very recent phenomenon in Northeast Indian politics. Just ten years ago, you would have found terms or identity articulations like ‘tribal-local’ dominating the political and social psyche. However, at that point, there was a hesitant—but nonetheless serious—conversation aimed to create some sort of a space where the so-called “other,” or the “non-local” could also claim their membership within the structure of the mainstream Northeastern society. This has changed in recent times as a very rigid, simplistic binary of indigenous/settler, insider/outsider, or tribal/non-tribal has emerged as fundamental identity assertions in the area. Of course, there have been no more attempts of ethnic cleansing, rioting or intense insurgency and counter-insurgency operations like we witnessed in the past, but this strict and emerging binary has also triggered a different method of mobilization with a rigidity that is sharp and constant.

This is a change that I feel calls for serious academic engagement.

Mittal Institute: Can you tell our readers why it is critical to interrogate indigeneity in Northeast India? What do you hope the audience can take away from this conference?

Ankur Tamuli Phukan: I believe indigenous identity—or any identity, for that matter—is not a phenomenon beyond time. It has its own time map and thus can be traced to historical shifts and changes. For instance, without British colonialism and their classificatory politics of space and people in this area, we would have something completely different in terms of locating our own identity, as well others. If we believe in this foundational historical rationality, then tracing the historical and technological strategies of constituting a certain identity is significant in order to understand and, possibly, unsettle the existing politics and to collectively think for a different future. We hope the conference will be a step in that direction.

Mittal Institute: The first panel will explore the vernacular discourses found among the hills and plains of Northeast India, and what effect this has had on modalities of indigeneity. Can you expand on this and give us some insight into what this panel might explore?

Ankur Tamuli Phukan: Along with vernacular politics, the panel will also discuss its co-constitutions with different community sovereignties, and their shifts and changes with neo-liberal resource politics, which has created new modalities of indigeneity in the region in recent times. Such modalities have triggered some creative anxieties regarding our understanding of the relationship between hills and plains, the way we live, the way we think about our present and the future. From this standpoint we hope to discuss the region situating it in the Indian state context—the Northeast of India as it is called.

Mittal Institute: You are participating in the second panel, which will explore how indigenous identity is performed through different political movements, in historical trajectories, and ecological imaginations. What questions do you hope to probe during this discussion?

Ankur Tamuli Phukan: Here we are looking for technologies or the scripts and grammars of indigeneity in the particular context of Northeast India. For instance, in a political movement there are different scripts and grammars of performance. In serpentine public rallies, in rioting, in revolutionary festivals, one performs through certain script(s) or grammar(s). These performances constitute some codes, some fundamental sensibilities that are distributed time and again. That is why we see a conceptual similarity between a rioting and a festival staging at the same time in the expression of anger and joy. This session will hint at these technologies of performance as significant aspects of constituting a shared language of indigeneity in the region.

Mittal Institute: What are your research goals following this conference? Will you continue or expand the conversation?

Ankur Tamuli Phukan: Yes, I would like to continue with this for a while and possibly, try to expand the conversation both in Northeast academia and in the popular discourse.