Throughout its 150th anniversary year, Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences’ GSAS Voices is foregrounding the stories of some of its most remarkable alumni and students as they speak about their work, its impact, and their experiences at the School. Diana Eck, PhD ’76, is a Mittal Institute steering committee member and professor of comparative religion and Indian studies at Harvard University, where she also served as a faculty dean of Lowell House. Eck talks about her decades of work studying the religious traditions of India, the founding of the Pluralism Project, and how she learned to teach as a student at GSAS.

“I first became intensely interested in studying religion when I was an undergraduate at Smith College. I had started out as something of a political science fanatic, but as an undergraduate I got the chance to study and live in India for a year. I lived in Banaras, a sacred city on the banks of the Ganges River. When I returned from India, I continued to study India’s complex religious life.

While at GSAS, I returned to Banaras for a long research stint and wrote my PhD dissertation on the city. That became my first book, Banaras: City of Light. After I graduated from GSAS in 1976, I continued working in India and focused on pilgrimage sites the rivers, the headwaters, and the shrines all over India that are special places for pilgrims who seek their spiritual benefits.

Later on, I turned my questions inward, asking what my time studying India meant for how I think about my own faith. The book that came out of this questioning, Encountering God: A Spiritual Journey from Bozeman to Banaras, turned out to be important to many people who wrestle with issues of faith in the presence of other ways of being religious.

In 1990, I took what I had learned from my studies of Indian religious life and put it to use in America through the Pluralism Project, an initiative that explores the changing religious landscape of the United States. As the nation becomes more diverse, how do people from different religions and cultures come together, so we as a nation can better understand each other. How do those of us who are Christians or Jews encounter our neighbors who are Muslims or Hindus or Buddhists? And vice versa.

For several years, I had student research assistants travel back to their hometowns and map out the religious communities there. When they returned in the fall, we held seminars on what they had learned. My book New Religious America was based on that work and the ongoing research of the Pluralism Project.

A lot of people are still waking up to the fact that there is so much religious diversity in America. It’s important to continue to build interfaith infrastructure and bridges between religious communities to combat rising suspicion and fear.

Diana Eck on a research trip to India in 1973.

Mapping Multi-religiosity

Over the last six to eight years, I and my assistants at the Pluralism Project have translated our research into case studies that explore the challenges of religious diversity experienced by people throughout our society, whether in academia, business, government, or their home communities. They’re the basis for my undergraduate general education class, Pluralism: Case Studies in American Diversity.

For example, a large Sikh community in El Sobrante, California, holds a festival parade. A Christian pastor arrives and begins distributing leaflets telling the Sikhs that they will go to hell if they don’t accept Jesus Christ as their savior. In class, we discuss this case. How do Sikhs respond to the pastor’s behavior? How do other Christians respond to the Sikhs and to the pastor’s proselytism? How do people in the wider community understand and deal with the situation? When might proselytism become hate speech? Students come away from the class retaining a lot more about these issues than if I were just giving a lecture.

Diversity is not pluralism. Diversity is simply a fact, but pluralism is a creation, an ethic of dealing with diversity. I use case studies to put students on the ground, encountering the dilemmas of diversity. Of course, there are people in this country who still believe that America is or should be a Christian nation, or that Christianity should be privileged. But I think we all have an obligation to look the reality of our religious diversity straight in the eye and say, “This is who we are. Let’s get used to it. Let’s meet one another. Let’s get going.”

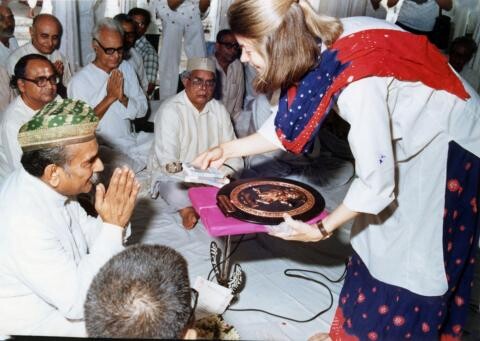

Diana Eck receives an award from the Maharaja of Kashi for work in the sacred city of Banaras.

Learning to Educate

I was lucky to go to Harvard as a graduate student and a teaching fellow when Derek Bok was president; they eventually named the Bok Center after him, and for a good reason. He was the one who convinced me that case study teaching was important, and he sponsored workshops for young teachers, in which our cases dealt mainly with education. How do you handle a class when someone’s hogging all the airtime, or someone’s not able to speak at all, or when you feel like you lose control of the discussion?

I struggled for years to figure out how I could apply what I learned in these workshops to teaching about other things, and when I finally did, I realized just how grateful I was to Derek Bok—long before the Bok Center was named after him.”

Photos Courtesy Diana Eck. Article reproduced with permission from Harvard GSAS and Diana Eck.