Deep in a bank vault of Mumbai’s Asiatic Society lies a revered treasure that is much studied in textbooks but rarely seen. The early 16th-century painted manuscript (dated 1516 CE), one of the oldest of its kind in the world, requires a committee’s approval to see the light of day – a committee that had remained elusive to Prof. Jinah Kim, an expert in South Asian art, for years. But last September, her proposal to study the painted manuscript finally got the go-ahead, and capturing the color from the rare piece of work may just change the study of South Asian art – and maybe all of Asian art – forever.

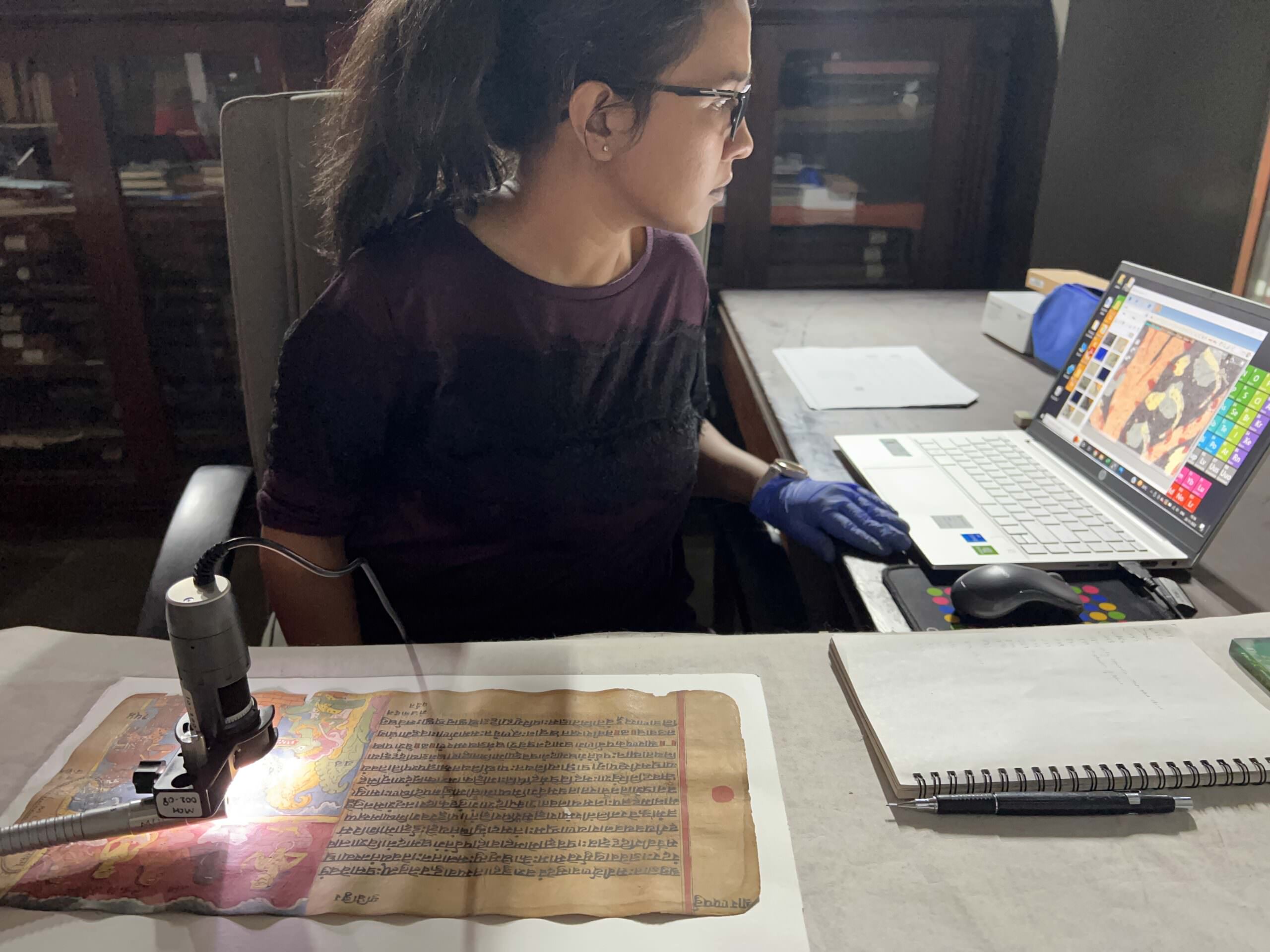

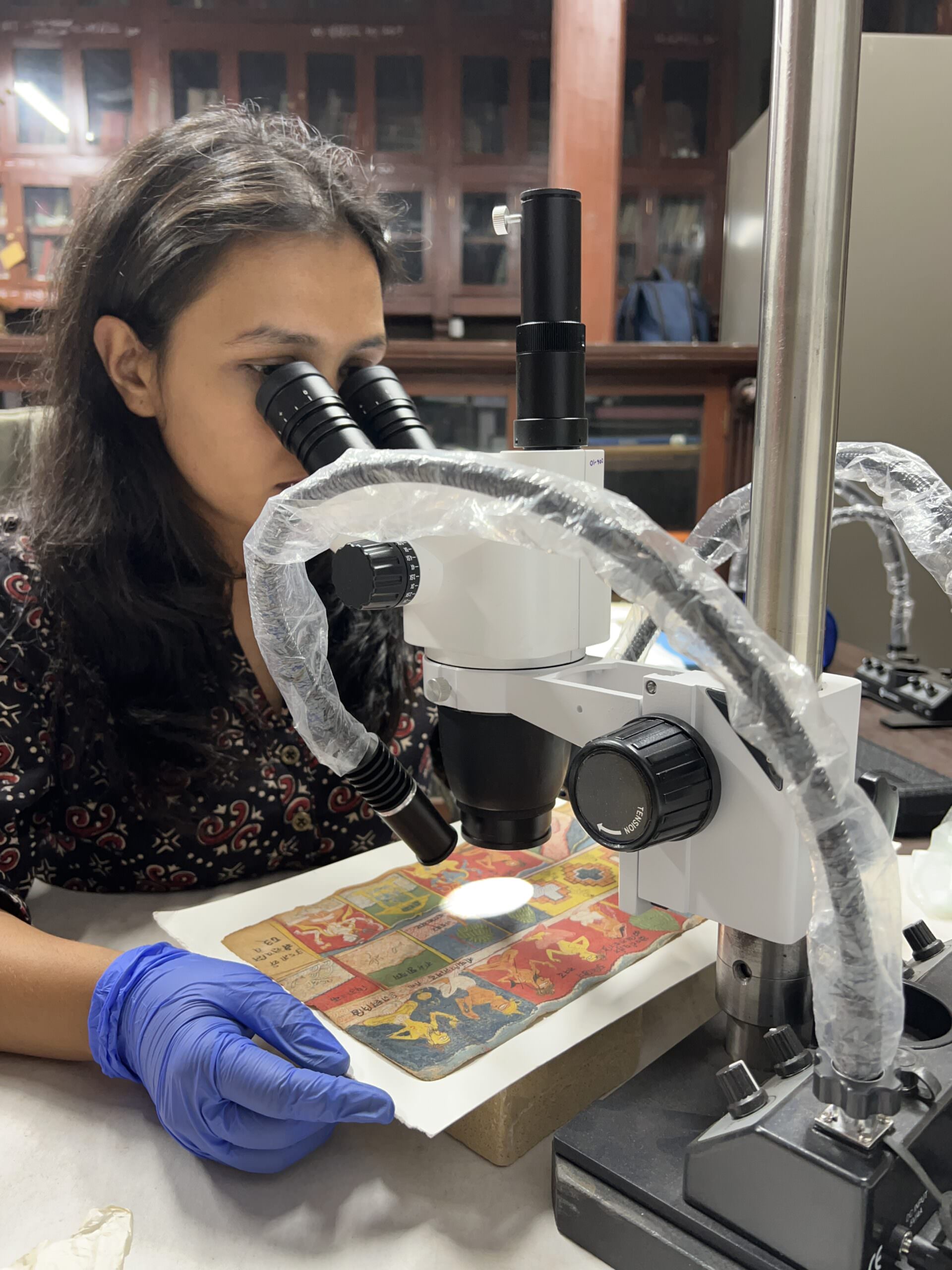

Left: Early 16th century manuscript being examined under Dynolite digital microscope, Nov 28, 2022, Asiatic Society, Mumbai; Right: Anjali Jain (MCH-India project coordinator/conservator) examines the early 16th century manuscript under the optical microscope, part of the MCH mobile heritage lab, Dec 6, 2022

Kim has embarked on an ambitious project to create a new object-based pigment database that upends the traditional Western knowledge base. The Mapping Color in History [MCH] project is a searchable, open database for historical research on pigments that has started with South Asia but with the potential to expand much beyond. MCH brings together scientific data drawn from existing and ongoing material analyses of pigments in Asian paintings in a historical perspective.

“There is no baseline knowledge on the history of pigments in South Asia; it’s all based on what is known from the Western art,” says Kim. “If you look at the history of pigment usage over time, there are databases out there, but those are all very much pigments based on the Western European canon of art.”

Jinah Kim, George P. Bickford Professor of Indian and South Asian Art in the Department of History of Art & Architecture at Harvard.

She realized this gaping hole while researching her second book, Garland of Visions: Color, Tantra, and a Material History of Indian Painting. While working on the material history of Indian painting, Kim wanted to go deeper into what people were using. She began talking to different conservation departments across different institutions and realized there was a lot of research being done but not being widely shared.

The MCH platform aims to change that. It gets experts from different disciplines talking and exchanging and, perhaps, even working together. Color, says Kim, provides many clues that can be unlocked by many fields. The global database can trace transcultural contact through the movement of colorants, artistic practices, and exchange across Asia. Users are able to search a large collection of paintings by pigment and see where and when particular pigments were in use for what types of paintings.

Color, says Kim, provides many clues that can be unlocked by many fields.

For instance, according to Kim, if you browse by color, in yellow, you will see orpiment is the most dominant yellow pigment registered so far, followed by Indian yellow, that famous organic pigment made of kettle urine. “You can also browse our pigment data by elements, from which, you can see mercury (Hg) is the most common element (the chemical composition of vermilion is HgS)” adds Kim, “and arsenic (As) is the third common element, which are, of course, considered quite toxic in today’s environmental standards.”

Measuring twelfth-century palm-leaf manuscript for condition report, MCH-India project at the Asiatic Society, Mumbai, November 16, 2022.

To bring the database to life, Kim, the George P. Bickford Professor of Indian and South Asian Art in the Department of History of Art & Architecture at Harvard, has engaged a truly interdisciplinary team of collaborators that includes research assistants, scientists, curators, conservators, specialists in conservation science and art history, and even software engineers. The list has grown so large that she has created an organizational chart to keep track.

“MCH is trying to help people appreciate the connection between art and science and bridge the two disciplines,” explains Kim. “Conservation scientists are talking to people who are interested in conservation science or conservators who are actually using this data to understand their material rather than art historians who are deeply invested in understanding the history. These two rarely overlap or talk to each other.”

MCH is trying to help people appreciate the connection between art and science and bridge the two disciplines.

Building the new color database is no small endeavor. The project has received support from the Faculty of Arts and Science at Harvard, the Mittal Institute, the Radcliffe Institute, and the National Endowment for the Humanities – and continues to grow and expand. Kim also finds there is no better place than Harvard from which to build the project: the Harvard Art Museums (HAM) and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts have rich collections of South Asian art, and the HAM’s Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies has been a “true partner” in the endeavor, as well, lending time and expertise along the way.

In India, Kim has collaborated with several institutions, including the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS). She works closely with the museum’s conservation team, sending curated lists of historically important objects, who, in turn, conducts analytical research on the objects and shares the data for the MCH team to interpret and inform MCH’s database. This year, the MCH-India collaboration will grow further with the MCH Mobile Heritage Lab, which will travel to collaborating institutions for on-site research and documentation.

MCH mobile heritage lab in action – Professor Kim and the MCH graduate student research assistants Victoria Andrews and Akarsh Raghunath examining fifteenth-century manuscript folios in the Bharat Kala Bhavan collection . Image courtesy of Bharat Kala Bhavan, Banaras Hindu University.

Kim’s own interest in South Asian art started with a class in college in South Korea, where she was on her way to studying literature. “I didn’t even know art history existed in high school,” she says, but recalls the class at university being transformative. At first, she thought about studying archeology but didn’t think “digging shards of pottery and making diagrams” suited her. “I think you need to be very patient, and I just didn’t think I had it in me.”

Her new focus was solidified during a college field trip to Pakistan in the 1990s and then later on trips to India. “I almost felt like, especially when I was living in India for a year for my field research, that when people would invite me to their homes, I felt like I was going to my grandma’s house. It felt like I was destined to be there.”

At Harvard, Kim’s research and teaching interests cover a broad range of topics with special interests in intertextuality of text-image relationship, art and politics, female representations and patronage, issues regarding re-appropriation of sacred objects, and post-colonial discourse in the field of South and Southeast Asian art. Her ongoing research projects concern three main areas: materiality in Indian painting, representation of donors and ritual scenes, and cross-cultural exchanges across Buddhist Asia.

She has many future plans for the Mapping Color in History project. Although the initial data collection is focused on Asian, especially South Asian and Himalayan, materials, in order to address the existing lacuna in the knowledge about historical pigments, the MCH’s database model will aim to accommodate data from any geographic locations and cultures.

As for the 16th-century manuscript and what she hopes that will add to the database. “It’s really incredible. This really will expand and challenge our understanding of painterly practices in South Asia.”