The Mittal Institute awarded funding to more than a dozen summer grant recipients, who have been busy pursuing fieldwork, language study, and research projects across all corners of the globe. Here are a few of their stories – for more accounts, stay tuned to our Twitter and Instagram.

Applications for Summer 2024 funding will go live this winter, with a submission deadline of February 2024.

Ashutosh Bhuradia, Harvard Graduate School of Education 2026

Research Project: Misperceptions about Caste and Attitudes toward Affirmative Action Among College Students in India

“There is a certain energy among Indian youth that is unmistakable. This is evident in interactions both big and small—focus groups, interviews, or students simply walking up to me after a survey and talking about their life, their aspirations, and their views on higher education policy. Though my pilot research work in India was undoubtedly challenging—for instance, running around offices to secure institutional support for my survey—it was imbued with idealism that feed offs of youthful energy.

I spent most of my time in central India. I conducted a pre-pilot at a large private university in India and then a pilot at a large skills development program for (mostly disadvantaged) youth. I had the opportunity to interact with dozens of students. Students engaged in thoughtful conversations about caste and the role of affirmative action in higher education in India (the topic of my summer research). I shared my perspective based on research and they shared their based on their lived experiences. I enjoyed the candidness of our conversations and learned something new every time I spoke with a different group of students. My research—and my perspective about caste in general—is more nuanced now because of these interactions. India has a large and diverse population of youth. They are both our source of hope and consternation. Hope because they are young, hungry, and eager to learn and work. Consternation because there is a sense that the system is failing them. However, as I reflect on my summer research, it is hard not to come away from India with scales tipped in the favor of hope.

Besides deep and meaningful interactions, my India trip also offered some lighter moments. I traveled to Delhi during the trip and visited the Lakshmi Mittal Institute’s India office and met the wonderful staff there. Delhi also offered opportunities to eat some of the most exquisite food in the world—from Mughlai food in Old Delhi to chaat and street food in the north. As the monsoon arrived, I traveled from north to central India via the Indian railway, taking in the lush landscape of rural India with its intermittent sights of cattle, birds perched on transmission lines, and endless green fields awash in rain.“

Clare Anderson, Doctor of Philosophy, 2024

Research Project: Tropical Agriculturists: The British Colonial Office, Imperial Agriculture, and the Global Tropics

“July in Sri Lanka has been a delightful whirlwind of meeting colleagues, delving deeper into the archives, and getting to know the countryside better. The first week of the month, I attended a three-day conference hosted by the American Institute for Lankan Studies (AILS) in Colombo, where I got to meet fellow historians working on various aspects of Sri Lankan history from Sri Lanka, the United States, the Netherlands, India, the United Kingdom, and beyond. We went on an excursion one morning to Tulana Research Centre for Encounter and Dialogue, where AILS is currently funding an inventory project of their massive and eclectic library. We wandered the stacks and listened to stories from the Jesuit priest director about running the center during the Sri Lankan civil war. Many conference attendees were still in Colombo the following week, and all ran into each other at the National Archives in Independence Square! It was great to be able to continue discussions over archive lunches, and learn about the different types of records everyone was working with.

I spent the second half of the month up in Kandy, where the Department of National Archives maintains a subsidiary branch. I discovered during my last research trip to Sri Lanka that the Kandy branch has a sizeable holding of colonial era Department of Agriculture records in their collection. My dissertation project looks at colonial agricultural institution-building and experimentation between several British Crown colonies (Sri Lanka included) around the turn of the twentieth century, so it was wonderful to be able to spend a solid stretch of time in Kandy! I managed to get through all the agricultural director diaries in the collection, which will set me up well to write this fall. The archive is up a nondescript side street behind the Sri Dalada Maligawa, an important Buddhist temple which houses a relic of the Buddha’s tooth. The temple maintains an elephant stable further up the road from the archive; several times a day, stablehands walk elephants back and forth right past the archive door! You can hear their bells jingle as they pass by.

This past weekend, I took the train up to Ella, a mountain town in the highlands of Uva Province famous for gorgeous views and nice hiking. I hiked Ella Rock on Sunday and was fascinated by all the different landscapes I encountered, and the subtle stories they presented about the interaction of agriculture and environment. Rice paddies near the rail tracks turned into tea plantations a little further up, and there were bits of grassland and native vegetation as the trail got steeper. To my interest and surprise, the whole forest on top of the mountain was a eucalyptus plantation (eucalyptus is an Australian tree), maintained by the Sri Lankan Department of Forestry! I saw several Caribbean pine plantations nearby as well. It’s fascinating to see how various plants moved around the world by colonial scientists have become normalized features in the Lankan countryside. As in other formerly-colonized countries, the desirability of continuing to cultivate non-native trees in forest reserves is very much under debate; it will be interesting to see what becomes of this in the future.”

Getting dinner with several new graduate student friends after the AILS conference, at a restaurant in Colombo that was previously the studio of famous Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa (Clare is in the center).

A temple elephant walking past the door of the archives in Kandy.

Exploring the stacks at Tulana Research Centre.

Atul Bhattarai, Harvard Divinity School, 2024

Research Project: Exploring Theravada Buddhism in Nepal as a Religious Identity

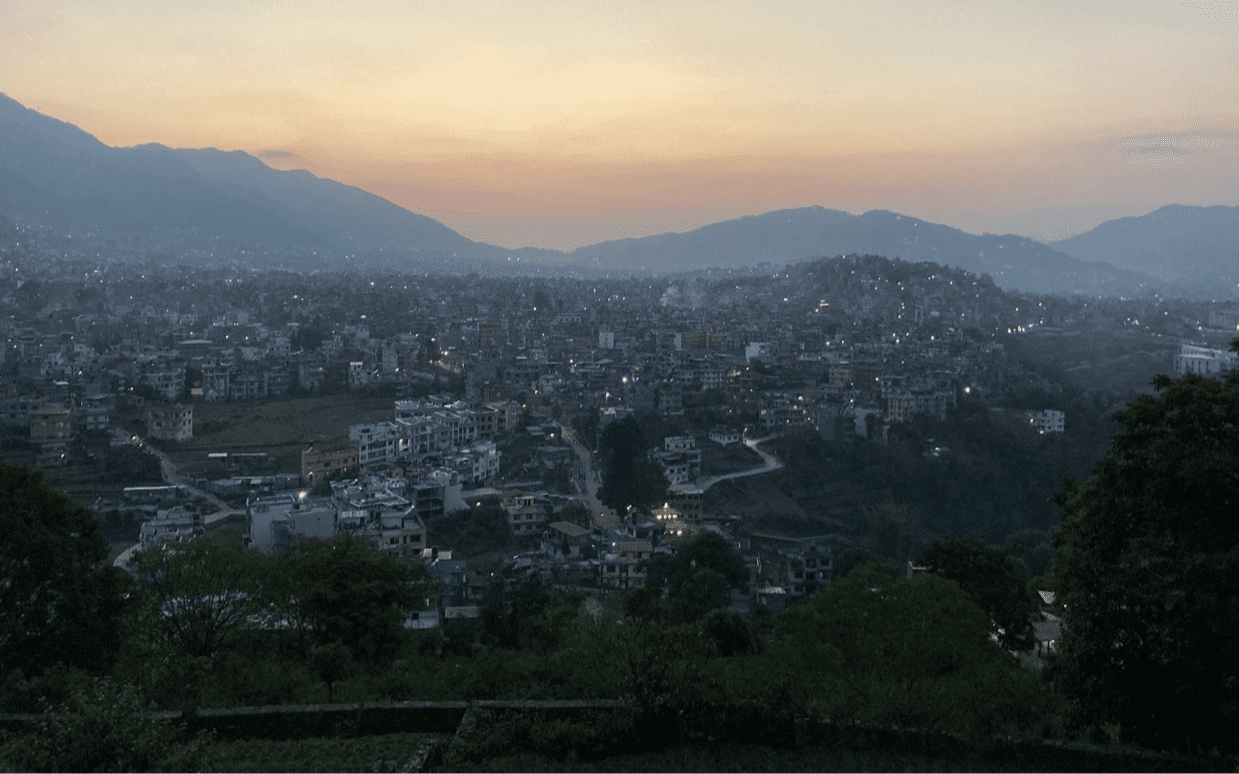

“It was wonderful to have the chance to explore Lumbini for the first time this summer! It was a definite highlight of this project. I’ve been fascinated by the Theravada movement in Nepal for years, and this was a great opportunity to delve into its reformist origins and recent shifts during my weeks in monsoon-touched Kathmandu. But Lumbini, thought to be the birthplace of the Buddha Gautama, has long had a pull on me, and visiting was one of the most academically valuable and personally moving experiences of my summer project. So many Buddhists around the world have mentioned having visited after learning that I’m Nepali. Located in southern Nepal – about 30 km from the border with India – Lumbini was a climactic shift from Kathmandu. While I was there, the temperature hovered around 43 degrees Celsius, enough to make you sweat as soon as the sun touched your skin, and was building into the beginning of the hot winds, the “lu” – which, I was distressingly warned by multiple people I interviewed, is said to make people bleed out of their ears.

Thankfully, I managed to explore the Lumbini gardens without incident, trusty umbrella-parasol in hand. I spoke in Lumbini to monks of the Theravada order in Nepal and officials at the Lumbini Development Trust, who were kind enough to give me leads and talk about the shifting forces in the Theravada movement today. Walking around, I got to visit large temples of many Buddhist traditions across the world, which here are all gathered in one place – a Thai temple and monastery near a Korean one, an Indian temple across the way from a Japanese and Singaporean one – and went on a dusty wild goose chase for a cavernous half-built Tibetan monastery. These temples, in various stages of construction and use, are arranged around a central canal. At one end was a structure housing an “eternal peace flame.” A nearby sign said that the flame was “promoted by Nepal Oil Corporation Limited.”

One of the most affecting moments in Lumbini was exploring the complex of the Mayadevi temple, which houses many of the brick ruins from a temple from the 3rd century BC, and a marker stone for the Buddha’s birth. Right outside the temple is one of the Asoka pillars, stone pillars of the emperor Asoka, who was responsible for spreading Buddhism across his empire some centuries after the Buddha’s death. The end of the inscription, which says that the king had visited in the twentieth year of his reign and worshiped the marker stone, mentioned that ‘the Lord having been born here, the tax of the Lumbini village was reduced to one-eighth.’ In some ways, I thought, things haven’t changed all that much – the dharma and worldly matters have always been intertwined.”