This past December, Alvira Tyagi ’25 set off for Bengaluru, India for three weeks of service in the public healthcare sector. She was awarded a Mittal Institute student grant to intern at the non-profit organization, Society for Community Health Awareness, Research, and Action (SOCHARA), an organization dedicated to community health. Alvira set off to better understand what successful community health action looks like in the context of the social determinants of health, particularly in culturally and socioeconomically diverse nations like India.

The Mittal Institute application for winter grants is now open! If you’re a current Harvard student in a degree-program at Harvard (undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral degree candidates are all eligible!) interested in a South Asian research project, internship, or language study program, apply by October 13.

“At the beginning of my second year at Harvard, I found myself at a crossroads. As a double concentrator in Neuroscience and Government, I am truly captivated by medicine’s intersection with policy and politics. Accordingly, as an aspiring physician, I yearn to understand my patient’s medical conditions within the context of the sociopolitical factors that influence their access to healthcare resources in the first place. Striving toward global health equity was certainly a topic of fascination for me in the classroom — yet I grew fervently eager to examine public health in a more direct field visit setting, where I could interact directly with residents and dissect the community’s existing barriers to good health.

So, I decided to use my winter break to undertake an internship in Bengaluru, India with SOCHARA, an organization that flips the top-down vision of global health upside down and approaches healthcare disparities by deploying community health workers and programs at the ground community level. Through initial conversations with the organization’s staff prior to my internship, I was inspired by their rooted vision in meeting people where they are, by working from the grassroots community stance to inform and empower individuals about their wellbeing. SOCHARA conducts community health research to clearly identify the needs of individual communities and correspondingly plans initiatives within underserved villages in the Karnataka state and beyond. These initiatives include hygiene campaigns, maternal and menstrual health modules, and general health-related informative discussions and resource sharing, among others.

On my first day of the internship, I was warmly welcomed by the SOCHARA staff and beckoned into the organization’s library, a mesmerizing array of bookcases containing literature, data, reports, and videos on the status of global, national, and local health outcomes over the past few decades. I became engrossed in several books and simultaneously chatted with SOCHARA staff about their wealth of community and public health knowledge, which guided my foundational grasp of the organization’s goals throughout the course of my internship.

Harvard undergrad Alvira Tyagi (left) with her mentor, Janelle, at the entrance of SOCHARA.

The library also equipped me to comprehend Indian healthcare in its physical form as a multi-payer universal medical care system with the three distinct layers, the primary, secondary, and tertiary stages. At the primary level are primary health centers (PHCs) and sub-health centers (SHCs) which are state-owned and provide typical checkups and appointments in a non-specialized sense. The secondary tier includes community health centers (CHCs) which are meant to provide referral care from PHCs with an increasingly specialized focus. CHCs are often driven by non-profit or private organizations that aim to address the needs of consumers in individual communities. The most specialized care is addressed at the tertiary level, where medical colleges and district hospitals serve patients who have the most pressing and precise healthcare needs.

As I continued my exploration of the organization’s breadth of illuminating resources, I watched impactful videos about community health impacts from historical national crises, most significantly the Endosulfan spraying devastation that began in the 1970s. I learned of the commercial endosulfan pesticide spraying throughout cashew plantations in southern India, which occurred in close proximity to villages of homes and resulted in abnormal health conditions across the residential population. As a neuroscience student, I was keenly aware of the detrimental effects of the diseases and congenital abnormalities discussed as side effects of the endosulfan spraying in the video, including physical and mental disabilities, cancer, and psychiatric disturbances. This gut-wrenching video imparted a deeper sense of the value behind empowering communities to provide a countervailing force against unjust practices that restrain their well-being.

After ensuring a solid foundation in the historical context of SOCHARA’s mission, I was ardent to start field visits, an experiential learning process that would yield direct perspective on the issue of community health. Thus, I knew that SOCHARA’s field visits would provide me with a unique opportunity to understand communities as they are, and not just as I believed them to be. Given my fluency in Hindi, I was enthusiastic to hear directly from community residents about subjects ranging from maternal and menstrual health to vaccination access during the pandemic. I was grateful for the chance to join the SOCHARA team on four total field visits, two of which were to the village of Maya Bazar and the other two to Anandapuram.

It was salient for me to approach these visits with a toolkit of skills to help guide my observations and learnings in the field. SOCHARA’s “Capacity Building for Health Equity in India” instructional handbook provided a comprehensive checklist of items to consider when entering a community. I learned to pay attention to an assortment of sociocultural factors, including the community’s existing infrastructure, settlement patterns, demographics, informal and formal leaders, culture, existing groups and organizations, and present-day institutions.

Two of my direct field visits were to Maya Bazar, an impoverished village that has existed for nearly 150 years with origins dating to the British Empire. Visiting Maya Bazar was an astonishing experience which enabled me to witness firsthand that community health is not necessarily centered around addressing gaps in wealth, but rather, differences in priorities.

As I spoke to people around the Maya Bazar community, many residents carried cellular devices, but very few had access to private household toilets. Although Maya Bazar is a low-income village, this does not necessarily imply that everyone residing there is completely poverty-stricken. There may simply be a difference in prioritization of needs – iPhones may come before sanitation in several of these households, as these devices are integral for business, communication, and receiving a steady income to support one’s family.

This observation demonstrated a misconception of mine, and I was grateful to gain a novel viewpoint here that was different from the belief I previously carried.

Walking through the narrow passages in Maya Bazar.

I was also so overwhelmed by the kindness I received during my visit to Maya Bazar. As an unfamiliar face in such a close-knit community, I did not expect to be treated with as much openness and warmth as I received. Even in an incredibly diverse nation like America, there persist many issues with foreigners being viewed with racism, discrimination, and hostility. In Maya Bazar, however, many families cordially invited me into their homes for tea and lunch. Multiple elderly residents were generous enough to give me a few minutes of their time and answer my questions about their access to healthcare, even amidst grueling ailments. I felt so welcomed by the people of Maya Bazar and I will never forget that compassionate sentiment.

Attending a meeting with community residents and SOCHARA staff in Maya Bazar.

Next, I undertook field visits to Anandapuram, a larger community with 900 households involved in occupations such as the selling of vegetables, bookbinding, painting, gardening, driving, and carpentry. There, I led focus group discussions on menstrual and maternal health awareness, as SOCHARA had recently delivered a series of hygiene modules to inform members of the community about recommendations and products for taking care of women’s health.

What struck me the most from the focus group discussions was the overwhelmingly positive feedback from the residents about how successful SOCHARA’s women’s hygiene programs were. The women I spoke with cited the beneficial information they learned, how they altered their current health practices, and mentioned that they even passed this knowledge on to younger women in the community. I was intrigued to learn about the stigmas surrounding menstrual hygiene in the community and was optimistic to hear that many of those biases were enervated after the instructional sessions. It was astonishing to see and hear the everlasting impact the modules had — and this was another example of the direct community empowerment that is so vital in ensuring an effective community health approach.

Leading a focus group discussion on women’s health with residents of Anandapuram.

Discussing the positive effects of the women’s hygiene modules with Anandapuram’s gynecologist.

As I write this, I am amazed by how fast time has flown and it is quite bittersweet to reflect on this after such an enlightening experience at SOCHARA — I truly miss it. Although I have many takeaways from my internship in India, I will mention two key ones here that will certainly remain with me for the rest of my life.

Firstly, the community health approach is actionable, implementable, and impactful. I had never worked to support healthcare equity through this community-driven effort before, so I was quite intrigued to see if I would find the effects of this more unique approach beneficial. Particularly after my field visits, I can assuredly say that community health is a highly inclusive manner of meeting and addressing the needs of people while preserving their autonomy and dignity.

A selfie with Dr. Thelma Narayan, the founder and director of SOCHARA.

Secondly, the bottom-up community health approach, although very impactful, demands immense hard work and effort. SOCHARA has invested years into Maya Bazar and Anandapuram. The volunteers directly on site pour their passion and vitality into these communities for days on end, and the community responds with the time and patience to fully engage with SOCHARA’s efforts in order to make change a reality. Community health work is not easy; in fact, it can be very frustrating and painstaking at times. Regardless, once we are willing to put in this valuable work more broadly and maximize impact, community health is instrumental in connecting residents with the tools needed to empower them in their well-being.

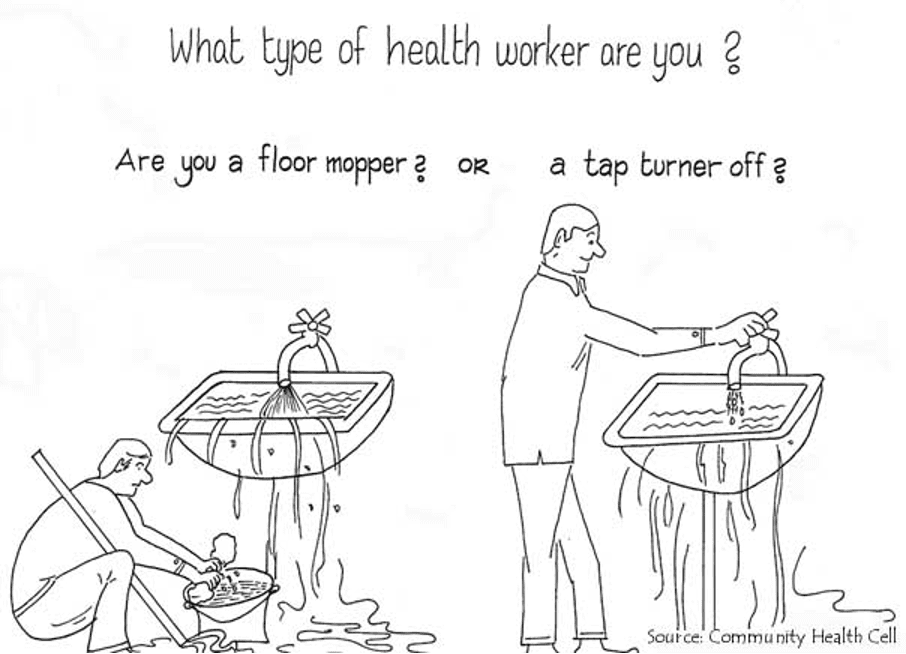

I will end my reflection with the graphic at right, which encapsulates a key take-home message from my SOCHARA internship. I saw this cartoon in the library on my first day at SOCHARA, and it galvanized me to envision the type of physician and policymaker I aspire to become in the future. I am committed to this paradigm of community health, and I aim to stay ahead of health crises rather than “mop the floor” after problems arise with devastating consequences. This constant push toward being a well-informed, thoughtful, and inclusive community health practitioner is a goal that will perpetually remain at the forefront of my career ambitions.

Source: Community Health Cell, SOCHARA.

I would like to wholeheartedly thank the Mittal Institute for providing the funding to undertake this insightful and transformative internship in India. Coming back to my birth city of Bengaluru was incredibly sentimental and I am grateful to have returned to the United States with a clearer vision of the physician, student, and woman I aspire to be.