Dr. P. Sivakami, an acclaimed Indian author who predominately writes in Tamil across many genres of literature, recently spoke at Harvard in conversation with Professor Martha Selby, Sangam Professor of South Asian Studies and Professor of Comparative Literature Harvard University. P. Sivakami began her career as an Indian Administrative Services officer and later became an author of six novels, four collections of short stories, and many essays and other works of non-fiction. Her first book, Pazhiyana Kazhidalum, was the first novel in Tamil to be authored by a Dalit woman. We spoke with Dr. Sivakami about her career as an author, governmental official, and politician.

Mittal Institute: Dr. Sivakami, your first began your career as an IAS officer. What drew you to governmental work, and what were some highlights of your career?

Dr. P. Sivakami: I come from Perambalur, a small town in Tamil Nadu, which recently attained the status of a district headquarters. My primary schooling was in a government run Adi-Dravidar welfare school, meant for Dalits and tribes. Later, I was moved to a private missionary school called St. Dominic’s Girls’ High School. I was a topper, school athlete and the school pupil leader at one point of time. I won prizes in essay and oratorical contests at the inter-school and inter-collegiate competitions. I was also equally interested in extra-curricular activities.

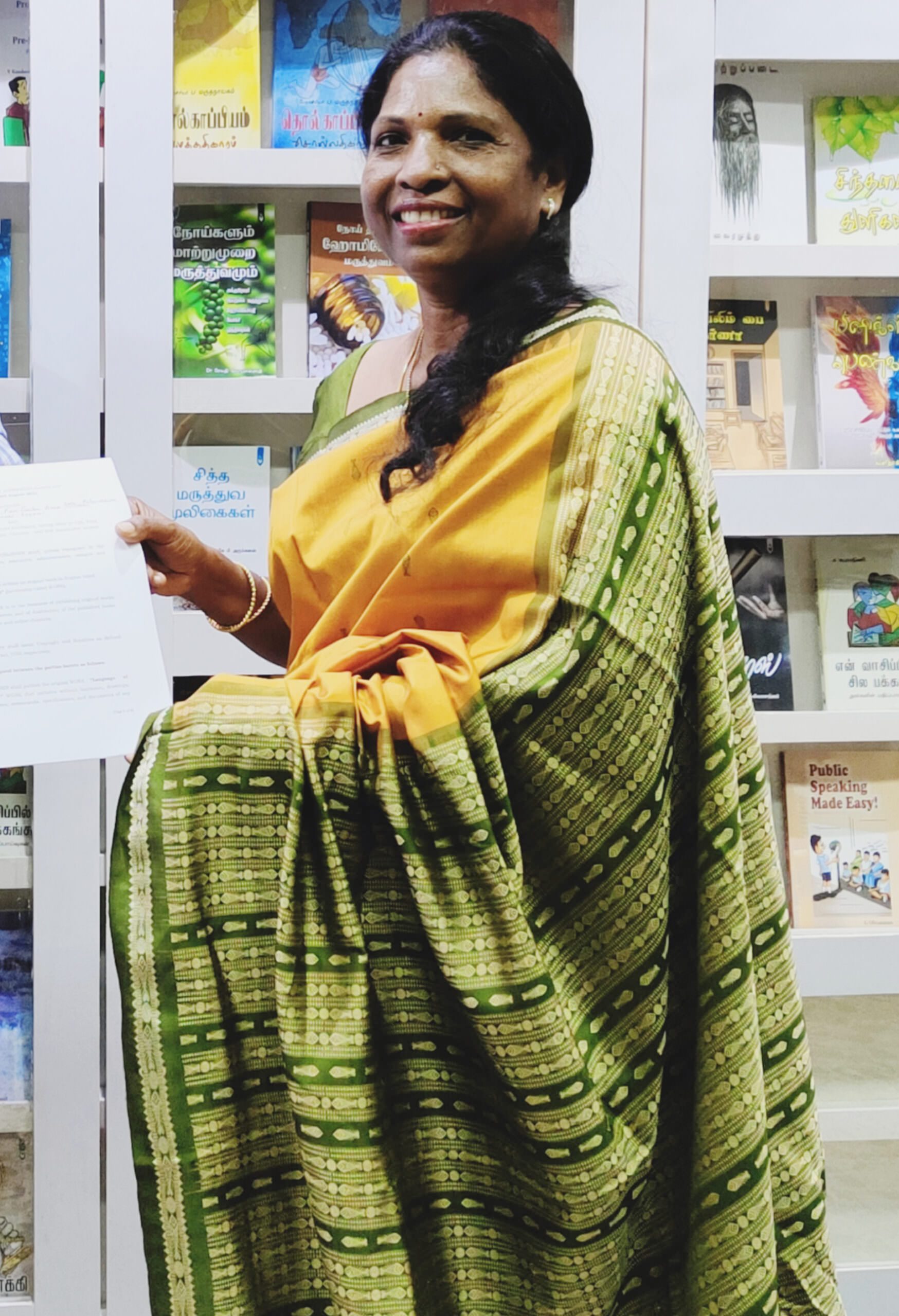

Dr. P. Sivakami.

During my bachelor’s degree, placed first in the state for Part 1 Tamil subject, and was awarded Sundarammal Tamil Prize and Jawaharlal Nehru memorial award. In graduate school, I passed with distinction and won the Sudarsan Gold Medal. I was the teacher’s pet at school and college and received their guidance and support throughout. Though I did well in school and college, I secretly nurtured a dream of becoming a writer since the day my story was selected in a short story writing competition conducted for college students by a popular Tamil magazine in 1975. And also, I was selected for a course on creative literature in 1976 along with twenty other girls and boys from colleges all over the state.

However, my father, an ex-member of the legislative assembly, having had association with the officers of the Indian Administrative Service during his tenure as MLA, wanted me to appear for the UPSC (Union Public Service Commission) examinations. As per his direction, I appeared for the competitive examination and entered the coveted administrative services. In short, my strong academic background, combined with my other skills and my father’s dream helped me to become member of the service. In the service my longest innings were in tourism department with government of Tamil Nadu as well as with Government of India. I could proudly say that I turned the corner for Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation by making profit and earning foreign exchange which hitherto had been incurring loss. As a result, I was posted as Regional Director East Asia for Government of India Tourism based at Tokyo, Japan. I was instrumental in abolition of child labour. In the capacity of Additional Secretary labour and under the guidance of Secretary labour Mr. P.Shankar IAS, I toured seven districts where children under the age of fourteen were employed in match and fireworks industries and prepared a report and based on that report the project for abolition of child labour was sanctioned. And when I was the Commissioner of Employment Training, I organized a number of employment camps in schools and colleges linking the industries and job seekers. The model I developed was later adopted by politicians as one of their pet schemes. In short, wherever I was posted, I discharged my duties with utmost efficiency and earned the good will of my bosses and appreciation from the public.

Mittal Institute: You founded your own political party, Samuga Samathuva Padai, in 2009. Can you share with us some principles of the party? Why did you decide to transition from IAS officer to politics?

Dr. P. Sivakami: Though I liked the importance attached to the service and the exposure I gained, I started feeling the pressure of political domination in day today administration as well as in deciding the career paths of officers like me. I was not the only one to complain about it, but it was the general gossip in the officers’ lunch room. In the 1990s I started editing and publishing a subaltern literary magazine named Pudhiya Kodangi (Kodangi is the name of a musical instrument mainly used to drive away the evil spirits). The magazine published the creative work of Dalits and other oppressed caste, i.e., OBC and Bahujan writers, who otherwise were unable to get their work published. Pudhiya Kodangi nurtured the record growth of more than hundred writers as the magazine itself grew over a period of 28 years. My interest slowly drifted from literature to the living characters/human subjects of my fictions and essays, namely the subaltern women, Dalits, tribals and the transgendered communities.

My interest slowly drifted from literature to the living characters/human subjects of my fictions and essays, namely the subaltern women, Dalits, tribals and the transgendered communities.

At that point, there was an opportunity to serve those sections directly as Secretary to Government of Tamil Nadu, Adi-Dravidar Welfare Department. I hardly realized that it was going to be a turning point in my life. It was like bearding the lion in its den! I discovered that the entire gambit of government had been designed in such a way that there is no salvation for Adi Dravidars for many years to come unless the heads of states and the central government make policies in their favour. Since I had already written a novel on this subject and I am translating it to English, I prefer not to divulge the details now. When I realized that my efforts should be oriented towards helping/compelling the governments to draft effective transfer policies for the poor and under privileged sections of our society, I thought that as an insider, the chances of driving home my ideas were remote, because there were key players among the IAS officers who had directly or indirectly identified themselves with powerful politicians and there was no option left to me but to work as an outsider. I had resorted to activism, like a character in my novel, and that I considered as being truthful both to me and to my writing.

My creative writing had taken on a different direction, and I began to draft and develop actionable plans in the form of leaflets and pamphlets. I wrote at length on Dalit Land Rights and Tribal Land Rights. I printed five thousand copies and distributed them for free. I founded the ‘Dalit Land Right Movement’ and the ‘Women’s Front’ and visited as many villages as possible in an effort to create awareness among people. Because of my efforts in mobilizing people towards their legal and human rights, the Tamil Nadu Government announced a scheme of free distribution of land to an extent of two acres to the landless poor in 2006. After ‘Women’s Front’ had collected over 250,000 women for its conference under the title “Women and Politics” in February 2007, all political parties felt compelled to start organizing seminars/rallies in an effort to keep their women cadre intact. In 2008, I organized a conference for Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes Employees in government bringing their long pending grievances to the attention of the government. Nearly 20,000 employees attended it. And I thought that it was high time to quit the service and work from a different platform. I founded the political party by name ‘Samuga Samatuva Padai’ (Party for Social Equality) in December 2009. The name of the party is not only a literal translation of ‘Samta Sainik Dal’, a movement begun by Dr.B.R.Ambedkar, but also resonates with his thoughts and writings. In my opinion, all conceptual frameworks, namely the ideologies, could be transformed into capillary functions. Hence Samuga Samatuva Padai started addressing those life changing issues. Poverty could be alleviated almost permanently only by distributing a small extent of land to the landless agricultural labourers as they are a major constituent of people below poverty line. Land to the landless, home to the homeless, one primary school in each Dalit and Tribal habitation, imparting employable skills to the jobless, political quota of 50% for women, effective implementation of Protection of Civil Rights Act and laws pertaining to women’s rights, a work shed in each village exclusively for women to augment women’s participation in the labour force, medical/ health care centers for senior citizens, especially women in each block (a block consists of roughly 100,000 population) are some of the goals that the party aims at.

P. Sivakami at a book signing.

Mittal Institute: Let’s talk about your acclaimed writing career. You are the first Dalit woman to become a Tamil novelist, after publishing Pazhayana Kazhidalum, translated by yourself to The Grip of Change. The book “takes on the patriarchy” of the Dalit movement. What led you to write this book, and how factual was it?

Dr. P. Sivakami: The first ever short story by me was written at the request of my Tamil teacher when I was in 10th grade in school and the same was published in a Christian magazine by name ‘Thennoli’ circulated locally. This encouraged me to participate in short story writing competition later. The responses received from readers for my prize-winning short story were varied, and made me to think deeper as they raised questions on my social responsibilities and ideological perspectives. For a short duration, I was in the SFI (Student federation of India), the student wing of the communist party. Later I met few academicians who were critical of the communists’ approach to caste and the so-called untouchables. Their arguments had considerable impact on me.

Though my first novel was in a simple narrative form, it is complicated because the subject matter was caste. I had seen many victims of caste atrocities, and also witnessed the perpetrators of such atrocities being let off scot-free. I wanted to capture those nuances in my novel. Moreover, in the eighties not many writers had attempted to choose caste as a theme. Two men writers belonging to Dalit community tried to portray the life of Dalits in their novels, although they were reluctant to reveal their identity as well as their characters’ caste identity due to reasons best known to them. To problematize caste wasn’t easy for me either. But I was strongly convinced that initiating an open dialogue through literature was the need of the day. In annihilation of caste, I believe that the first step is, accepting its omnipresence, and subjecting it to a dialogue on epistemological and ontological grounds. Because the very word ‘Paraiyah’ by a Dalit invokes mixed feeling of disgust, shame and guilt in others. The novel was a big blow on the caste conscious literary figures who hitherto preserved the purity of literature by not discussing caste in their texts. My work set in motion an open dialogue about caste and the problems of untouchability in literature.

My work set in motion an open dialogue about caste and the problems of untouchability in literature.

The novel, from the perception of Dalits and Dalit women towards social and class hierarchy, reveals how caste and patriarchy collude to govern the pattern of land ownership, and control the village economy in India. Your question wants me to clarify why I had targeted Dalit patriarchy in my novel. The answer is simple. Caste and Gender are inextricably related to each other. By controlling women’s bodies, the caste system was maintained and safeguarded throughout. In whichever way dominance operates, I feel it should be opposed.

Mittal Institute: What are you most proud of with the novel?

Dr. P. Sivakami: As I had already mentioned, all that I can claim is that caste has become a subject matter of discussion in literature. As an activist, in all rights-based activities, I have played my role and continue to contribute. My subsequent novels “The Taming Women” and “The Cross Section”, published by Penguin and Sahitya Akademi respectively, have carved distinct places for themselves in Tamil Feminist writings.

Mittal Institute: You are an activist and endeavor to lend a voice to the voiceless. Can you talk about some causes you have championed?

Dr. P. Sivakami: As an activist I have been editing Pudhiya Kodangi monthly magazine for past 27 years, a record-breaking achievement in recent Tamil history. This magazine plays a role of training the trainers on Ambedkar’s ideology of democracy. Advocacy on land rights has resulted in certain positive impacts on the government, and the announcements from Tamil Nadu government relating to distribution of land to the poor and appointment of a commission to retrieve Panchami lands illegally occupied by others are the resultant effects. The “Forum for Indian Women Intellect”, which I founded in 2018, conducts surveys on many important areas of neglect, for example a survey about increased c-section operations among poor and downtrodden women in the rural areas, school drop outs in remote areas are few of them. The forum follows up its survey reports with appropriate authorities for remedial actions.

P. Sivakami joins tea estate workers in their campaign for better wages and housing at Coonoor, Tamil Nadu.

Mittal Institute: How has being a Dalit woman influenced your writing and career? And have you seen any growth or change in the attitude of society over the years?

Dr. P. Sivakami: Transcending the boundaries of birth identities like caste, gender, race and religion is not easy, although it is still possible with self earned and progressive identities to have an objective outlook towards life and matters governing it. That gives a hope to people who are in the process of creating a better world. Though I am a Dalit and woman, I wish to initiate changes for the betterment of everyone, and hence I start with critiquing the self and move on to the basic structures of the caste ridden society. My work of art is open to all for reading or learning, although I consider it very important that people relating to the subject matter should read it for the reason that the change in them will necessitate change in others. The ‘Others’ have to face the changed identities, identities who are no longer ashamed of others’ sins, no longer the feudal slaves, the neo-Dalits or the enlightened persons who are not limited by caste or gender. To me it appears that my works are like instruments of change in a very small way.

Though I am a Dalit and woman, I wish to initiate changes for the betterment of everyone, and hence I start with critiquing the self and move on to the basic structures of the caste ridden society.

Mittal Institute: What is next for you with your work?

Dr. P. Sivakami: I am currently working on a Tamil novel portraying women of different streams, and also transcreating another one based on my Tamil novel which portrays how discrimination operates within the Indian bureaucracy.