The Mittal Institute’s Syed Babar Ali Fellow, Muhammad Imran Mehsud comes to Cambridge from Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan, where he is an Assistant Professor of International Relations. He is an expert on South Asian transboundary hydropolitics and his research project at the Mittal Institute examines the effectiveness of the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960 in settling contemporary transboundary water issues between India and Pakistan. We spoke with Imran about his research and his plans for his time at Harvard.

Mittal Institute: Welcome, Imran! What drew you to study India-Pakistan water relations, and what particularly captivates you about the Indus?

Muhammad Imran Mehsud: Thank you for inviting me to this interview. My engagement with India-Pakistan water disputes began in 2010 while pursuing my MPhil at Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad. My thesis titled ‘Hydropolitics in South Asia: A Case Study of India-Pakistan Water Disputes’ delved into the complex transboundary water dynamics in a region where historical water disputes have been exacerbated by recent climatic changes. Recognizing the critical role of water in the agrarian economies of India and Pakistan, and the Indus basin’s exposure to climatic and demographic shifts, I realized the escalating significance of water disputes between the two states.

![Pic 1[79] copy](https://mittalsouthasiainstitute.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Pic-179-copy.jpg)

Muhammad Imran Mehsud.

Continuing this trajectory, my doctoral thesis, ‘The Indus Waters Treaty: Pakistan’s Quest for Water Security,’ examined the treaty’s role in navigating these challenges. The Indus River, beyond its economic importance, is woven into the fabric of regional history, literature, and culture. Particularly for Pakistan, the Indus is a cornerstone of both its agrarian economy and its national identity. Unfortunately, climate change’s impact on the Himalayan glaciers threatens not only the river’s vitality but also the livelihoods of millions reliant on it.

Particularly for Pakistan, the Indus is a cornerstone of both its agrarian economy and its national identity. Unfortunately, climate change’s impact on the Himalayan glaciers threatens not only the river’s vitality but also the livelihoods of millions reliant on it.

Mittal Institute: Can you talk about the 1960 treaty, and how this has affected water rights and obligations for each country?

Muhammad Imran Mehsud: The division of the Indian subcontinent by the departing British left a complex legacy, including the initiation of a water dispute between India and Pakistan. Both states initially sought to resolve this dispute through bilateral negotiations, but a permanent agreement was not reached until the World Bank intervened in 1951. The Bank’s intervention set in motion a series of detailed negotiations over the course of nine years, culminating in the signing of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in 1960 by India and Pakistan, with the World Bank also signing the treaty for certain specific provisions.

The success of these negotiations is often attributed to various factors, such as the accommodating policies of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, the pragmatic leadership of Pakistan’s then-President General Ayub Khan, and the need for water and finances for agricultural development in both states. However, my research highlights that the shifting geopolitical dynamics of the Cold War in South Asia, especially after China’s adoption of communism, played a significant role. The West, particularly the United States, aimed to prevent the Kashmir dispute, which is intrinsically linked with the Indus water dispute due to the strategic flow of the rivers through the region, from developing into a larger conflict reminiscent of the Korean War, thereby seeking to mitigate any opportunity for Soviet involvement in the region.

The IWT defined the rights to the six rivers of the Indus basin, apportioning India the waters of the three eastern rivers and assigning Pakistan the waters of the three western rivers, the latter carrying 80 percent of the water flow of the basin. The treaty successfully resolved the historical transboundary water dispute. Nevertheless, it also provided India with limited rights over the western rivers that flow into downstream Pakistan, rights that were not part of the initial discussions as reflected by the World Bank’s 1954 proposal. Political instability in Pakistan, with its frequent changes in leadership, resulted in the state’s inability to sign the Bank’s initial proposal. When General Ayub Khan assumed power, his administration’s hastiness led to an agreement that led to the inclusion of these Indian rights in the IWT. These limited Indian rights serve as the main source of contention in the ongoing water disputes between India and Pakistan.

![Pic 2.[68]](https://mittalsouthasiainstitute.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Pic-2.68.jpg)

Muhammad Imran Mehsud along the bank of the Indus (Tha Kot, Northern Pakistan).

Mittal Institute: How have relations between the countries changed over the years, in respect to water?

Muhammad Imran Mehsud: The IWT functioned smoothly for the first forty years of its installment, successfully managing the water relations between the two riparian states and garnering accolades from a multitude of hydropolitical scholars. However, the evolving climatic, hydrographic, and demographic challenges began to test the treaty’s resilience. With India initiating the utilization of its rights over the western rivers to support its burgeoning population’s demands, the IWT started to encounter difficulties. India’s plans and subsequent construction of numerous hydroelectric projects on these rivers led Pakistan to fear for its downstream hydrological and strategic security, prompting it to repeatedly accuse these projects of violating the treaty. Pakistan’s accusations were addressed through different dispute resolution mechanisms provided by the IWT. However, the India-Pakistan water conflict recently became more intricate as each state began to favor different resolution mechanisms outlined in the IWT, each advocating for the method that seemed to advantage their respective positions.

Mittal Institute: What is your research project that you intend to explore while here in residence?

Muhammad Imran Mehsud: At the Mittal Institute, my research focuses on examining the effectiveness of the IWT in managing transboundary water issues between India and Pakistan. The IWT incorporates two dispute resolution mechanisms: the Neutral Expert (NE) and the Court of Arbitration (CoA). The NE mechanism was first invoked when Pakistan raised objections to India’s construction of the Baglihar Hydroelectric project on one of the western rivers, with the NE’s decision in 2007 favoring India. Conversely, the CoA was first employed when Pakistan objected to the Kishanganga hydroelectric project on another of the western rivers, resulting in a verdict in 2013 that largely favored Pakistan.

Recently, with Pakistan’s objections to India’s Ratle hydroelectric project and queries regarding India’s compliance with the design of the Kishanganga project, a preference has emerged for the CoA mechanism from Pakistan, while India continues to advocate for the NE process. The World Bank’s unprecedented step of simultaneously invoking both mechanisms presents new complexities and tests the robustness of the IWT. My research, therefore, intends to explore these emerging challenges, particularly how the IWT stands up to the divergent preferences in dispute resolution mechanisms, against the backdrop of the latest shifts in the water dispute dynamics between the two states.

Mittal Institute: You grew up in Waziristan on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border and are now at Harvard, can you describe your academic journey?

Muhammad Imran Mehsud: My academic journey began in the government-run schools of Waziristan, a place marked by its peripheral, traditional character and notably low literacy rates. Our school was limited to a single room, repurposed by the teachers as a staff room. As a result, we held our classes outdoors, sitting on the ground beneath cedar, olive, or chinar trees—distinct boundaries without the confines of a traditional classroom. Thus, we had a ‘class’ in essence but not a ‘room’ in form. None of my early classmates pursued education beyond our humble beginnings. However, I seized the opportunity to attend a more established school outside Waziristan, eventually making my way to one of the best universities in Pakistan. From there, I earned a chance to study at the University of Cambridge through a six-month doctoral fellowship, leading to my current role as a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard.

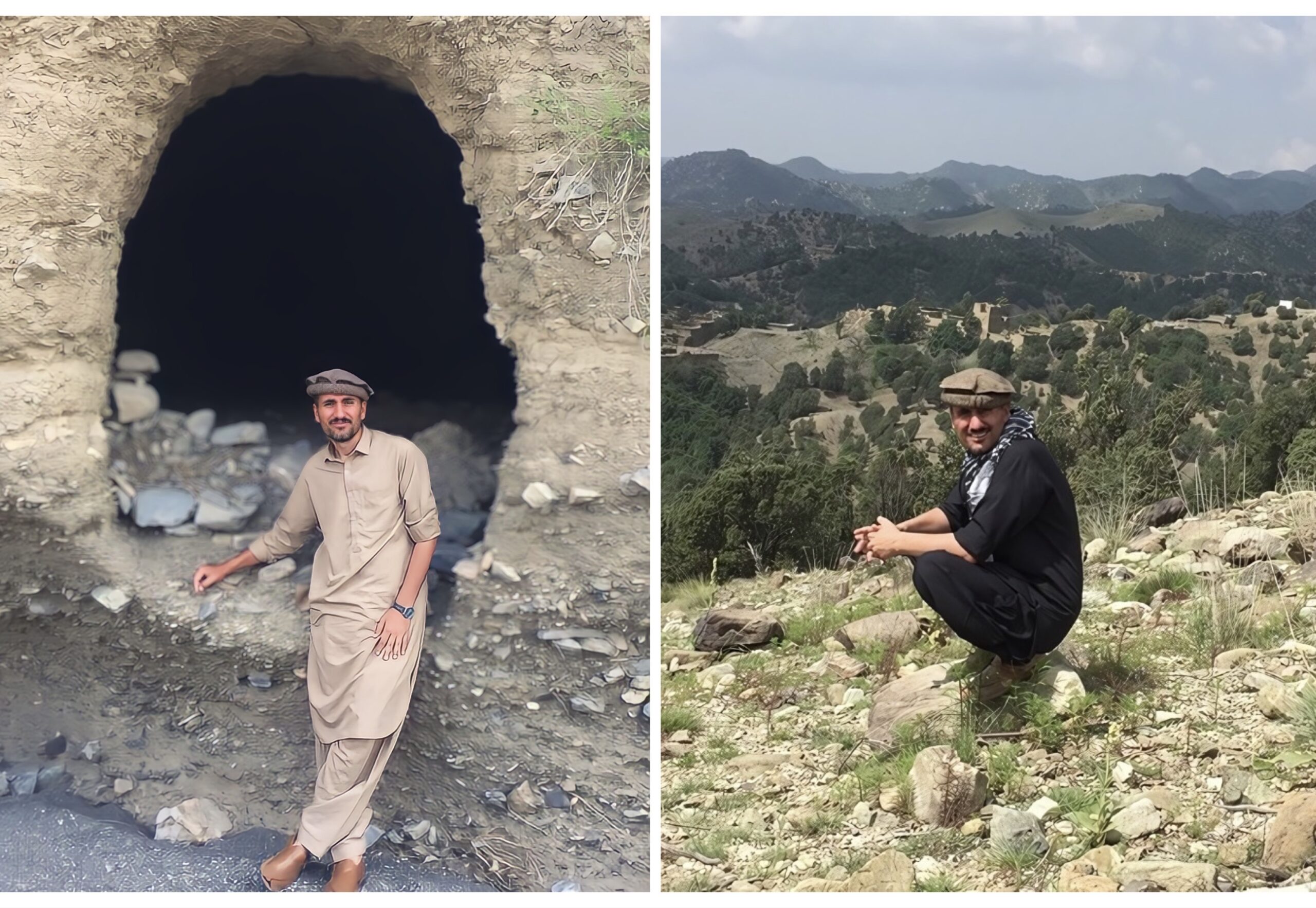

Image, left: The caves of Waziristan: These countless caves served Imran’s tribe as winter homes and strategic outposts against past colonial incursions; Image, right: In the serene mountains of Waziristan.

I have found that universities in the developed world offer a wealth of opportunities for study, research, and other scholarly activities. The main challenge for students and researchers from regions like mine lies in our perception; there’s a prevalent belief that such opportunities are beyond our grasp, deterring us from even attempting to capitalize on them. It’s this mindset that often holds us back from taking the initiative to embrace these opportunities and explore the avenues that could lead to academic and professional growth.

Mittal Institute: Can you share a bit about your forthcoming novel, based on “unlearning” childhood lessons?

Muhammad Imran Mehsud: The inspiration for my novel came from a childhood memory during the final stages of the Soviet-Afghan war. As a five-year-old in Waziristan, my cousin and I would only kill red ants, equating them with Russian communists, while sparing the black ones. Decades later, while doing my doctoral research at Cambridge, the prospect of living with a Russian roommate unearthed uncomfortable feelings, prompting me to trace these biases back to my early years. I realized that biases formed in childhood lingered subconsciously. This realization became the seed for my novel, which explores the profound impact of childhood indoctrinations and the challenging process of unlearning them. Academically, I’ve come to see this unlearning as an essential part of re-educating oneself, stripping away the layers of early political conditioning to embrace a more informed worldview. In a way, my academic journey has been a quest to first recognize these early political lessons, then dismantle them and replace them with the insights gained through higher education.

I realized that biases formed in childhood lingered subconsciously. This realization became the seed for my novel, which explores the profound impact of childhood indoctrinations and the challenging process of unlearning them.

Mittal Institute: What is something that has surprised you about Harvard (or Cambridge) so far? What are you most excited about doing while in the United States?

Muhammad Imran Mehsud: Harvard, known for hosting some of the finest minds in the world, certainly has the potential to surprise. Yet, in the long series of surprises I’ve encountered, I think my time studying at Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad provided the most significant intellectual revelations. It was there that I began to question my previous lessons and political conditioning, largely thanks to a faculty comprised of many who held doctorates from esteemed institutions like Harvard and MIT. As for cultural surprises, living previously in Cambridge, UK, was quite the experience. Being accepted as a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard, given my modest academic beginnings, was also quite unexpected. As these are my early days and I am still settling in, I’m anticipating further surprises at Harvard and Cambridge. Now, while here at Harvard, I plan to participate in various workshops, lectures, seminars, and conferences, in addition to completing my research project. I also aim to find a publisher for my novel.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subjects and do not necessarily reflect the views of LMSAI, its staff, or its steering committee.