The Harvard Buddhist Studies Forum launched its spring semester events series with a February 7 talk by Todd Lewis, Distinguished Professor of Arts and Humanities at the College of the Holy Cross and Research Associate in Harvard’s Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies. His talk, co-sponsored by LMSAI, explored “Reconfiguration and Revival: Newar Buddhist Traditions in the Kathmandu Valley (and Beyond)” – watch the event video here. We spoke with Todd to learn more about the motivations behind his research on South Asian religions, and what society can glean from their teachings.

Mittal Institute: Thank you for the talk, Todd! You have been teaching in Holy Cross’ Religious Studies Department since 1990. Your scholarship has heavily focused on Buddhism in the Kathmandu Valley; in fact, you lived in the Asan Tol neighborhood of Kathmandu for a number of years. What captivates you about Nepal, and what drew you to study Buddhism?

Todd Lewis: As a graduate student at Columbia, with my courses and field exams completed by 1977, I was trying to decide what country and which Buddhist tradition I would study for my Ph.D. research. I wanted to study the least researched Buddhist tradition in the world, and this turned out to be the Newar community in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. The fact that my grad mentor, Theodore Riccardi, was an expert on Nepal also guided my decision.

I have continued to work there for over 40 years now, in large part, because the extraordinary Newar people I befriended in my doctoral fieldwork became some of my closest friends anywhere, and I will always wish to return to Nepal to continue these friendships. I have also been captivated by Newar Buddhist traditions, and the immense professional satisfaction of documenting the wealth of Newar Buddhist narrative texts, religious arts, and ritual traditions. This work in Nepal has more than met my original goal of breaking new ground in studying a little-studied variety of Buddhism. I think that I have also contributed to the development of the field of Buddhist studies by introducing Newar traditions into a larger goal: constructing a greater understanding of Buddhism in history, especially in South Asia. Although Buddhism was built by merchants and thrived in cities across Asia as it spread, my focus on urban Buddhists centered on a merchant community has never been done elsewhere.

![047_13A[62]](https://mittalsouthasiainstitute.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/047_13A62-scaled.jpg)

![IMG_4215 049[41]](https://mittalsouthasiainstitute.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/IMG_4215-04941-scaled.jpg)

Todd Lewis’ scholarship spans more than 40 years. Image, left: Receiving a blessing from Tibetan lama Toton Rinpoche in Kathmandu, 1982; Image, right: Receiving tiki from Lama, 2012.

Mittal Institute: You are the author of numerous journal articles and two books on Newar Buddhism. Can you explain this tradition of Buddhism to our readers – who practices it, and how does it differ from other traditions of Buddhism?

Todd Lewis: These are questions that would require a great deal of time to answer thoroughly! Newar Buddhism is the last surviving tradition of Indic Buddhism that has Sanskrit as its canonical language. It escaped the fate of Buddhism just to the south in the Gangetic plain, where it declined and almost completed disappeared by about 1400CE. It remains one of the most complicated forms of Buddhism anywhere, existing alongside a Hindu majority in a caste-defined society, with a huge textual archive and a very large ritual tradition. Newar Buddhists still live their lives regularly punctuated by the performance of rituals that have their roots in the Indic Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions, most of which may date back seven centuries. Like all Buddhists, Newars honor the Buddha at stūpa shrines and through image rituals; they organize their religious life around making puṇya (“merit”, good karma), including the support of the vajrācārya ritualists affiliated with the local monastic institutions; and those who wish can seek inner spiritual experiences through a variety of meditation practices, from mindfulness cultivation and visualization to forms of tantric praxis. The cultural richness of the urban Newar religious traditions is extraordinary, with Buddhist artisans who are among the most skilled in the world, working in wood carving, stonework, painting, and metal. Newar monastic and family archives have provided most of the Sanskrit texts that scholars have used to understand the history of Buddhist elite thought and ritualism.

Sitting with Nati Bajracharya, poet, activist, and book vendor (left) in his shop, 2012.

Mittal Institute: What are some lessons or guiding principles that society can glean from Newar Buddhism?

Todd Lewis: Newar Buddhists live by following the Buddhist virtue of compassion, and are very generous in providing assistance and hospitality to others. They are very well organized and routinely create social groups to accomplish their goals, whether it is the performance of a specific ritual, do devotional singing, or insure that families suffering a death in their community have a circle of friends to assist in all that goes into arranging for the cremation of the corpse and coping with the first days of mourning. Newar Buddhists practice their faith daily, circumambulating stūpas, making offerings at temples, and meditating. Newar society is one in which the strength of their faith is palpable.

![img071 copy[52]](https://mittalsouthasiainstitute.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/img071-copy52.jpg)

Doing a Puja ritual with Newar Buddhist priest Chini Kaji Vajracarya, 1987.

Mittal Institute: Scholars had predicated Newar Buddhism would “wither away” due to an influence of Hinduism; yet the practice has seen a revival in recent years. Can you share a bit about this evolution, and why there has been a revitalization of the tradition?

Todd Lewis: The answer, and the subject of my talk, explains this more fully than I can here. In my dissertation completed 35 years ago, like most scholars I made a prediction of the slow decline of Newar Buddhism. The main competition was the reformist tradition of Theravāda Buddhism (as found in Sri Lanka, Burma, and Thailand) that was introduced to Nepal over a century ago. But life in Nepal changed in the past three decades. The ten-year Maoist insurrection that led to civil war in 1996 drove the middle class and others living in towns across the Nepal to immigrate into the Kathmandu Valley and nearly quadruple its population. This resulted in Newar landowners seeing the value of their land increase tenfold or more; and this quadrupled the size of the market that Newar merchants had to sell to. As lands were sold and profits increased, this created a new era of prosperity that allowed the Newar merchants and newly-rich to spend part of their largesse on sponsoring the construction of new religious buildings or restore older ones, and to buy new religious icons for their homes. This in turn added orders for art and increased the prosperity of artisans and builders. Newfound leisure also gave many people the free time to pursue more religious activities. Yet another factor was the establishment of a secular national government, ending Hindu dominance. And then there is the role of ethnic and religious pride: with their homeland, the Kathmandu Valley, inundated with over a million people from outside ethnic groups, the Newar Buddhists felt a powerful need to express and celebrate their own identity, so they flocked to join the older religious organizations and sponsor/participate in new devotional activities.

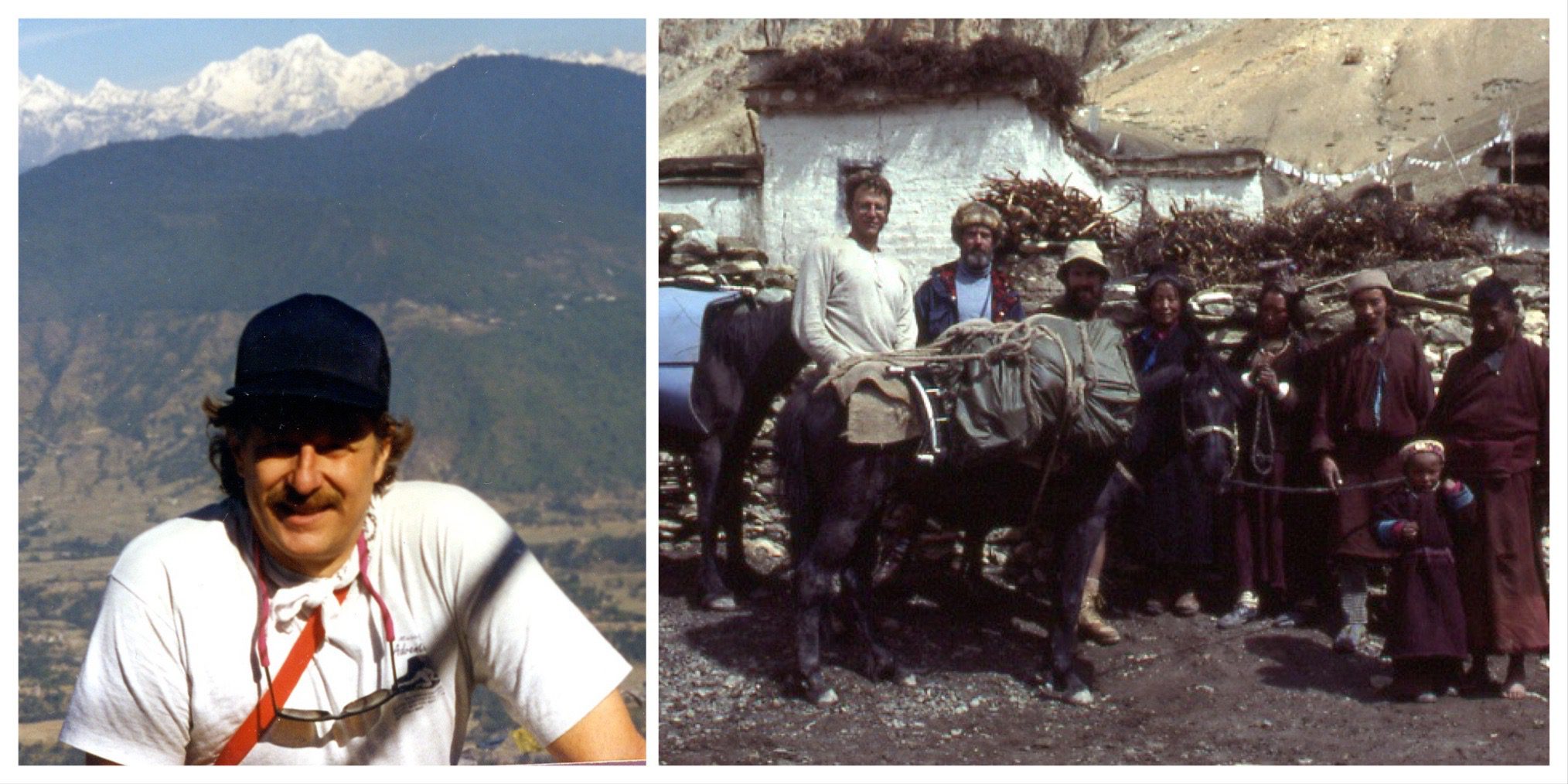

Image, left: Kathmandu Valley with the distant Himalayas, 2012; Visiting Ladakh village, 1980.

Mittal Institute: What is next for your research?

Todd Lewis: I will finally publish my dissertation documenting the urban merchants of Kathmandu (after all these years have passed!) with the addition of a final new chapter that recounts and analyses this renewal of Newar Buddhism, as I have been discussing. I am working on two edited volumes, Buddhism through Material Objects and Gardens and World Religions. I am also hoping to secure funding to document the Newar Buddhist responses to the COVID epidemic: to learn what preventative religious measures were taken and what forms of religious healing rituals were done; and since the epidemic provides a natural experiment, we want to assess how to scale the role of karma belief for Newar Hindus and Buddhists who endured this crisis. There are many texts that describe and analyze the role of karma in human life; this study can assess it actual importance in the religious lives of actual devotees.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subjects and do not necessarily reflect the views of LMSAI, its staff, or its steering committee.