Dr. Bharat Vatwani, one of the speakers at LMSAI’s Annual Cambridge Symposium: Science and Technology – the Future of South Asia, is a psychiatrist based in Mumbai who has dedicated much of his professional career to aiding the mentally ill. Together with his wife, Dr. Smitha, he founded Shraddha Rehabilitation Foundation in 1988, an NGO dedicated to treating mentally ill and unhoused individuals in India. He shared more about his life’s work in the Q&A below, and previewed what attendees can expect at his fireside chat with Prof. Vikram Patel, Harvard Medical School.

Mittal Institute: Dr. Vatwani, can you tell us the story of how you got started in this field nearly 4 decades ago? What drew you to aid those suffering from mental health issues?

Dr. Vatwani: Subconsciously and without even realizing or acknowledging it to myself, because of the loss of a father at an early age and the subsequent hardships, I identify with the down and out in society. I look upon them as brethren, people whose hand I could hold and walk in silent camaraderie. I believe this silent identification ultimately chose to make me come in close emotional contact with the wandering mentally ill roadside destitute.

I remember how I saw a boy of young age scoop canal (nullah) gutter water with his hands, wash his face with it, and then drink it, to moisten his parched throat and quench his thirst.

Dr. Bharat Vatwani | Image from ICA Golden Jubilee Celebrations.

I remember the gaunt, skin-and-bones gold medalist lecturer of the prestigious Sir J. J. College of Architecture, stricken by mental illness, almost dying on the very steps of the equally famous Jehangir Art Gallery, where all the famous and not-so-famous fellow artists would unconsciously walk past him without acknowledging his presence. I remember the lady with schizophrenic catatonic bewilderment on her face, oblivious to the fact that her child had passed away in her arms—the putrid stench of the rotting body causing passersby to hold their nose and avoid her. And I not just identified with these people, but actually acknowledged in pure humility, that there, but for the grace of a God above, go I.

Looking back in reflection, whatever actions of help or succor I initiated for them were too spontaneous and too spinal even for me to understand with pure logic. It was pure connection at the gut level – the unscreamed cry within me reaching out to touch the unscreamed cry within them. And so, it has gone on, for years.

Mittal Institute: So far you have aided more than 7,000 mentally challenged and destitute individuals. A key component of your program is reuniting individuals with their loved ones, post-treatment. Your staff are involved in the entire process, from tracking down the families to arranging for the reunions. Can you describe what a typical care plan at your facility, Shraddha Rehabilitation Foundation, looks like?

Dr. Vatwani: The key to connecting to the mentally ill is empathy: In voice, body language, demeanor, eye contact, and above all, soul contact. Empathy is not sympathy; it is not pity. It is the honest ability to communicate to the man on the streets that “I am you and you are I.” The moment true empathy is established, the claustrophobia of thought, emotions, and actions that were festering within the psyche of the destitute yields like a pricked balloon. The destitute agrees to come with the Shraddha team social worker or to get into the ambulance of our NGO.

The key to connecting to the mentally ill is empathy: In voice, body language, demeanor, eye contact, and above all, soul contact.

There, fresh clothes are provided, the jungle of matted hair cropped and trimmed, any facial hair trimmed. The acceptance of the destitute as human by the Shraddha staff makes them accept themselves as humans. The patients are asked in gentle soothing tones about their names and their histories. Questions no one had ever asked them before, and questions the answers to which they had almost forgotten themselves. This it to remind them that they have an identity and that they belong. Simple questions, no rocket science, but interpersonal rapport at an empathetic level.

The patient is pushed gently to join group activities like yoga or physical exercises in open environments and group prayer meetings in a multi-cultural setting. Coming to know of their specific skills, the patient is often incorporated in gardening, farming, masonry, electrical repair work, cattle attending, cooking, vegetable cutting and general cleaning within the premises. The destitute is made to believe that their contributions are unique, one of its kind, valuable and will be cherished, even after they have gone from the center.

Lastly comes the planning of the Shraddha reunion trips – the trip back to their homeland. It is something that each of the recovered destitute anticipates with bated breath. They know that on a daily basis, an average 2-3 patients receive an okay from the doctor to leave the rehabilitation center. They have understood that their turn too, shall come. Hope rekindled in a lost soul. And loved ones, lost to the passage of time and forgotten because of the blunting of emotional faculties by the onslaught of mental illness, are often remembered with fervor and passion. The atmosphere of men and women remembering their children and wondering how their loved ones and dependents must be faring in their absence, makes every one of them bonded in kindred spirit. Ultimately, during reunions itself, there is an outpouring of emotional catharsis, as loved ones meet loved ones, after perhaps months, years, and decades of separation.

It is not just that Shraddha reunites an individual with their family. In the broader spectrum of events, it is the debunking of the stigma that surrounds mental illness at the individual level, at the family level, and at the society level that Shraddha accomplishes, albeit in bits and pieces, in a fragmented journey across the length and breadth of India. It does this with an all-pervasive compassion and empathy for the plight of the common, grossly misunderstood mentally ill person. And this empathy kindles further empathy for the mentally ill, within the sufferers themselves, their families, their villages and the surrounding societies at large.

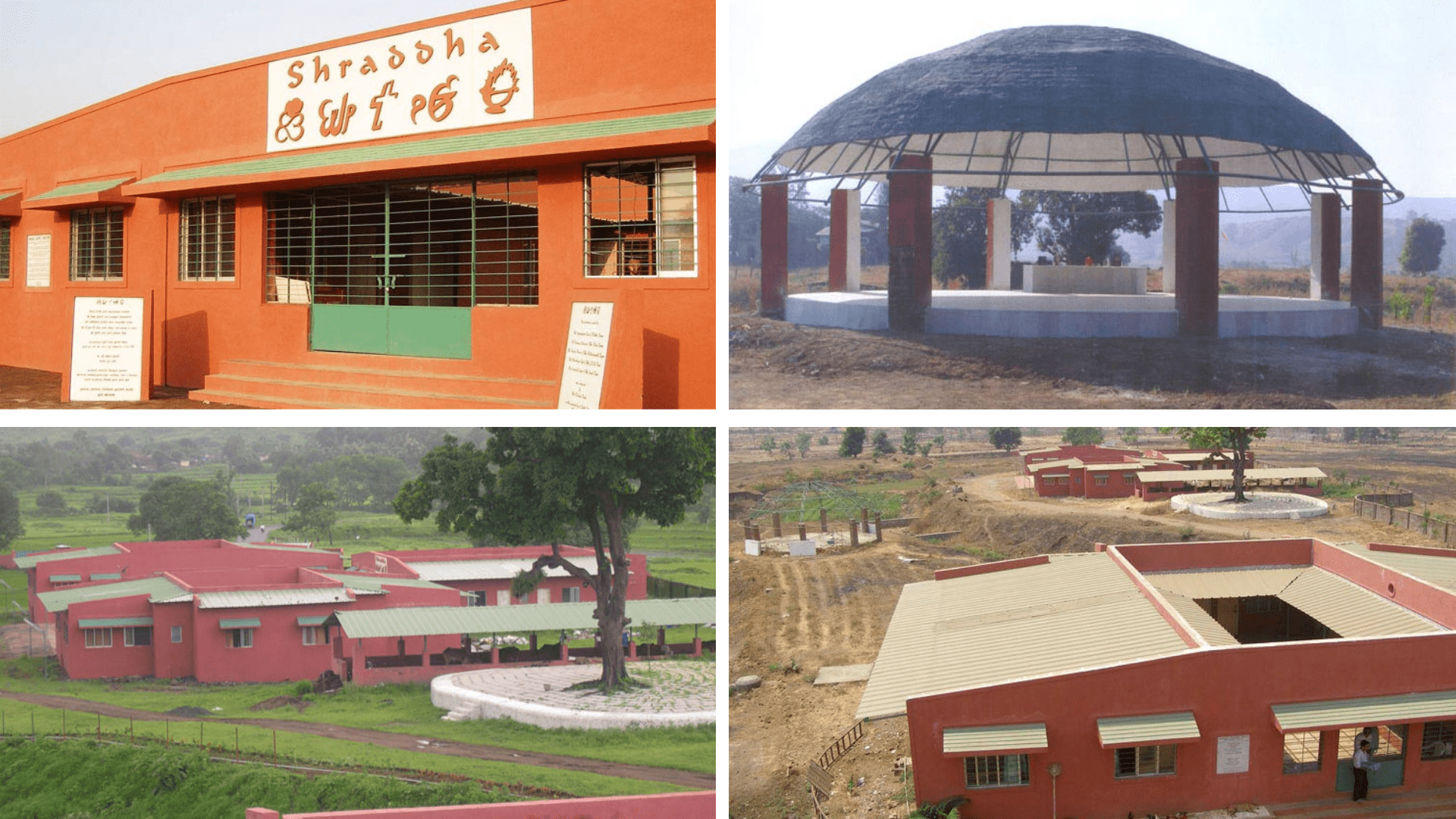

Views of the Shraddha campus, including the dormitories and prayer/meditation center | Images from Shraddha Rehabilitation Foundation.

Rice cultivation by the patients | Images from Shraddha Rehabilitation Foundation.

Mittal Institute: You are the recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay Award for your dedication to the mentally ill. Can you share what this award meant to you?

Dr. Vatwani: My heartfelt opinion was that I did not deserve the Ramon Magsaysay Award. Statistics estimate that almost 1 million Indians are homeless and mentally ill. All that we had done was treat, rehabilitate and reunite a mere 7,000 of them through the date of the award. A fairly paltry, insignificant number given the magnitude of the problem.

Despite this, I accepted the award because it carried with it its own reputation, and I felt it would bring focus to the plight of the wandering mentally ill not just in India, but in the whole of Asia and the world. When my wife and I went to the Philippines, we saw mentally ill people wandering the roads. The psychiatrists with whom we interacted acknowledged and accepted their presence. It is ultimately a worldwide phenomenon, perhaps more in developing nations with their asymmetrical distribution of wealth.

I definitely feel that the award has helped bring a much-needed and long-overdue focus to the cause of the wandering mentally ill, bringing it out of the closet and into the open. The number of emails we are receiving from pan-India has shot up exponentially.

The big question, then, is not how many wandered mentally-ill are sheltered in how many shelter homes or NGOs across the world; instead, the question is how many wandered mentally-ill find their way back home, as implied in the Shraddha model. How many families are saved from the psychological morbidity associated with the separation from a loved one, and the physical loss of a possibly alive/possibly dead relative lost to mental illness? How many wandered mentally-ill are granted their constitutional right to not just stay sheltered, but to stay with their loved ones? It is these questions that have to be addressed.

Mittal Institute: What do you hope the audience takes away from your panel with Dr. Vikram Patel on the state of mental health in India?

Dr. Vatwani: On a practical note, each one of us can do a lot for the mentally ill around us. We cannot just wait and do nothing.

What is needed are not just laws (which on paper perhaps exist even now); what is needed is a huge awakening of society, be it at the government’s financial inputs level, their physical infrastructural levels, or at their human resources level (in terms of more psychiatrists, psychiatric social workers, nurses, and trained community volunteers).

At other levels, the private sector can do their respective worthy contributions; the corporate sector their mega-contributions; the NGOs can do their often selective (but effective) coordination and outreach to the interiors of India; the pharmaceutical sector can do their bit by giving medicines at cost or a little above; the funding agencies can chip in; the local governing authorities can do their bit by easing rules to meet priorities; the psychiatrists can do a lot (either through admitting the roadside destitute into their nursing homes or by giving free, regular visits to NGOs sheltering the destitute), and so on.

This talk is an attempt to bring focus on the role of emotions in global health and social medicine, and an attempt to exemplify the same through the work of Shraddha Rehabilitation Foundation with the wandering mentally ill roadside destitute on the streets of India. And perhaps to hopefully underscore that “In dark times, attempts are precious, they always matter.”

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subjects and do not necessarily reflect the views of LMSAI, its staff, or its steering committee.