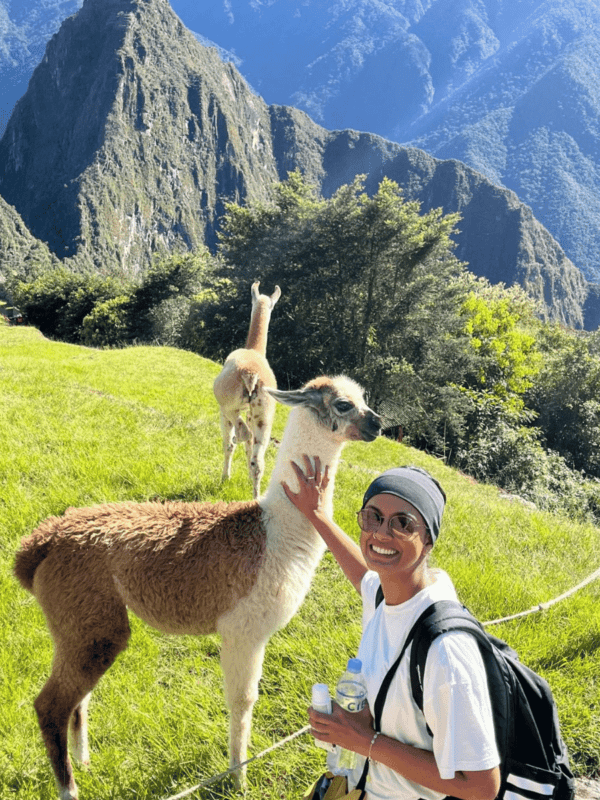

Anu K. Antony is the Mittal Institute’s Raghunathan Family Fellow 2023-2024. As part of her fellowship at Harvard, she is writing a monograph on the subjectivity and labor of Catholic nuns from the Syrian Catholic congregations of Kerala, India. In May this year, she set off to Peru to understand why more and more Catholic nuns from Kerala travel to South America for mission work. Apart from the ethnographic fieldwork, there was also some downtime for sightseeing and friendly encounters with Peru’s four-legged national symbols. Read her travelogue below!

Anu near Machu Pichu in Peru

Written by Anu K. Antony

This May, I traveled to Peru to explore the transnational migration of Syrian Catholic nuns from Kerala, India, to South America for mission work. This migration is a very recent phenomenon that began within the last ten years, and I am exploring it as part of my ongoing research on the subjectivity and labor of Catholic nuns from the Syrian Catholic congregations of Kerala. The findings of my research will be discussed in my upcoming monograph, which I am working on during my current tenure as the 2023-2024 Raghunathan Fellow at the Mittal Institute.

As an ethnographer, it was fascinating to experience the unraveling of a new field, but also overwhelming to deal with the new set of questions and frameworks presented by it. As an anthropologist of Christianity, it was humbling to be welcomed into the Malayali convents of Peru, where the images of the Virgin of Guadalupe adorn their chapels along with the figurines of Our Lady of Vailankanni and Malayali saints such as St. Kuriakose Elias Chavara or St. Euphrasia. The meanings generated through the co-existence of images and symbols are one of the first things that captured my attention during the fieldwork in Peru. These co-existences open the doors to the hitherto much less explored connections and exchanges between South America and South Asia.

I spent the first couple of days in Lima with two Malayali nuns who belonged to the Mathurai province of a foreign congregation serving in Peru for more than three decades now. From there, I traveled to Sayan in the Huaura province to stay a few days in a new Malayali convent established under the Huacho diocese in June 2023. Four Malayali nuns from the Congregation of the Mother of Carmel (CMC) – an ‘indigenous’ Syrian Catholic congregation with its headquarters in the Ernakulam district of Kerala, India – took over a vacant convent building that previously belonged to an Italian congregation. The Italian congregation dissolved the convent in 2021 due to a vocation crisis and a shortage of members to run the convent. After the Italian sisters left the parish, the convent building remained vacant until June 2023, when the Huacho diocese handed over the building to CMC and welcomed the Malayali nuns to their diocese.

Left: Visiting the Churrin convent with the nuns from Sayan convent. Right: A beautiful evening with nuns in the Churrin convent. Photos by Anu K. Antony.

The story is very similar for several other Malayali convents in Peru. Some of the convent buildings left by Italian and Peruvian congregations are now handed over to Malayali congregations, where the vocation crisis is yet to be a concern. Due to the number of vocations that Kerala’s congregations enjoy, bishops from dioceses across the globe often invite and encourage the indigenous Malayali congregations to send their members to different dioceses outside India. For example, I learned from the nuns in Sayan that one of the Bishops from a Peruvian diocese visited Kerala a few years back, and, impressed with the number of vocations in Kerala, he wrote to the Mother General of CMC and invited them to expand their global missions to Peru.

Beyond Peru, the Malayali congregations are also expanding to other countries in South America, such as Ecuador and Brazil. The vocation crisis faced by the congregations in Europe and the Americas has led to a shortage of religious labor in many parishes and dioceses, which opened new avenues for the global mission of Malayali congregations. However, this is not the only reason for their expansion. Their global mission, according to the nuns, is part of their congregation’s vision and charism as well as a central aspect of an individual nun’s subjectivity as a sojourner in ‘this’ world. Moreover, the cultural similarities of Catholicism make these expansions to South America relatively easy, according to my respondents. In fact, they describe the move as much easier than adapting to the cultural differences and hostility towards their missions in some of India’s Northern states.

The vocation crisis faced by the congregations in Europe and the Americas has led to a shortage of religious labor in many parishes and dioceses, which opened new avenues for the global mission of Malayali congregations.

The ethnographic data leads me through the nuances of Catholic networks and the connections made possible through the religious labor ‘on move’ within the regions of the Global South. In other words, I look at the expansion of Malayali congregations to South America and other locations in different parts of the world as a continuation of the questions of subjectivity and labor that I explore in my larger research. I argue that this recent proliferation of Malayali female congregations in Peru (or South America in general) should primarily be seen as an expansion of their global missions to newer and friendlier soils, but nuanced and multiple aspects motivate these expansions. I will be discussing those aspects elaborately in the monograph.

There are not many other studies that investigate the cultural and religious exchanges between Asia and South America. A few studies investigate the connections, international affairs, and trade relations between these regions, but they mostly focus on connections between Latin America and China, Korea, and Japan. Meanwhile, studies that investigate the cultural/religious exchanges or networks between South Asia and South America are almost non-existent. Looking into the networks of Catholicism, especially Eastern Catholicism, is crucial to explore these exchanges.

Left: Preparations for Holy Mass. Right: Feast procession in a village church in the Huaura province. Photos by Anu K. Antony.

After my stay in Sayan, I visited convents in Chancay, Churrin, Cusco, and Arequipa. I stayed with the nuns and traveled with them to different villages for pastoral and mission work. Interestingly, unlike the Malayali convents in the Global North, where they own and work in the institutions owned by the diocese, the nuns serving in Peru mostly engage in pastoral work.

Throughout the trip, I had elaborate insightful conversations and conducted some formal interviews as well. I went with a focused plan prioritizing the themes I will address in my monograph and hence, I had very structured and precise questions in mind. After finishing my monograph, I would love to go back and visit more Malayali mission regions in Peru and other parts of South America for a more detailed and larger study.

In the book, I will look at two more locations, Italy and Iraq, to better understand the transnational religious labor migration from Kerala’s female religious congregations. While the Malayali missions in South America tell us the story of its most recent expansions, these other two locations help us understand the routes of gendered religious labor migration facilitated through the affective historical links of the Syro-Malabar church. The Syro-Malabar church with its peculiar affective history is hierarchically part of the Roman Catholic papal hierarchy and at the same time liturgically affiliated to the Chaldean Catholic church, which has its headquarters in Iraq.

In my monograph, I will also look at Italy and Iraq. While the Malayali missions in South America tell us the story of its most recent expansions, these other two locations help us understand the routes of gendered religious labor migration facilitated through the affective historical links of the Syro-Malabar church.

I would like to highlight that my fellowship at the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute helped significantly in facilitating my fieldwork in Peru. It allowed me to utilize connections and networks of Harvard alumni and affiliates who connected me with the religious networks in Peru. I am particularly grateful to Ms. Britt Ludvigsen, a Peruvian Harvard alumni and affiliate, and Jimena Codina, the program coordinator of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard University, for introducing me to several scholars and officials working on South America. The amazing resources at Harvard and the connections that open up through the networks of Harvard affiliates made this fieldwork viable.

And yes, no one can come back from Peru without exploring the Peruvian highlands and the wonderlands of the mighty Incas! I enjoyed the splendor of the cultural remains at Machu Pichu, read and learned a lot about the Inca civilization, and petted cute baby llamas in the Andean ranges.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subjects and do not necessarily reflect the views of LMSAI, its staff, or its steering committee.