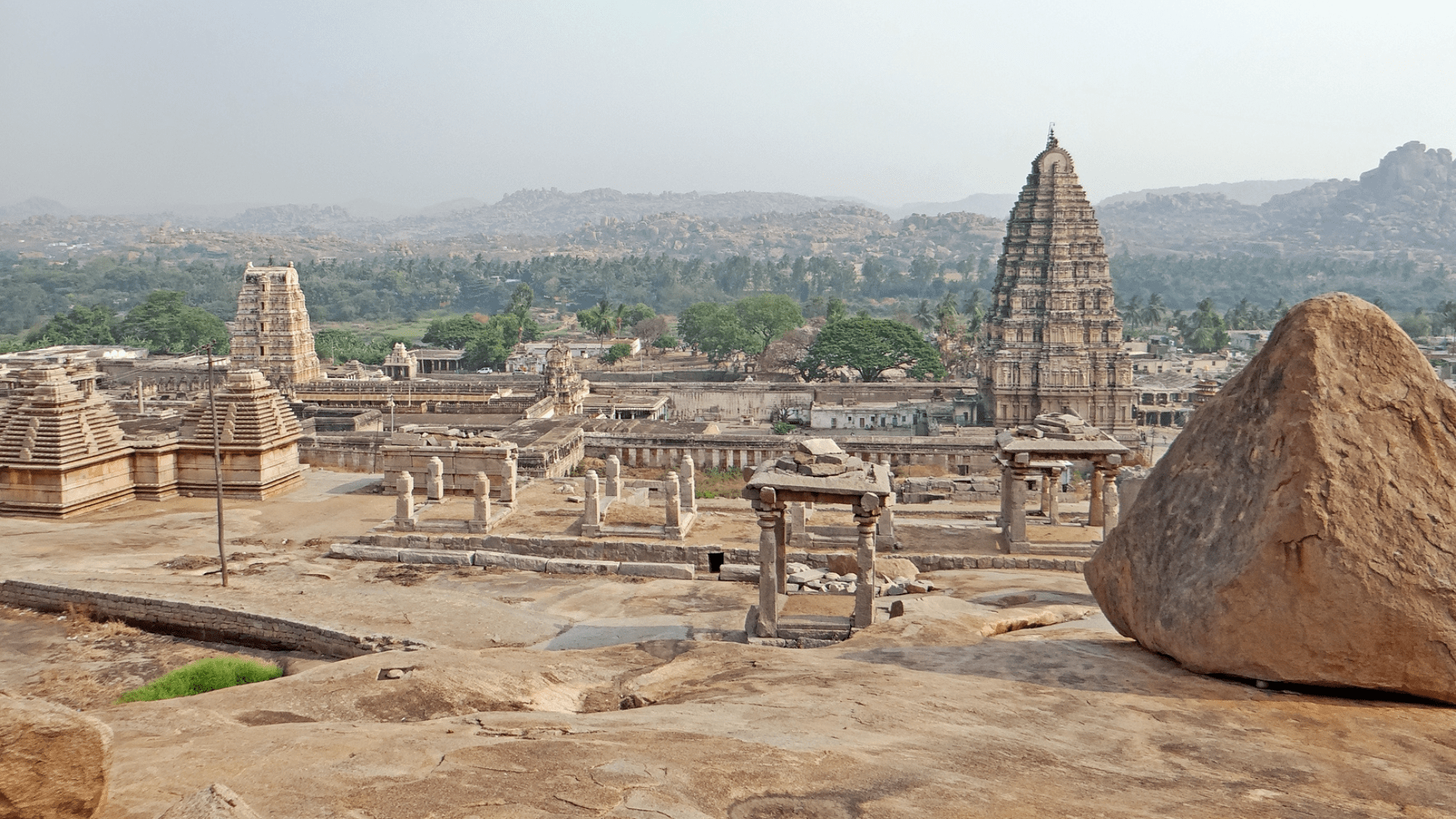

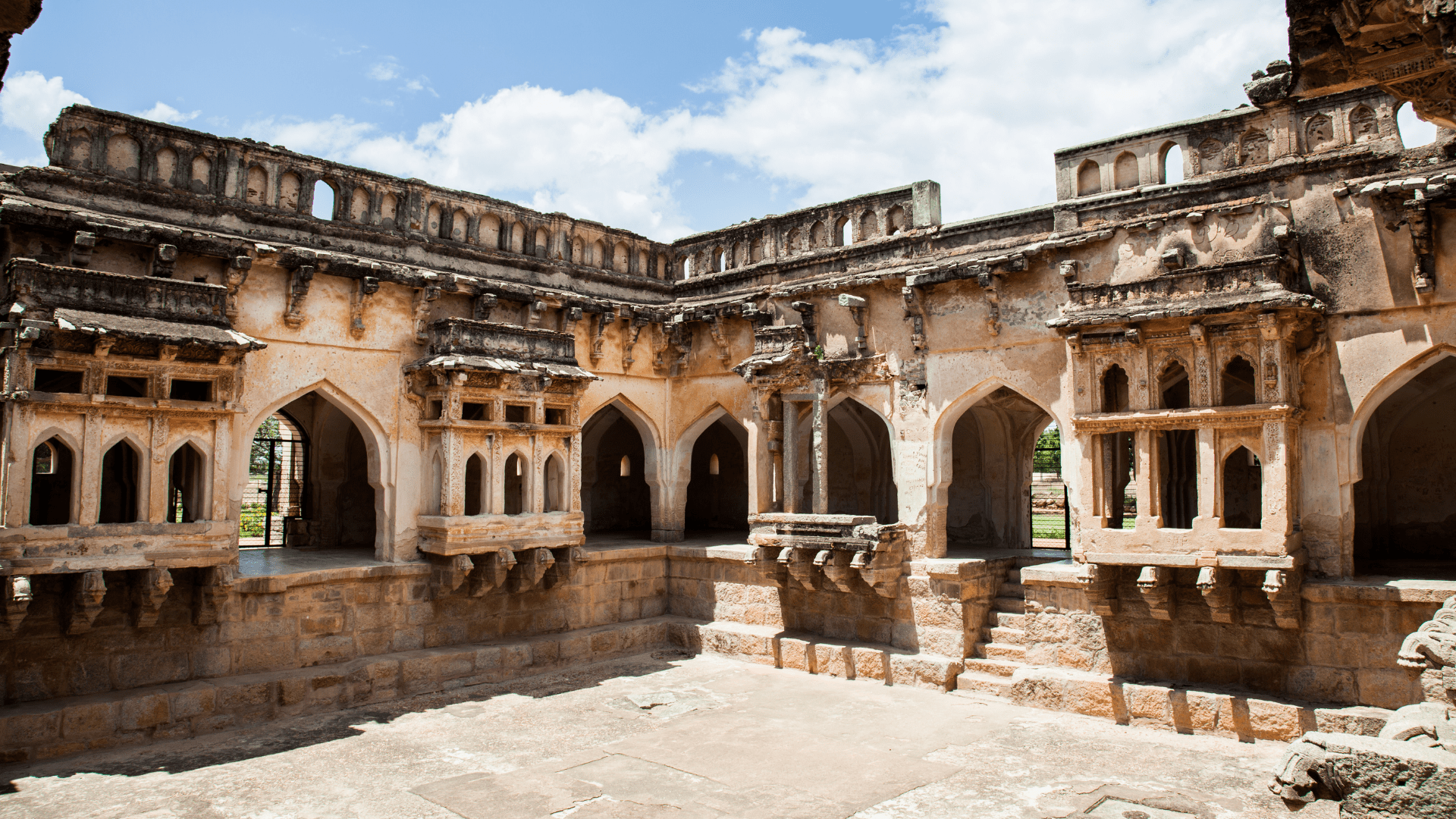

The ruins of Hampi Vijayanagara.

Dr. George Michell, a world authority on South Asian architecture, has made the study of Deccani architecture and archaeology his life’s work. He will join us for a discussion on “Unveiling Hampi Vijayanagara: An Illustrated Lecture on India’s Ancient Capital” on October 7. He will be introduced by Jinah Kim, George P. Bickford Professor of Indian and South Asian Art and Professor of South Asian Studies at Harvard University, with the Q&A moderated by Rahul Mehrotra, John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization at Harvard Graduate School of Design.

We spoke with Dr. Michell about how he got started in the field, his work at the medieval Hindu ruins of Hampi Vijayanagara, and what attendees can expect during his talk. An edited transcript of our discussion is below.

Mittal Institute: You were born and raised in Australia, and trained as an architect before transitioning to the field of archaeology. Can you talk to me about how your interest in South Asian architecture first evolved?

George Michell: In the architecture course that I did in Melbourne, we had a year of what was called “Asian architecture,” and this was given by a teacher who was very involved with Indonesia, which, of course, is nearest to Australia. He showed us pictures of all sorts of wonderful things from all across Asia and from the Middle East through to the Far East.

George Michell

At the end of that year, there was a student exchange trip with India because our summer vacation coincides with winter holidays in India. I joined one of these trips and eventually gave up on this exchange and went off on my own and wandered around India looking at ancient architectural places because I was an architecture student. I got back to Melbourne completely fascinated with this experience. When I finished my course in architecture and did not enjoy working as an architect, I decided I would like to pursue this. I went to the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London and registered for a Ph.D., and I had to choose a topic. I chose these early Deccan temples of the sixth, seventh, and eighth centuries at a place called Badami, and I did my studies on this early Deccan Hindu architecture though photography and by making measured drawings.

Mittal Institute: For the past 30 years you and American archaeologist Dr. John M. Fritz have researched and catalogued the enormous ruins of the city Hampi-Vijayanagara, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Can you share a brief history of Hampi Vijayanagara with our readers?

George Michell: Hampi was set up as an artificial capital. It hadn’t been a city prior to the 14th century, and it became the most important and wealthiest place ruling all of South India. Its influence lasted a couple of hundred years, until eventually they lost a disastrous battle in the middle of the 16th century against the Sultans to the north, and the place was sacked; the army defeated; and the Vijayanagara kings abandoned it. It had a limited life and therefore is quite interesting to study because it hadn’t been built upon later and later and later, like a lot of ancient places. It was just preserved, more or less, up to the middle of the 16th century. The remains are scattered over an enormous area, 25 to 30 square kilometers in this landscape – it’s a sort of wilderness of granite with a great river running through it. It’s a very beautiful, remote, and mysterious place filled with the remains of this great city.

The remains are scattered over an enormous area – it’s a sort of wilderness of granite with a great river running through it. It’s a very beautiful, remote, and mysterious place filled with the remains of this great city.

Virupaksha temple at Hampi.

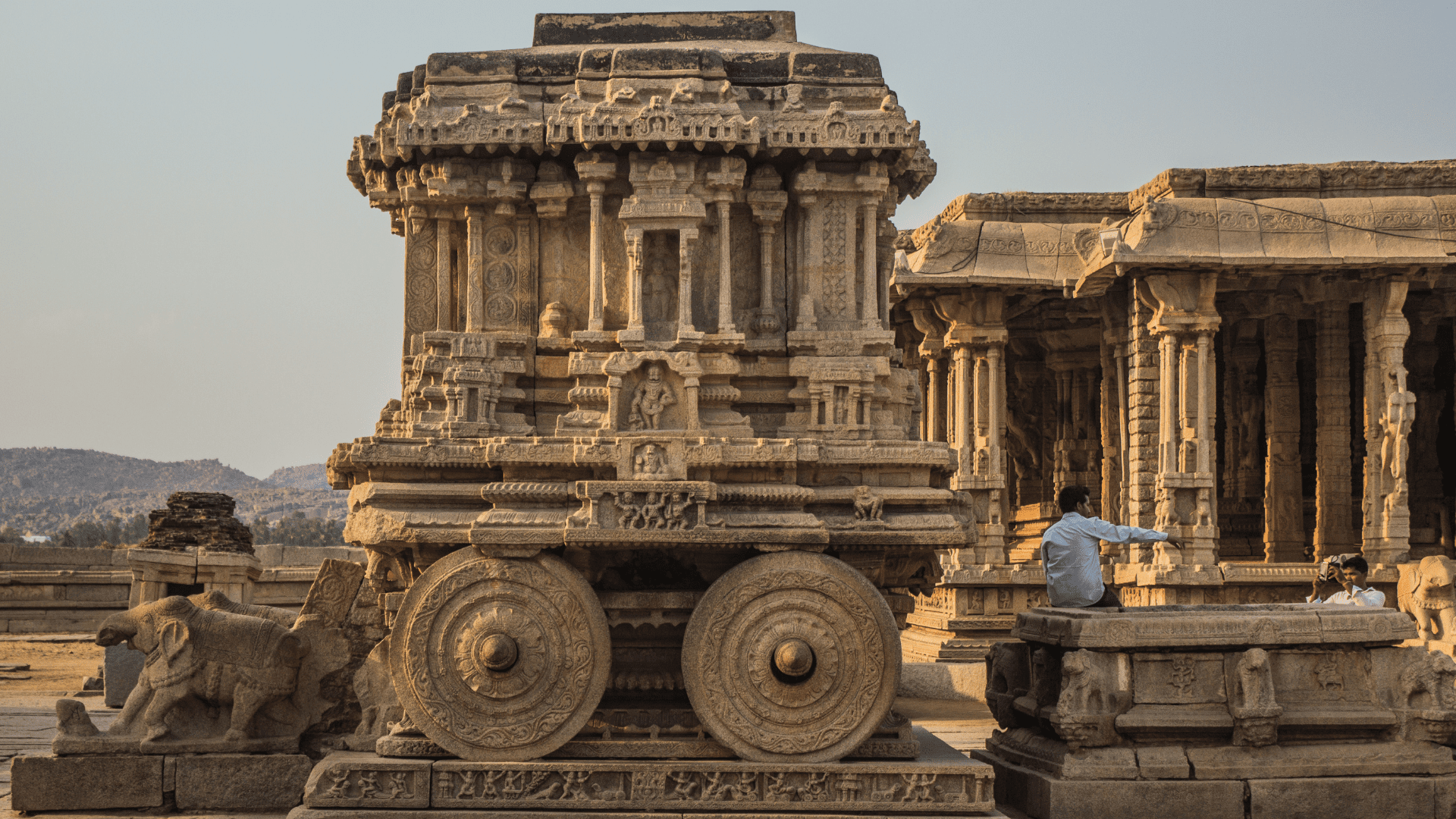

The Garuda shrine in the form of stone chariot at Vitthala temple.

Mittal Institute: How did you and Dr. Fritz begin working there?

George Michell: In the mid ’60s, Hampi was off the track of visitors. In the ’70s, when I was working at this place called Badami a few times, eventually somebody said to me that I really should make an effort and go look at it. I made a few trips, just briefly. It was all very confusing – this enormous landscape with stuff all scattered all around. I didn’t really get the hang of it. But towards the end of the ’70s, I thought, maybe I should make an effort. Unlike most of the historical sites of that period, this is not just another set of temples. It’s a complete city – a royal city. It has things in it that you don’t find anywhere else, like palaces and stables and pleasure pavilions and military architecture. It presented a whole set of different architectural types and things to study. So that’s how I got sort of fired up about it and began to do research there. .

Dr. John Fritz, an American archaeologist whom I met, started to go with me every winter where we had a tented camp – it was very like a 19th century expedition – which was provided by the local archaeologist. These days, nobody goes there and comes back and says, it wasn’t worth the visit. It’s now one of the great tourist sites of India, as you may know. But it wasn’t in the ’80s. There was no bottled water, there were no hotels, there was nowhere to stay. It was remote. But we had teams of young students of architecture and archaeology. They came from India, America, Australia, and the UK. It was like a field school. People would come and last for at least three weeks, if not a couple of months. And we set about mapping, measuring, and photographing and studying the place.

Mittal Institute: Can you tell us more about what research life looked like for you and the student volunteers at the camp?

George Michell: John managed to find a little bit of funding through the Smithsonian institution, which paid for the camp. So once the students came, we could pay for their cost of living. But nobody got paid; it was totally voluntary, and it wasn’t associated with any institution. It was a completely independent setup. We had to have a permit to do it, which we got from the central government. We were not allowed to excavate or to do any restoration. It was a hands-off operation.

Since there was so much to see and observe, it kept us busy because there was so much to measure, map, and record. And because the site was so seductively beautiful and it was such an adventure to wander around this great site, in the middle of nowhere…the students just loved it. We never had any trouble recruiting young people, many of them from Indian schools of architecture and archaeology, and many of them from other places around the world.

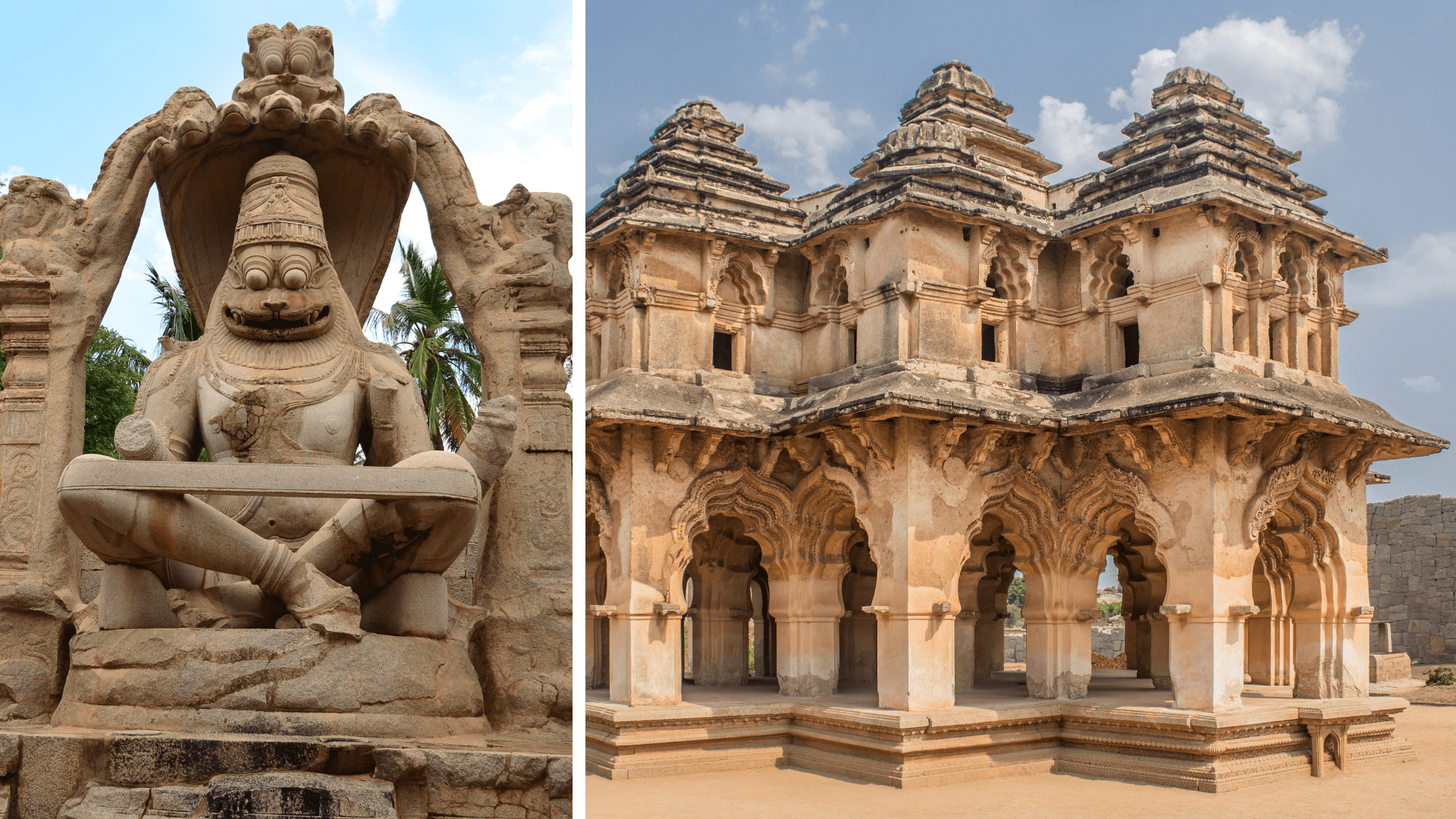

Left: Yoga-Narasimha monoliths carved in-situ; right: Lotus Mahal.

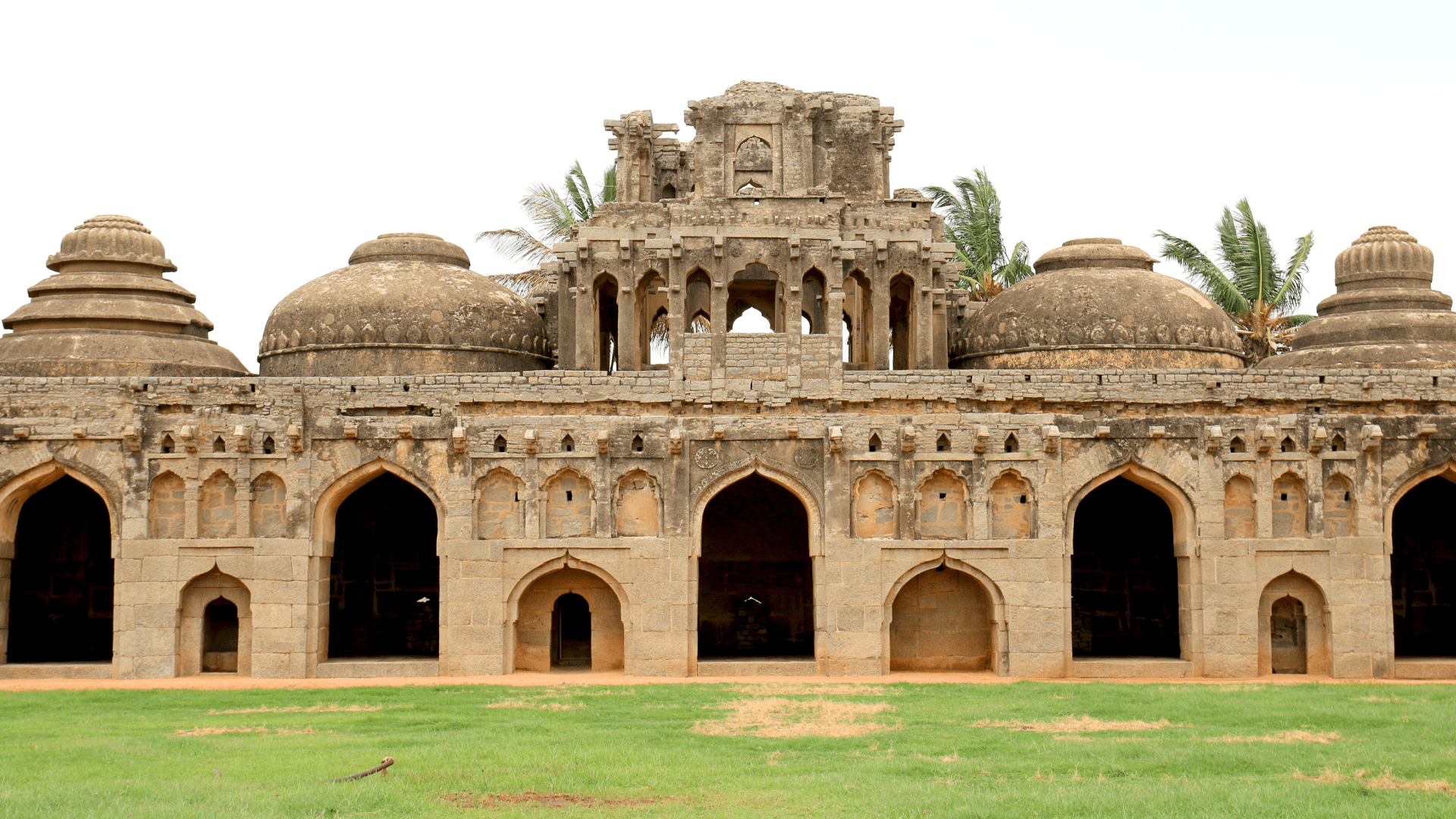

Elephant stables.

We had a drawing office, and in the afternoons, we set up drawing boards for the students to put everything down in pencil. Everything had to be finished in pencil because we had no university to go back to finish – everything had to be done on the spot. John and I would then give critiques of the work and send them back the next day to remeasure and redo it. It was quite like a training camp. This went on for 20 years.

Mittal Institute: How did your work change after it became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1986?

George Michell: The site started to have more prestige, and we helped a bit because we made some maps as the Indian government didn’t have reliable maps of the site. This was all done informally, and happily, between the people we knew, whether they were central government or state government. There were local Indian archaeologists there at the same time were also uncovering things, digging down and finding buried palaces and remains. All of this went on at the same time – we were doing our work on the surface, and they were doing it under the surface.

By 2021, the money ran out. There was no more Smithsonian support. By then we had done enough. John and I decided we would stay in India in the winter, but we’d go to Goa, on the Arabian Sea. We started to put our materials together, and we wrote everything up; we then illustrated and published our materials. We gave talks at various places in the U.S. and we participated in conferences and lectures.

Queen’s Bath built in Indo-Islamic style.

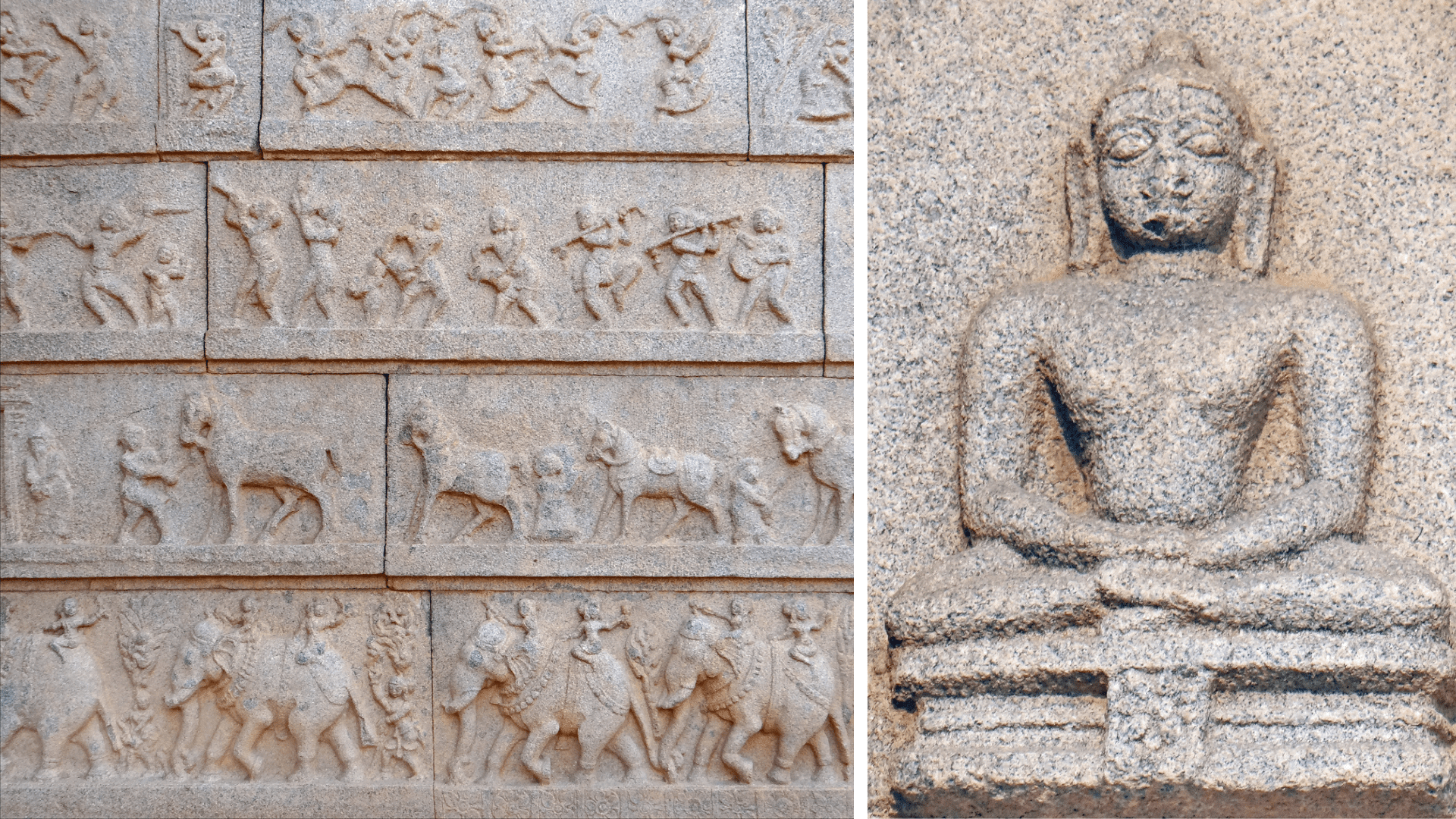

Left: Hazara Rama temple walls show Hindu processions; Right: The Buddha inside the temple.

Mittal Institute: You have published over 50 books, including Late Temple Architecture of India, 15th to 19th Centuries, and, together with Dr. Helen Philon, Islamic Architecture of Deccan India. What has been your favorite publication and why?

George Michell: We worked with an Australian photographer named John Gollings who specialized in architecture. John and I had been in architecture school together, but he didn’t want to build; he wanted to photograph. And he always said to me, one day I’d love to come to India, but it’s got to be something worth photographing. So John Gollings came in ’81, at the same time as John Fritz came. John Gollings went beserk because it was this beautiful, picturesque, marvelous place; in fact, he came back for many, many years and photographed the remains.

One of the things that happened while we were working in the ’80s was a discovery of 19th century photographs of Hampi. These photographs were from 1856 – a very early date for photography anywhere in the world, even in Egypt or Greece. But from this site in Hampi, 65 waxed paper negatives were discovered, which we’d had no idea about. Gollings decided he would do a rephotography project. He would go back and take the exactly the same view today as it was in 1856 so that’s another dimension to our project.

Eventually we did a wonderful book called City of Victory, which is what Vijayanagara means. And with John Gollings’s photographs and a text by John Fritz and myself, we published it 30 years ago by Aperture in New York, a photographic book house. We’re now in the process of redesigning it and reissuing it after all these years.

Mittal Institute: Can you give us a sneak preview of your upcoming lecture – what can our audience expect?

George Michelle: The talk is about the meeting of two people with two different backgrounds—myself, of course, with a history of doing architectural documentation on historical places in India, and John Fritz, who had been trained as an archaeologist at the University of Chicago in what was called the new archaeology—who brought these two different approaches towards interpreting the site. The talk will be about what the Hampi site is, and how John and I read the site as a city, not just as a group of monuments. Nobody who goes there today is unaffected by Hampi – the impact of the site is enormous. John and I fostered this sort of environment for collaborative research for many decades.

Mittal Institute: What is next for your Hampi research?

George Michell: John died at the beginning of last year. He was 83. I will be 80 by the end of the year. This is not the time to start new things, but I’m now involved in tying up things that need to be finished. In fact, all of our materials from this whole project – 25 years of fieldwork – have gone to the British Library in London, which means they will be available for any interested people in the future.

One of the great projects that John worked on but didn’t finish before he died was an archaeological atlas. This Vijayanagara archaeological atlas is an enormous project. There are about 300 maps with 35,000 observations, and it shows what you can see of a past habitation. Every single scratch on a rock, every single bit of tumbled structure, everything that is human, that’s not natural, is recorded on these maps. I’ll show one or two maps during my talk. We have a foundation who’s paying for it to be finished, and it will be issued digitally. And I’m hoping I can find some money to issue the maps on paper because I’m not sure that everything should be digital. My job, my responsibility, is to see all our work tied up in the best possible way.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subject and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mittal Institute, its staff, or its steering committee. All Hampi images from Wikimedia Commons.