The Mittal Institute awarded 14 student grants this winter, allowing students to set out for locations across South Asia to complete research, internships, or language studies. Allen Wang, a Master in Design Studies (Ecologies) student from the Harvard Graduate School of Design, traveled to Nepal’s Kathmandu Valley and Pokhara to complete a research project on envisioning climate-resilient futures for the ecotourism Industry in Nepal. Allen details his experience in the grant report below.

Interested in a summer 2025 student grant? Apply by Friday, February 21.

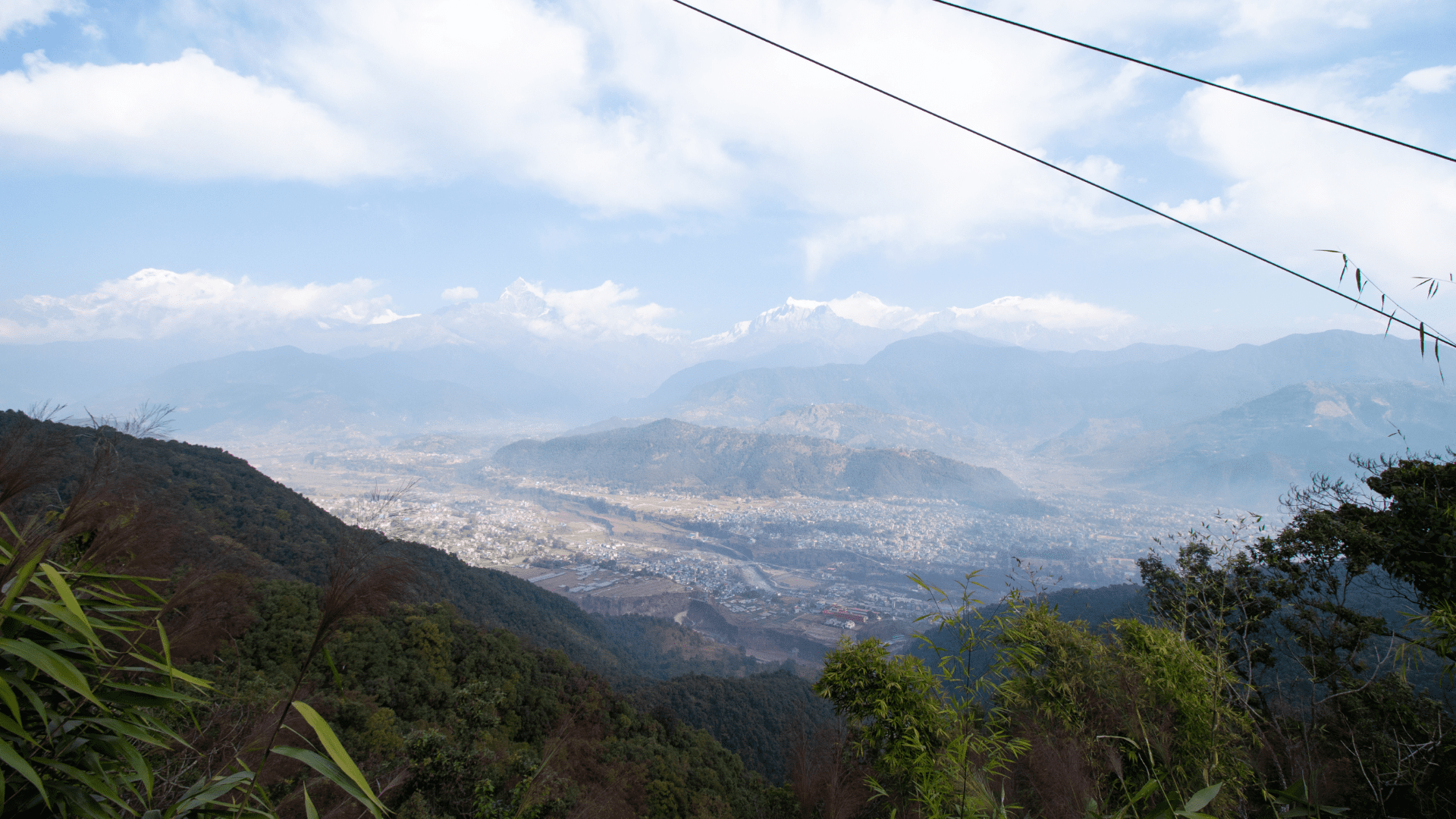

Allen Wang, MDes ’25, at Sarangkot, with the Annapurna range in the background.

Mittal Institute: Allen, what were your goals with your student grant, and why did you pursue this project/location?

Allen Wang: I’ve been looking at Nepal’s ecotourism industry as a case study since January 2024. As someone with a background in service design and currently in a design studies (ecologies) program, I chose this site as the confluence of those two fields: to explore service-delivery in the context of landscapes. In May 2024, I completed two weeks of fieldwork in Sagarmatha National Park (home to a prolific trekking industry centred around Mount Everest, also known as Sagarmatha or Chomolungma). In that trip, I focused on documenting how the pursuit of service-delivery (e.g., guides, logistics, hospitality, retail, waste management) impacts the environment and how the environment shapes services in turn.

After a semester unpacking my findings through coursework, I realized that I had more questions. I wanted a more projective approach, to describe not just the way things work today but to understand anthropologically what futures were at stake in relation to pollution/waste, climate change, and disaster risk. How have recent events shaped the way people in Nepal’s ecotourism industry think about the future? What do economic growth and infrastructure development mean to locals when balanced with questions of environmental and cultural sustainability? And I had a few solution hypotheses I wanted to get people’s feedback on.

“How have recent events shaped the way people in Nepal’s ecotourism industry think about the future? What do economic growth and infrastructure development mean to locals when balanced with questions of environmental and cultural sustainability?”

So, I went to Kathmandu for fifteen days and serendipitously found myself in Pokhara as well through a few snowballing referrals.

View of Kathmandu at sunset from Swoyambhu Temple, atop a hill in the west of the city.

A view of the Annapurna range from the trail to Sarangkot.

Mittal Institute: Tell us about the most impactful component of this experience.

Allen Wang: It was a productive fifteen days. In 93 hours of fieldwork, I engaged 70 stakeholders through 28 semi-structured interviews (mostly with government and NGO stakeholders), 30 walk-in interviews (mostly with local storekeepers), and site observations. I shared 38 teas or coffees with interlocutors (as many as six cups in a single day!), as well as 11 meals.

The most impactful part of this fieldwork was the opportunity to hear people tell stories about their past experiences and their outlook on the future. Some storekeepers described their experiences during the 2015 earthquake, when they were working in the very same stores we were chatting in. They described the initial shock of the earthquake followed by the persistent terror of the aftershocks that came every few hours or days for some time. They described pulling people out of collapsed buildings, and the month spent in the temporary shelters. We could still see cracks in some of the walls. And there was frustration with the central government, like how it had agreed to pay some percentage of the rebuilding cost for people’s homes, but only on a reimbursement basis, which meant that if you couldn’t afford to rebuild your home in the first place, you saw none of the relief money.

In May, I had heard it described how the trauma of the earthquake transfigured Nepali paradigms into more of a “YOLO” mentality, that of living for today because a natural disaster could snatch away the future at any moment. Through my conversations in December, it seems to me that the psychological impact has been more diverse. It was also not so common for many to dwell on the earthquake; a lot of people seem to have moved on. And when I asked some storeowners about their future plans for another natural disaster, or for climate change, most adopted a reactive ethos or emphasized their own powerlessness: “I have no plan for the future; God will decide.” If we see ourselves as moving through time in bubbles, these bubbles have shrunken for many.

“In May, I had heard it described how the trauma of the earthquake transfigured Nepali paradigms into more of a ‘YOLO’ mentality, that of living for today because a natural disaster could snatch away the future at any moment.”

More analysis remains to be done, but this experience was immensely helpful in bringing me closer to a country that I had no prior connection to as the topic of my study.

Mittal Institute: Bring us into your daily life on your grant program. What was it like? Who were you meeting? What institutions were you visiting?

Allen Wang: Each day was different, but on average, I spent 10–12 hours each day (including weekends) either conducting fieldwork, commuting to fieldwork, planning fieldwork, or writing down field notes. In addition to ~50 small businesses and storeowners, I interviewed stakeholders from 14 organizations, including the Nepal Tourism Board, local waste management or environmental education groups, the oldest and largest plastics recycling facility in Nepal, stakeholders in the trekking/mountaineering industry, and others.

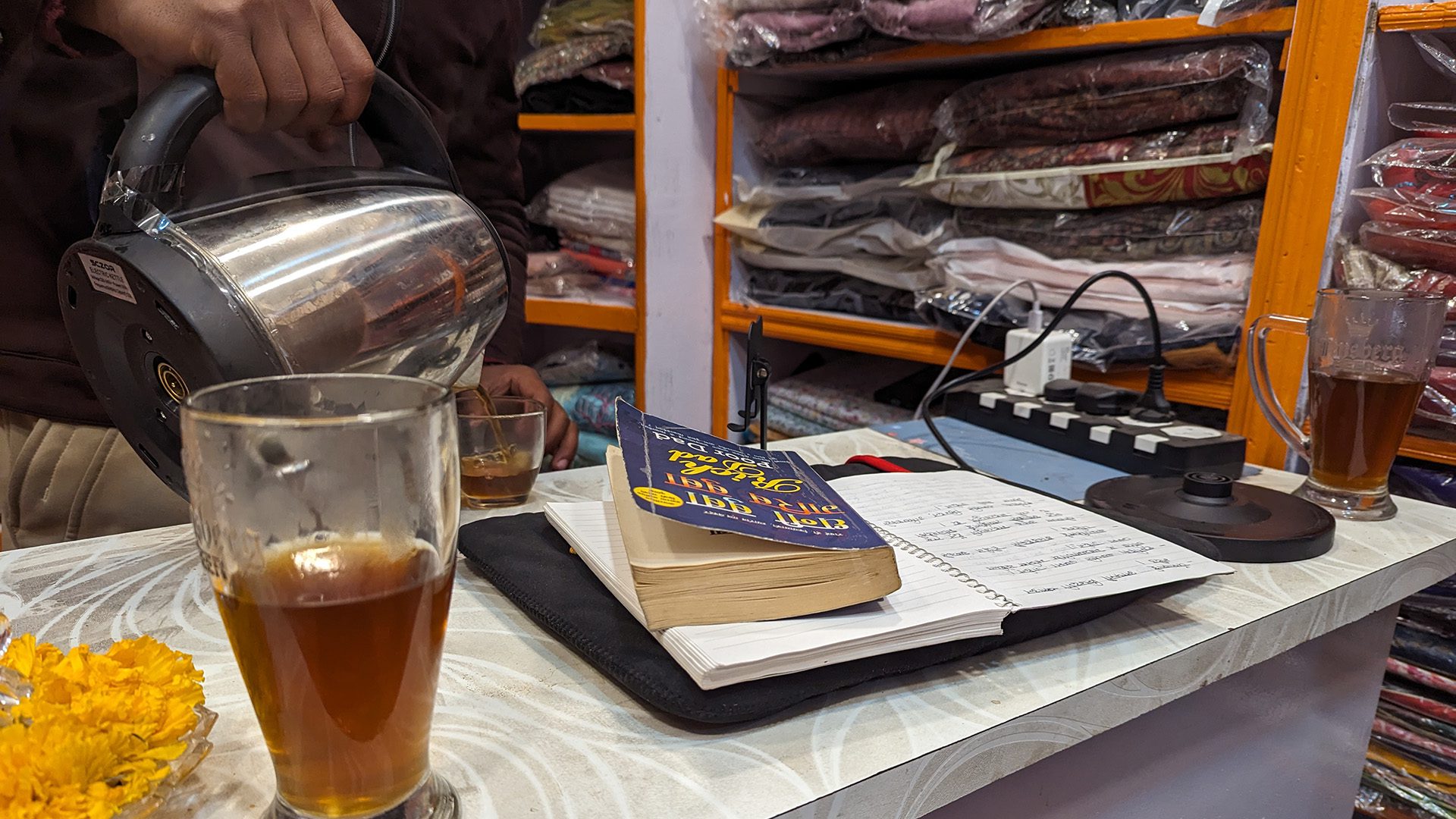

One of many storekeeper interviews over coffee/tea.

On my most prolific day, I managed to get six appointments lined up (totalling around 10 hours of engagement time): 9 am interview, noon interview, 2 pm interview, 4 pm interview, 6 pm interview, and a 7 pm dinner. The rideshare app Pathao was invaluable in helping me get from place to place across the city on motorcycles, though I also learned that Kathmandu traffic was unreliable and I needed to leave more time between meetings. Outside of meetings, I enjoyed trying new restaurants and wandering around psychogeographically.

“On my most prolific day, I managed to get six appointments lined up (totalling around 10 hours of engagement time): 9 am interview, noon interview, 2 pm interview, 4 pm interview, 6 pm interview, and a 7 pm dinner.”

Several people were instrumental in making my project feasible. In particular, the Governance Lab helped me engage a recent graduate to serve as an interpreter for the storeowner conversations, and he also helped me plan five days of my Kathmandu itinerary to reach tourism-relevant locations (Swoyambhu, Thamel, all three Darbar Squares, and Nagarkot). In Pokhara, a classmate’s husband’s father was a retired trekking guide and he connected me to many locals as well as took me on a day-hike along the trail to Sarangkot—a key fieldwork site because it highlighted the way poorly-considered road-building posed a threat to tourism livelihoods. Some folks I had met back in May were willing to generously host me or have me over to share a meal with them. Many others, too, helped with snowballing stakeholder recruitment in other ways.

Mittal Institute: How will this experience help you to reach your academic goals?

Allen Wang: My fieldwork in Nepal will comprise the foundation for my capstone project in my program’s final semester—which I’ve started working on. While the May trip focused on documenting service-delivery and ecology in a rural trekking region, this December trip focused on the urban, the behind-the-scenes, and human perspectives. In December, I also came with specific follow-up clarifying questions and solution hypotheses that I hoped to run by people. I accumulated somewhere in the vicinity of 8,000 photos and other visual media (across both trips), 41 hours of interview recordings (from December alone), and other forms of archiving. I gathered a variety of trekking maps (including the most up-to-date editions as well as historical editions older than me, to track changes over time) and souvenirs (my favorite being recycled plastic pellets from PET bottles collected across Nepal). In my capstone project, I will push towards an ecological and conceptual analysis of the topic to justify an appropriate form of intervention.

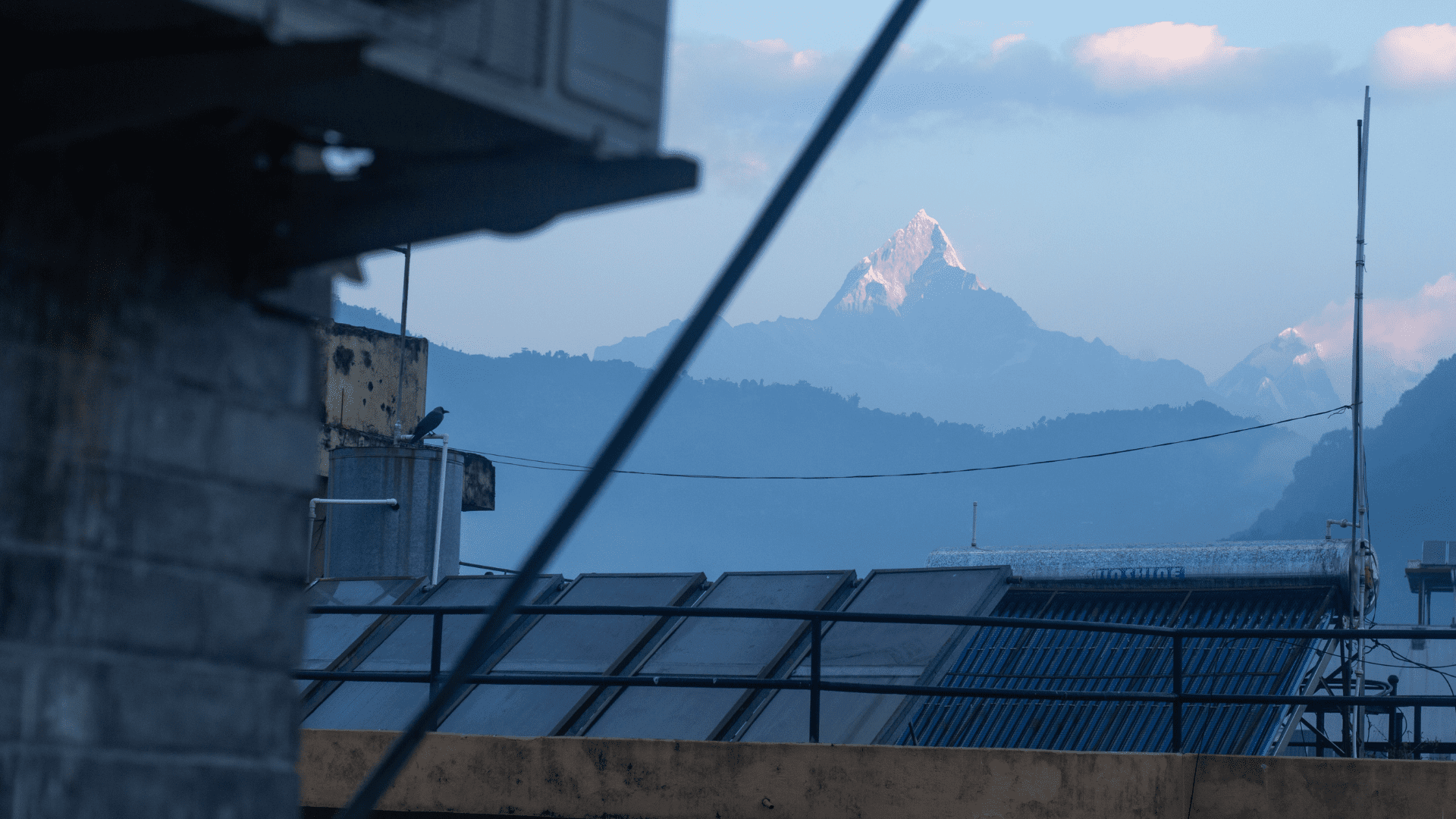

Machhapuchhare (nicknamed “Mount Fishtail”) viewed from Pokhara at sunrise. Locals frequently cited its lack of snow in recent years during winter as a signifier of climate change.

A part of the now-little-used trekking trail from Pokhara to Sarangkot. The road that obviated it can be seen from behind the trees.

Towards this end, the December fieldwork also broadened my perspective around the challenges that were top-of-mind for people. Whereas I had been thinking in terms of the sustainability of ecotourism (i.e., how to minimize the environmental damage of waste), I found many interlocutors speaking more about the trend of youth leaving rural areas and the country as a whole in search of better education, jobs, and quality of life. Many of the younger interlocutors even asked me for advice on getting into US graduate schools. So, while the ecological challenges are very salient, perhaps there is a simultaneous challenge around cultural sustainability. How do we envision a country’s future if so many of its people have lost their optimism for said future?

“While the ecological challenges are very salient, perhaps there is a simultaneous challenge around cultural sustainability. How do we envision a country’s future if so many of its people have lost their optimism for said future?”

Meeting stakeholders in person was important for helping me cultivate relationships which I will leverage subsequently in the project, particularly for follow-up validation questions and for disseminating my results. I don’t think it’s coincidental that most of my favorite and most productive conversations were with people I had met back in May and was now coming back to see again. Some stakeholders also told me how they were wary of researchers coming in and extracting knowledge from the community without giving back. It will be crucial for me to avoid falling into this same trap.

More broadly, I am interested in fieldwork and international travel as a way of developing and diversifying my research portfolio. I appreciate the opportunity to develop my primary research skills in an academic-infused design context, focusing on ecology and anthropology rather than the business-minded and value-driven work I had done previously in my professional career. I will undoubtedly feature this work in future applications—whether for academia, consulting roles, or otherwise.

Mittal Institute: What was the most memorable moment for you?

Allen Wang: There are too many memorable moments to share. And the time went by so quickly in hindsight. As someone fascinated by the phenomenological experience of travel though, I think what takes the cake is near the very beginning of the trip—that first night in Thamel when I left the hotel to wander in search of a restaurant for dinner. And realizing that things were largely how I had last seen them when I left in May. I think I take it for granted that things will be the same when I return. And there’s a magic to it, when they actually do remain familiar. Trying some of the same foods and walking some of the same streets again was a wonderfully nostalgic experience. I feel more comfortable in Thamel than in many other places, perhaps because my identity as a tourist shields me in a sort of anonymity that I don’t have back home. Or that feeling of seeing an old friend from May for the first time in months.

It remains to be seen how reliable the future will be in the face of climate change, geopolitical tensions, and the constantly evolving nature of tourism itself.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subject and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mittal Institute, its staff, or its Steering Committee.