The Program for Scientifically-Inspired Leadership (PSIL) brings together Harvard undergraduates, local college students from India, and underprivileged high school students in India for a week-long residential learning experience. Launched in 2019 by Dominic Mao, Assistant Director of Undergraduate Studies in Harvard’s Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, PSIL is partially funded and administered by the Mittal Institute. This past January, Mao and Andrea Wright, Assistant Dean of Harvard College, led a team of Harvard students to India. After previous camps in Manipur and Telangana, PSIL expanded to Goa for the first time in 2025. Mao wrote an update about the experience, found here.

Merlin D’souza ’25, Human Developmental and Regenerative Biology and Global Health and Health Policy, was part of the five-person Harvard undergraduate cohort, and she shares her own dispatch, below.

“We fought over these.”

My instructor fellow, a Goan teacher in training, stated this after the foldscope lesson we delivered. Foldscopes are paper microscopes. My instructor fellow shared that they had used it in their biology class sharing one amongst their group. Through PSIL,102 students were provided foldscopes, enabling them to explore science affordably outside the classroom.

Assembling these devices, though, tested my students’ patience and persistence, yet their joy upon successfully using them was unforgettable. They kept passing them to one another as they looked at the fabrics of their shirts. After the activity, the students carefully stored their foldscopes away, but I urged them not to simply preserve them as keepsakes. Instead, I encouraged them to use these tools actively—to examine familiar insects from new angles or study plants up close.

Merlin D’souza ’25, one of the members of this year’s Harvard undergraduate teaching cohort.

“Teacher, teacher you’re cheating!”

The memory still makes me smile—my student’s exasperated protest when I deliberately reshuffled the capstone groups after noticing he’d been paired with someone he already knew. At the start of our program, our teaching team of five Harvard students and five Goan teachers-in-training wanted to tackle the rigid social separation between boys and girls. Initially, we had to physically orchestrate the seating arrangements, moving male students one by one to sit beside female students. Breaking down these barriers extended beyond just seating—we struggled at first to get students to interact with peers from different schools or outside their immediate social circles.

But through intentional strategies—mixed capstone groups, strategic lecture seating, and carefully designed classroom activities—we gradually pushed students to make more friends than the ones they came in with. The transformation was remarkable. By the program’s end, the same student who had protested my group assignments was beaming alongside his new teammates after their presentation. What began as enforced mixing had evolved into genuine connection and collaboration.

Merlin D’souza leads her section, “The Power of Storytelling.”

“You speak Konkani?!?”

This program holds a special place in my heart not only because we served students with local teachers-in-training, but also because of its profound personal connection. As a Goan whose parents grew up in similar schools, whose extended family—including two cousins who teach in school systems there—calls Goa home, this experience bridged my heritage with my present. Though my family emigrated to the US long ago, my parents instilled in me a deep appreciation for Goan culture, including speaking Konkani, the state language, at home.

Three days into the program, our teaching team noticed some students’ hesitancy to participate. When I approached these quiet students, they would confess their insecurity about their English skills. Yet when I encouraged them to try, they would reveal remarkably well-structured English—perhaps with mixed tenses, but their ideas came through clearly. What they lacked wasn’t ability, but confidence to make mistakes.

Their fear resonated with me, as I harbored similar anxieties about my Konkani. Despite my initial reluctance to speak it, worried about my imperfect accent and vocabulary, I decided to use this parallel to connect with them. Before beginning my lecture on storytelling in science and beyond, I stated in Konkani: “My name is Merlin. My Konkani is not the best, but the way you must practice English is the way I must practice Konkani.” I explained that I understood their intimidation—English might have been their third language—but growth requires pushing through discomfort.

My fellow teachers and I would remind the students it’s okay to make mistakes, we would help them out. Students began expressing themselves more freely and when they struggled to find an English word they knew in Konkani, I found joy with my fellow teachers in helping bridge that linguistic gap. Our teaching team helped create a space where language became a bridge rather than a barrier.

PSIL attendees listen to presentations.

Leaving Goa

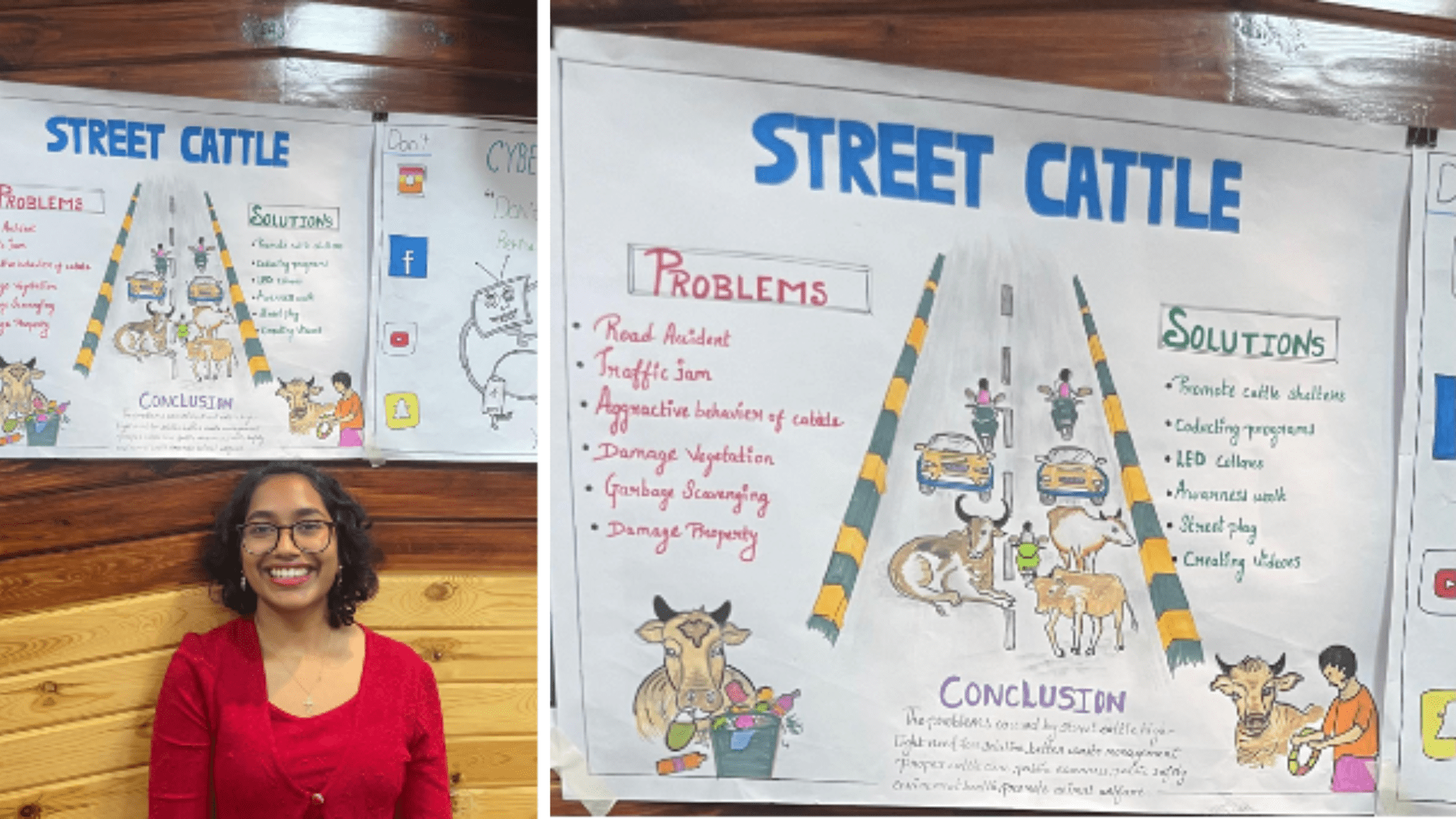

Saying goodbye to the students and the instructor fellows was hard. Learning and growing together was the beauty of this program. From the student’s capstones which were designed to be on problems they identified in the community and a solution to this program from their perspective, I learned about the danger of cattle on the street, unsustainable tourism, phone addiction. From the Goan teacher in training I learned how to balance being strict and fun, playing heads up, seven up before lunch and then getting them to focus after lunch. We had wonderful partners, the Goan Directorate of Higher education, in this program and I learned from their organization. They helped us source projectors and supplies. They bought the students sports equipment to play with and would help us succeed by supporting us from the sidelines.

What excites me most about PSIL is not just its immediate impact, but its lasting ripple effect across Goa. This isn’t a fleeting one-week workshop—it’s a sustained three-year commitment to developing student leaders. The program’s philosophy is simple: since students receive this valuable training at no cost, they’re asked to pay it forward by sharing their knowledge with others. As each cohort of PSIL graduates goes on to mentor and inspire their peers, we’re building a growing network of young leaders. This sustainable model of learn-and-teach ensures that PSIL’s impact will continue long after my fellow teachers and I leave beautiful Goa!

By Merlin D’souza ’25, Human Developmental and Regenerative Biology and Global Health and Health Policy

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subject and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mittal Institute, its staff, or its Steering Committee.