Kumbh Mela, one of the largest human gatherings on the planet, is a monumental Hindu pilgrimage and religious festival held in India every 12 years. An even more rare and significant version, the “Maha Kumbh Mela,” occurs just once every 144 years—the most recent taking place January to February 2025. Recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, the event draws tens of millions of devotees, necessitating the construction of vast temporary cities complete with infrastructure, sanitation systems, and large-scale crowd management.

In late February, Harvard Professors Tarun Khanna, Jorge Paulo Lemann Professor at the Harvard Business School, Diana L. Eck, Professor of Comparative Religion and Indian Studies, Emerita, and Tiona Zuzul, Assistant Professor of Business Administration, led a special discussion, “Insights from the World’s Largest Spiritual Gathering – Maha Kumbh,” organized by the Consulate General of India in New York. They reflected on their research and experiences from past and present Kumbh Melas. Read coverage on their talk from the Deccan Herald.

Tiona Zuzul, who also attended the recent Maha Kumbh Mela, shared a dispatch from her experience with the Mittal Institute, below.

Kumbh Field Notes

By Tiona Zuzul, Assistant Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School

In January 2025, I returned to the Maha Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj—a spiritual gathering that occurs every 12 years at the confluence of the Ganga, Yamuna, and the mythical Saraswati rivers, often described as the largest human congregation on Earth.

My first visit was in 2013, as a curious Ph.D student hoping to understand the emergence of order at this religious event and temporary mega-city. This time, I arrived as a professor at Harvard Business School, to explore what had changed and to write a case study on a company operating on-site. The 2025 gathering was a Maha Kumbh, a particularly auspicious version of the festival that occurs only once every 144 years. What I found was a Kumbh Mela that was at once the same—overwhelmingly crowded, deeply spiritual—but also transformed—bigger and more complex in every way.

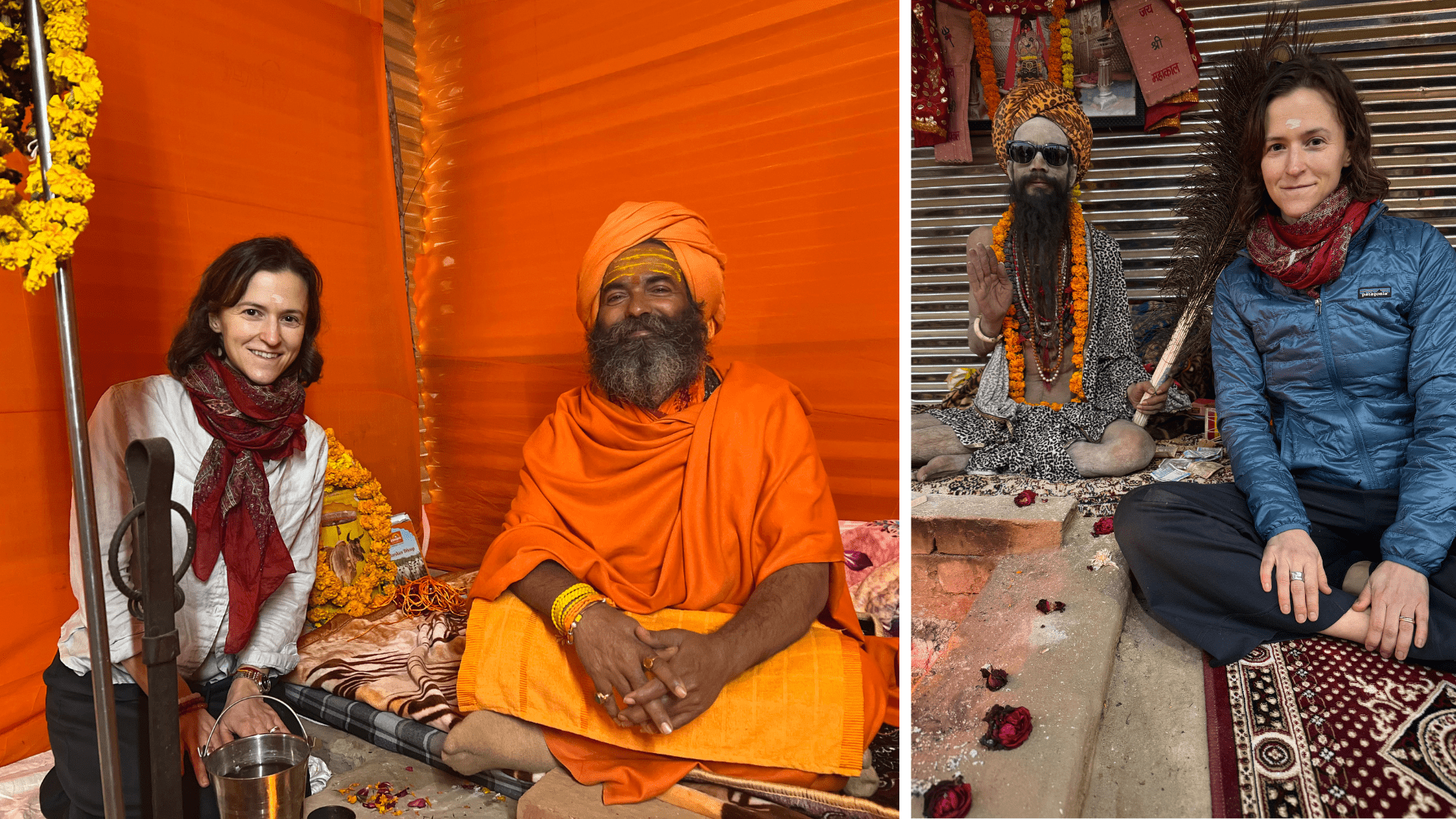

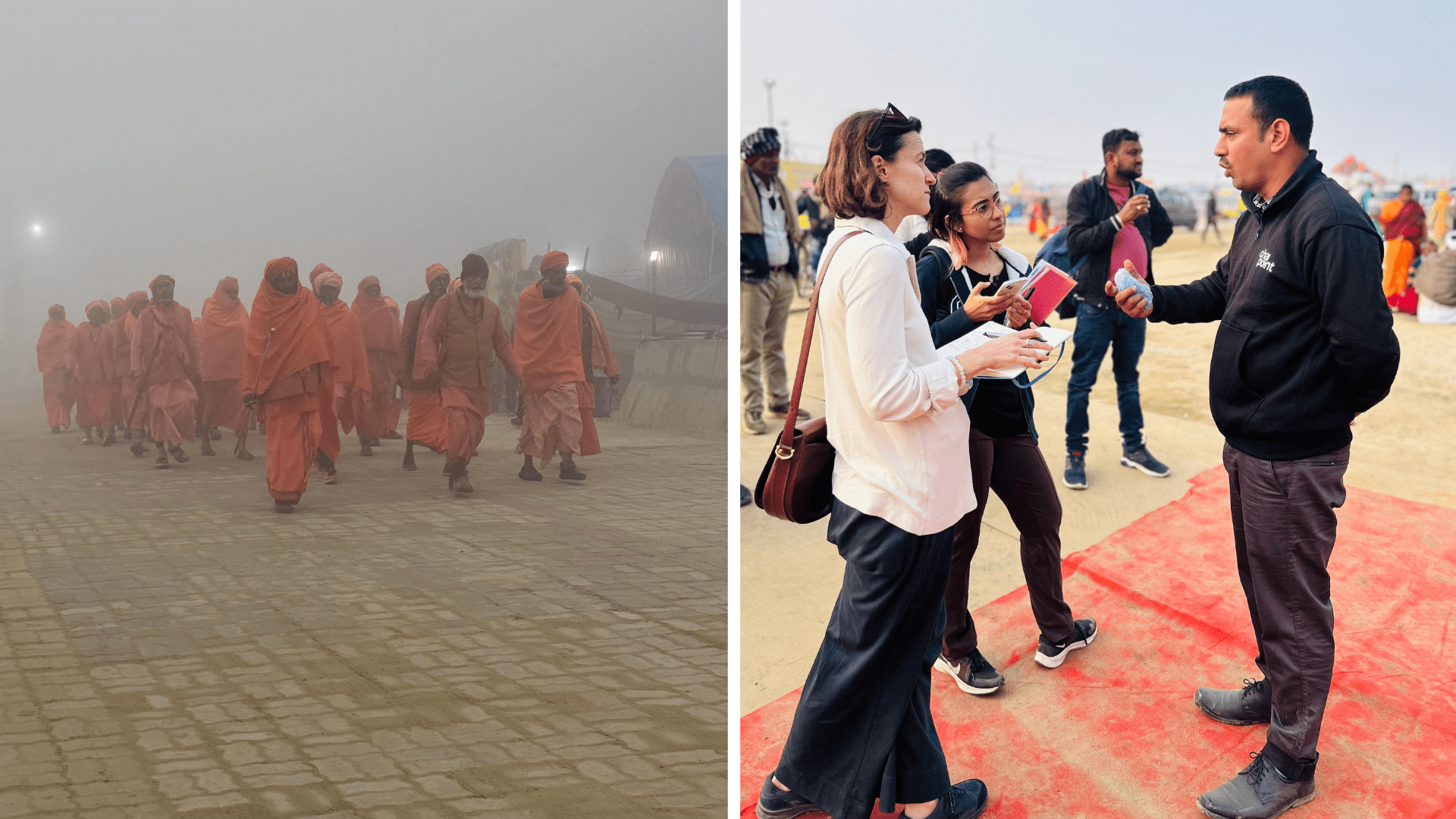

I spent my time at the Kumbh like many of its more than 500 million visitors—visiting the sangam (sacred confluence of rivers), wandering near akhadas (monastic orders of sadhus and ascetics, some of whom only appear in public during the Kumbh, that trace their lineages back centuries), receiving blessings—but also studying the evolving commercial landscape through field interviews.

Image, left: Evening in Juna akhada, one of the oldest and largest Hindu monastic orders in India; Image, right: Prof. Zuzul receives blessings.

Image, left: Sadhus walking at dawn to the sangam; Image, right: Prof. Zuzul conducts field interviews.

When I first visited the Kumbh in 2013, the vendor landscape was dominated by small-scale, often informal businesses: tea stalls, sellers of religious items, and food vendors. Many entrepreneurs miscalculated the scale of demand and struggled to recover the cost of their wholesale purchases. Despite the crowd size, profit was not guaranteed.

By 2025, the lines between mela and marketplace (the meaning of the word mela itself) had become harder to draw. Luxury tent accommodations, LED billboards, and major commercial brands were present. Many vendors—from international brands to local sellers—came to reach the staggering numbers of pilgrims. Others highlighted the Kumbh’s deeper spiritual purpose and described their role in devotional rather than purely commercial terms. A tea seller told me, “I am serving Maa Ganga,” framing his participation as seva—sacred service to the river and the pilgrims who come to her.

Prof. Zuzul in the Juna akhada.

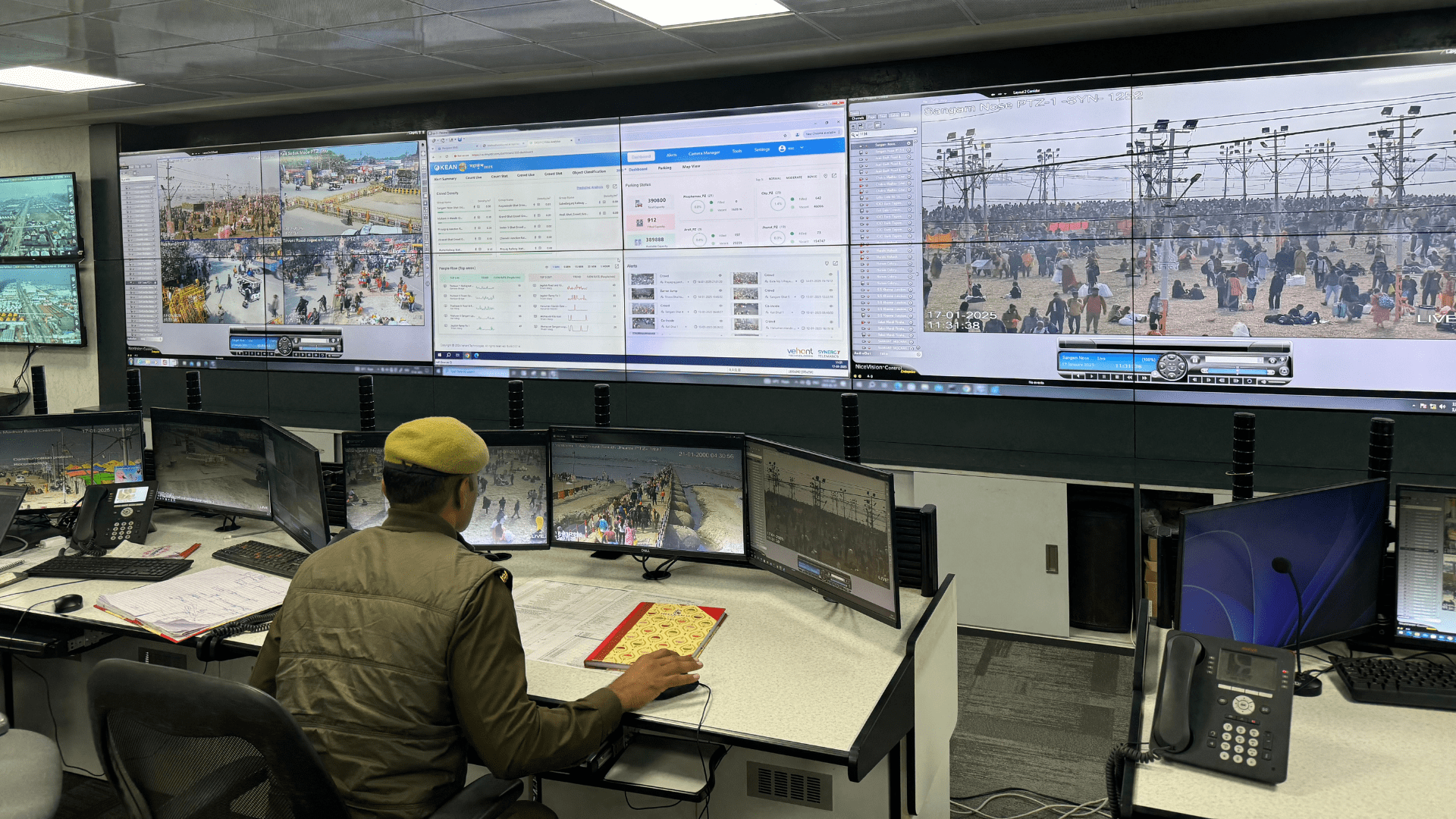

This Kumbh was also notable for the government’s implementation of advanced technologies, marking it as the first “Digital Maha Kumbh.” Artificial intelligence-powered surveillance and face-recognition systems, including over 2,700 AI-enabled cameras and drones, were deployed to monitor crowd density, predict surges, and prevent stampedes, reflecting a significant integration of technology into the traditional fabric of the Kumbh.

Prof. Zuzul visited the government control center.

As I explored the Kumbh, I reflected on a deeper tension that comes with this growth in business and technology: how much commercialization is too much? As the Kumbh continues to grow, its needs—for food, hygiene, security, and even basic services—necessitate the involvement of formal businesses and advanced technological solutions.

At the same time, this shift has sparked some concerns among spiritual leaders and participants. One sadhu lamented that many pilgrims now come “for YouTube videos and Instagram reels,” more interested in viral selfies than spiritual blessings.

This tension raises a question: what will the Kumbh Mela look like in the future—and what role should business and technology play in shaping it? The Kumbh has always been an extraordinary site of fluid identities and interactions: between old and new, between spiritual and commercial. As it evolves, the challenge will be to maintain the integrity of its purpose, even as it adapts to meet the needs of the modern world.

☆ The views represented herein are those of the interview subjects and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mittal Institute, its staff, or its Steering Committee.